The Lincoln Assassination: 150 Years Ago

Tuesday, April 7th, 2015by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent and researcher

[Warning – the following text contains some racist language in its original, historic context]

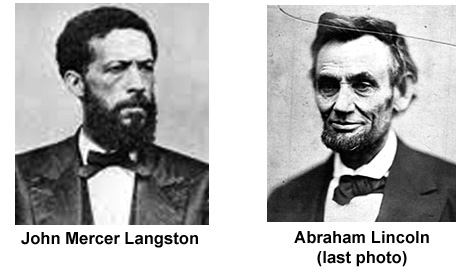

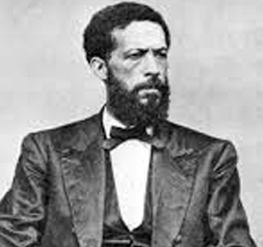

In the evening mist of April 11, 1865, Oberlin’s African American political leader, John Mercer Langston, stood among a crowd on the White House lawn and listened to the words of President Abraham Lincoln as he delivered, by candlelight from a second story window, a “grave and thrilling” speech. In it, Lincoln outlined his general philosophy for Reconstruction of the Union after four years of bloody civil war – a policy made imminent by the surrender two days earlier of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Acknowledging that his Reconstruction plan was a work in progress, Lincoln nevertheless defended it against critics who saw it as too lenient and conservative. “It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man,” the President confessed. “I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers. . .The colored man, too, in seeing all united for him, is inspired with vigilance, and energy, and daring, to the same end. Grant that he desires the elective franchise, will he not attain it sooner by saving the already advanced steps toward it, than by running backward over them?” It might not have been everything that Langston, an elected public official himself, hoped for. But in contrast to what any American President had ever said before, Lincoln’s words struck him as spoken “like a prophet, reminding one of the ancient Samuel as he called the people to witness his integrity.” Not far from where Langston stood, however, another listener had a very different reaction to Lincoln’s words. “That means nigger citizenship,” he hissed to his companions. And he added a vow: “That is the last speech he will ever give.” His name was John Wilkes Booth and, sadly, he was right about that. [1]

Meanwhile, back in Oberlin, the air was electric with the flush of victory and the promise of peace. A new term had just begun at Oberlin College, but students were finding it difficult to concentrate on their studies amid all the excitement of the recent news. First the Confederate capitol of Richmond, Virginia had fallen on April 2nd, then Lee’s army surrendered on April 9th. The long, bloody rebellion, like the Confederacy itself, was in its death throes. Oberlin College student Lucien Warner described the atmosphere:

“In the spring I returned to Oberlin to complete the last six months of my college course. We had hardly commenced our term when Petersburg and then Richmond fell, and the terrible four years’ war was ended. Victory rang through the nation, and people everywhere celebrated it in the most extravagant ways they could invent. Everything that could make a noise was called into commission, from horns and tin pans to old anvils. Such rejoicing comes to a nation but once in many generations. The whole land took on new light and hope, and we felt that we really were again one nation.” [2]

Ohio Governor John Brough proclaimed an official day of Thanksgiving to be observed on Good Friday, April 14th – the four year anniversary of the fall of Fort Sumter which had signaled the start of the Civil War. Oberlin went enthusiastically about the business of preparing for the celebration. When the appointed day arrived, there was something for everybody, as described by the Lorain County News:

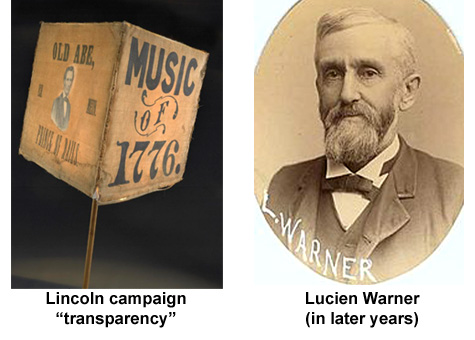

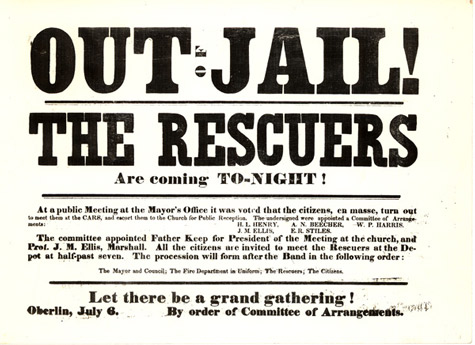

“The day was opened by the firing of a salute at 6 A.M. At half past ten the people gathered at the First Church to join in religious exercises and listen to addresses. Prof. [James H.] Fairchild, Prof. Morgan, and Principal [E. Henry] Fairchild each delivered brief, appropriate, and eloquent addresses, and at the close of the meeting a liberal collection was taken up for the Christian Commission. In the afternoon a prayer meeting was held in the First Church, and exercises were also held in the Second Church. The rejoicings were opened in the evening by the firing of a salute and the ringing of the bells. A general illumination of the College buildings, stores and private dwellings soon followed, and a procession representing beautiful designs, mottoes, transparencies of almost every description, moved through the principal streets, preceded by martial music, and brought up on Tappan Square, where patriotic speeches by citizens and students were listened to, fire-works and balloon ascensions were witnessed, and a huge bon-fire brilliantly lit up the entire square. Not an accident or disorderly act occurred to mar the spirit of the occasion, and although every one seemed to celebrate and rejoice with a hearty good will, there was observable a mingling of serious earnestness, and quiet joy, which is rarely seen on such occasions.” [3]

Lucien Warner described the festivities in a letter home to his mother:

“Last Friday was appointed by the Governor of this State for public Thanksgiving. All businesses were suspended and every one rejoiced as best he was able. In Cleveland every one rejoiced by getting drunk, but we remained sober and rejoiced. In the evening almost every house, tree and door-yard was illuminated, and flags, banners and transparencies were without number. There were about ten thousand candles burning all at once in the illumination.” [4]

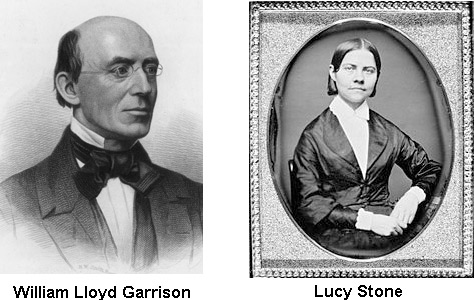

Oberlin went to bed that night and slept in a state of blissful peace.

But while Oberlinites slept, the telegraph did not:

Washington – April 15, 12:30 A.M. The President was shot at a theatre to-night and is perhaps mortally wounded.

——————————————————————–

Washington – April 15, 3:00 A.M. The President is not expected to live through the night. He was shot at a theatre. Secretary Seward was also assassinated. There were no arteries cut. Particulars soon.

——————————————————————–

WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, April 15

To Maj Gen Dix;

Abraham Lincoln died this morning at twenty-two minutes after seven o’clock.

EDWIN M. STANTON, Sec’y of War [5]

——————————————————————–

There was no daily newspaper published in Oberlin at that time, so the awful tidings traveled by word of mouth the following morning. The sudden shock of the tragic news, in contrast to the jubilation of the night before, was still vividly recalled by Reverend Roselle T. Cross, then an Oberlin College student, 28 years later:

“Who that was present can forget the rejoicing of April 14th? Who can forget the illuminations of that night, or the great bonfire in Tappan Square, around which four thousand people were gathered. And who can forget the awful shock of the next morning when news came of Lincoln’s assassination; all day it rained; recitations were suspended. All day we walked the streets aimlessly, scarcely recognizing our friends when we met them. All day long the college bell tolled.” [6]

The Lorain County News described the mood in its next issue, published the following Wednesday:

“But who will attempt to describe our feelings on the reception of the crushing news early on the following day? At first it seemed incredible. The sudden transition from overflowing joy, and praise and gratitude to God, to the overwhelming grief which the terrible tidings brought upon us, was too much for the great heart of the people to bear, and all sank beneath it like a crushed reed. The stars and stripes were lowered half-mast, the chapel bell tolled solemnly and mournfully throughout the long, weary day, recitations were suspended in the Institution, crowds hurried to the [train] depot, to get a sight of the morning paper, business was nearly suspended, the land was overshadowed with dark and weeping clouds, and all nature seemed to mourn.” [7]

Lucien Warner, who had seen President Lincoln in person the year before while serving a 100 day enlistment in the Union army defenses of Washington, D.C., learned the news at the end of his morning recitation:

“The next morning at nine o’clock we received the sad intelligence of the assassination of President Lincoln. It was as though a clap of thunder had stunned every person. The news was brought to our class at the close of a recitation. For nearly five minutes we sat motionless, forgetting that the class had been dismissed. I have loved other public men, but the death of no one could have affected me like that of President Lincoln. Ever since I looked upon his honest, genial countenance I have loved him like an intimate friend; and so I suppose did every loyal man. I think there were but few in this town but that shed tears on that day. Further study was out of the question.” [8]

Throughout the day, as the chapel bell tolled and the students “put on crepe”, details trickled in about the assassinations. The President had been shot in the back of the head by an actor named John Wilkes Booth. Secretary of State William Seward had been the victim of a savage knife attack at approximately the same time by another assassin – one of Booth’s companions at Lincoln’s final speech, it would turn out. Later that Saturday morning the telegraph brought news that Secretary Seward had also died. It wouldn’t be until Monday that it was learned that Seward had survived, to the relief of “the overburdened public mind”. [9]

The assassinations would be the main topic of two sermons delivered the next day, Easter Sunday, by Reverend Charles G. Finney at First Church. Finney was one of those who believed that “Mr. Lincoln was a man so intensely kind & accommodating that many of us felt that he might be induced to leave the power of the great slave holders unbroken, by too lenient an exercise of the pardoning power.” And now he told his congregation: “We must show the world that rebellion is a fearful, terrible thing. The President was an amiable man, tender, kind-hearted, but perhaps he stood in God’s way of dealing with the Rebels just as they ought to be dealt with for the good of the nation, and for the good of humanity.” [10]

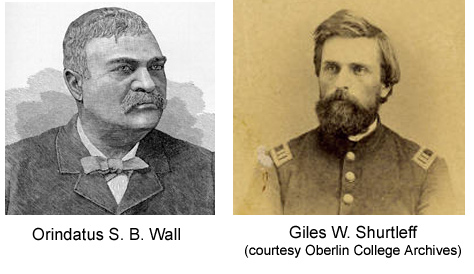

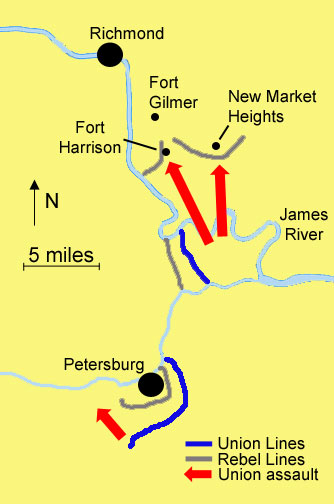

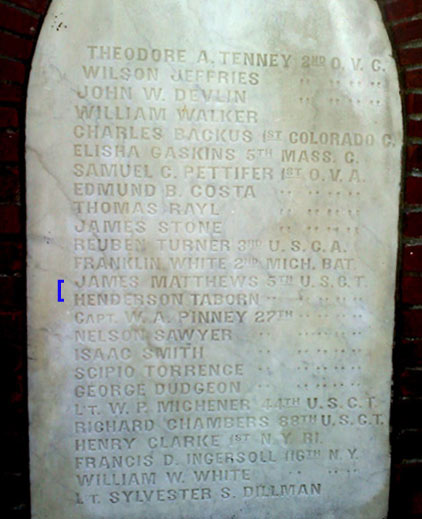

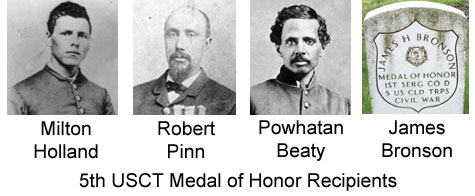

John Mercer Langston was still in Washington, D.C. when John Wilkes Booth made good his vow – three nights after Lincoln delivered that fateful speech. Langston had gone there before the surrender of Robert E. Lee with a bold proposal (for that era) – requesting a colonel’s commission and the command of a combat regiment of United States Colored Troops (USCT). Just months earlier, Sergeant Milton Holland, one of several men Langston had recruited into the 5th USCT infantry regiment, had been denied a promotion to captain because the War Department was reluctant to appoint African Americans as combat officers. (See my Battle of New Market Heights blog.) But with the hearty endorsement of Ohio abolitionist General James A. Garfield (who himself would be assassinated as President sixteen years later), Langston received an encouraging reception from Secretary of War Stanton, and Langston and Garfield left the interview “with the belief firmly settled in their minds” that Langston’s proposal “would receive the sanction and approval of the authorities.” With the surrender of Lee, however, the army immediately began to scale down, and Langston noted that “the department very properly concluded not to adopt the measure”. On the heels of this came what Langston called “the horror of horrors” – “the assassination of the immortal Abraham Lincoln.” While it was no secret among abolitionists that Lincoln himself shared some of the racial prejudices of his day, Langston saw him as “a statesman without an equal; a leader, as grand in the immense proportions of his individuality as Moses himself; an emancipator of a race.” [11]

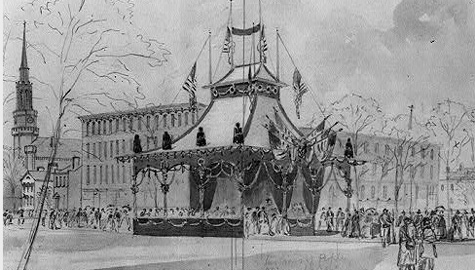

Another Oberlin political leader, James Monroe, didn’t learn of the assassinations until more than a month after the fact, having been appointed by Lincoln as U.S. consul to Rio de Janeiro. When the news finally reached Brazil of the “monstrous crimes”, Monroe declared: “Our strong men wept, and every one felt that he had experienced a great personal calamity.” Back in 1861, Monroe had had the honor of accompanying President-elect Lincoln on part of his railroad journey from his hometown of Springfield, Illinois to his inauguration in Washington, D.C. But by the time Monroe learned of Lincoln’s death, the Lincoln funeral train had already retraced the inaugural route back to Springfield, including a stop in Cleveland where thousands of mourners paid their final respects. Among those mourners were some from Oberlin, including Oberlin College student John G. Fraser, who recorded in his diary: [12]

“The crowd was the largest I ever saw and by far the most quiet and orderly. The very skies seemed to be weeping for the good man’s fall. I looked upon his face three times. It has a quiet, peaceful look upon it, as though he were at peace with his God, himself and all the world. How could an assassin have the heart to kill such a man?”

Lincoln funeral reception – Cleveland

Some in that mournful throng may have recalled back to the inaugural train journey of four years earlier and a brief, impromptu, perhaps prophetic speech President-elect Lincoln delivered in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, where the Declaration of Independence was signed and the nation was born. But when Lincoln spoke there in 1861 the nation’s survival seemed uncertain, with several slaveholding states having declared themselves seceded from the Union because, as their own newly elected President, Jefferson Davis, explained it, “the sacred Declaration of Independence has been invoked to maintain the position of the equality of the races.” [13] Speaking on Washington’s birthday, with the prospect of civil war looming and rumors of assassination plots abounding, President-elect Lincoln re-affirmed his commitment to that “sacred Declaration”: [14]

“I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence… which gave liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but, I hope, to the world, for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weight would be lifted from the shoulders of all men. This is a sentiment embodied in the Declaration of Independence. Now, my friends, can this country be saved upon that basis? If it can, I will consider myself one of the happiest men in the world, if I can help to save it. If it cannot be saved upon that principle, it will be truly awful. But if this country cannot be saved without giving up that principle, I was about to say I would rather be assassinated on this spot than surrender it…

My friends, this is wholly an unexpected speech… I may, therefore, have said something indiscreet. I have said nothing but what I am willing to live by and, if it be the pleasure of Almighty God, die by.” – Abraham Lincoln, February 22, 1861

SOURCES CONSULTED:

“Oberlin Local: The Thanksgiving and Celebration”, Lorain County News, April 19, 1865, p. 2

John Mercer Langston, From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol

David Herbert Donald, Lincoln

Lucien Calvin Warner, Personal Memoirs of Lucien Calvin Warner

Robert Samuel Fletcher, A History of Oberlin College From its Foundation through the Civil War, volume 2

“Last Public Address”, Abraham Lincoln Online

“Assassination of President Lincoln and Secretary Seward”, Lorain County News, April 19, 1865, p. 2

Rev R. T. Cross, “The Fourth Decade”, The Oberlin Jubilee 1833-1883

Charles G. Finney to James Barlow, June 22, 1865, The Gospel Truth

“Address in Independence Hall”, Abraham Lincoln Online

“Jefferson Davis’ Farewell Address”, The Papers of Jefferson Davis, Senate Chamber, U.S. Capitol, January 21, 1861

“The Great Sorrow”, Lorain County News, April 19, 1865, p. 2

James Monroe, Oberlin Thursday Lectures, Addresses, and Essays

“Building Erected for the Reception of the Body of the President at Cleveland”, Library of Congress

“Lincoln Parade Transparency, 1860”, Smithsonian: The National Museum of American History

Catherine M. Rokicky, James Monroe: Oberlin’s Christian Statesman and Reformer, 1821-1898

William Cheek and Aimee Lee Cheek, John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom: 1829-1865

Jacob Henry Studer, Columbus, Ohio: Its History, Resources and Progress

James H. Fairchild, Oberlin: The Colony and the College, 1833-1883

General Catalogue of Oberlin College: 1833- 1908

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Langston, pp. 220-221; “Last Public“; Donald, pp. 581-588

[2] Warner, p. 45

[3] “Oberlin Local”

[4] Warner, p. 45

[5] “Assassination”

[6] Cross, p. 220

[7] “Oberlin Local”

[8] Warner, pp. 45-46

[9] Fletcher, p. 883; “The Great Sorrow”

[10] Charles G. Finney; Fletcher, p. 883

[11] Langston, pp. 219-223

[12] Monroe, pp. 206-207; Rokicky, pp. 65-66; Fletcher, pp. 883-884

[13] “Jefferson Davis’ Farewell Address”

[14] “Address in Independence Hall”