Juneteenth – the “extinction” of legalized slavery in America

Friday, June 12th, 2015by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent, researcher and trustee

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the first “Juneteenth” – June 19, 1865 – a day which has come to commemorate the end of slavery in the United States. Since Juneteenth is such an important day in modern Oberlin, and the fight against slavery was such an important part of Oberlin’s early history, I thought I’d take the opportunity to write a blog describing how American slavery ended, how Oberlin reacted to it, and why Juneteenth has been chosen as the day to celebrate it. None of it was as straightforward as one might think.

Most people are aware that American slavery was ended by the Civil War, and that specifically President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had something to do with it. But the actual demise of slavery was in fact a complicated process, as might be expected of an institution that had become so deeply ingrained in the American social, political and economic landscape throughout the first “four score and 7 years” of this nation’s existence.

When President Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4, 1861, seven slaveholding states had already declared themselves seceded from the Union and were in the process of arming themselves for potential war. “One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended,” Lincoln said in his inaugural address, “while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.” And he meant it. Three months earlier, when slaveholding states began to call for secession conventions in response to Lincoln’s election, President-elect Lincoln told a colleague in a private dispatch: “Entertain no proposition for a compromise in regard to the extension of slavery… Have none of it. The tug has to come & better now than later.” But while Lincoln always maintained that stopping the expansion of slavery would put it on “the course of ultimate extinction”, he also reassured slaveholders in that same inaugural address that “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” [1]

Most abolitionists and Oberlinites concurred. Initially, that is. But surely, they thought, when the Confederate states opened fire on Fort Sumter in April, 1861, President Lincoln would use the opportunity to eradicate slavery forever. After all, former President John Quincy Adams, who as a Constitutional lawyer successfully argued the Amistad case before the U.S. Supreme Court, had told Congress twenty years earlier that “under a state of actual invasion and of actual war… not only the President of the United States but the commander of the army has power to order the universal emancipation of the slaves.” But even as Lincoln called up troops to put down the rebellion, he held fast to both his promises – he would not compromise on the extension of slavery into new territory, but he also would not interfere with slavery in the states where it already existed. In fact as combat operations began, he censured those military commanders who took it upon themselves to emancipate the slaves in their jurisdiction, and supported military commanders who returned escaped slaves to their owners. More than a year into the war, Lincoln would still insist that his “paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union”, and that although his “personal wish” remained “that all men every where could be free”, he would use his war powers to free the slaves only insofar as he believed it would “save the Union”. [2]

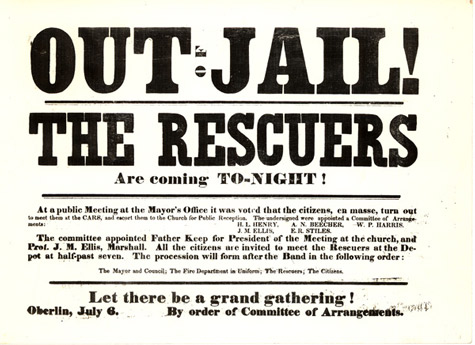

Perplexed on how to proceed, the citizens of Oberlin called a series of public meetings during commencement week, in August, 1861, to discuss the situation. The meetings drew not only local dignitaries, but such nationally recognized figures as the renowned abolitionist Reverend Edward Beecher (brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe) from Massachusetts, and U.S. Representative James Ashley from Toledo. (Ashley was himself a former Underground Railroad conductor who was portrayed, not altogether flatteringly, in Stephen Spielberg’s recent movie “Lincoln”.) Speaking just weeks after Union forces had suffered a major, humiliating defeat in Virginia, Representative Ashley told his Oberlin audience:

“I am now on my return homewards from Washington. I saw President Lincoln but the day before I left. He said to me – Can you tell me why it is that one Secessionist [soldier] is equal to five Union men? I said, Yes. The reason is that the Secessionist has an idea; the Union men have not. The former knows what he works and fights for. The latter don’t know. They must save Slavery and yet must fight it; and in this everlasting perplexity and conflict of aims and interests, they cannot have energy, or will…

Now, friends, if you will speak out, and if the people of the Great West will speak out, our rulers will obey. And for myself I am not willing to give such favors to rebels as the policy of our Government thus far seems to accord them.”

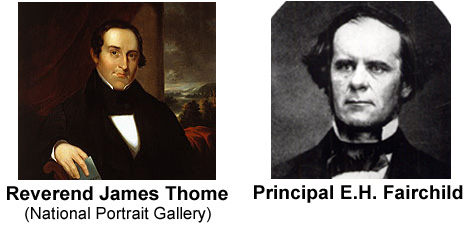

Reverend Beecher resolved that “By virtue of the present treason and war, we have a legal right to strike Slavery down”, and “If this is not done, a dark mist of uncertainty hangs over the issue of this war.” These sentiments resonated with the locals. Cleveland Reverend James Thome (a former Oberlin College Professor and Lane Rebel) proclaimed, “We who have spoken out all along thus far, ought to speak out now. Our Government needs and perhaps desires just this expression from us. If ever there was a time when courage and unswerving boldness were in season, that time is now.”

Edward H. Fairchild, Principal of the Oberlin College Preparatory Department, took it a step further. Not only should the slaves be freed, they should be armed and allowed to fight: “Let the blacks, bond and free, be marshalled for this contest, and come up to strike for Freedom, and to smite down this rebellion. When armed and disciplined, let them sweep the Gulf States, take possession, and hold the country. It is legitimately theirs.” And according to the Oberlin Evangelist, “All agreed that, through a specially kind Providence, Slavery had put itself into a position where it may be smitten down, and that it is in the highest degree wise for the Federal Government to exercise this war power as fast as it can be done to purpose.” [3]

But it would be more than a year later before Lincoln was finally ready to act. And even then it wouldn’t be the “universal emancipation” that John Quincy Adams had envisioned two decades earlier. Lincoln insisted that the Constitution only gave him authority to free the slaves in regions that were in rebellion, and thus his Emancipation Proclamation, which went into effect on January 1, 1863, freed only those “persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States.” Fully aware that slaveholders in those rebellious regions would not feel the least bit bound by the President’s proclamation, some abolitionists cried foul – insisting that the proclamation didn’t free any slaves at all. But in Oberlin it was generally cheered. The Proclamation in fact freed thousands of slaves immediately, some of them right in Oberlin, who had escaped from the rebel states and had ever since lived in constant apprehension of recapture and return to slavery. And it was understood that with each advance of Union arms many more slaves would be freed, and many of them in turn, would “be marshalled for this contest, and come up to strike for Freedom” themselves, as Principal Fairchild had advocated more than a year earlier. And so the Oberlin Evangelist jubilantly proclaimed: [4]

“We shall account this proclamation as the great and glorious decision. It fixes a policy. It is a mighty word for freedom. Its echoes will gladden four millions of hearts where little joy has found place for many generations. We hope the watchword as the tidings flash from one plantation to another all the way from the Potomac to the Rio Grande, will be Pray and wait. The God of the oppressed is surely coming!”

And that’s exactly how it happened. As Union armed forces made their slow but steady advance into the Confederate interior, the tidings did indeed flash from one plantation to another. In 1864 the tidings were carried to coastal North Carolina and Virginia, as the 5th United States Colored Troops (USCT), a regiment of “blacks, bond and free” with a strong Oberlin presence, conducted raids into rebel territory, freeing slaves as it went. (See my Battle of New Market Heights blog.) Hundreds of miles away the tidings flashed to Eliza Wallace, in Natchez, Mississippi, who with her three children was helped on the road to Oberlin and freedom by Oberlin resident and alumnus, Chaplain Sela Wright of the 70th United States Colored Infantry. Nobody knows how many thousands of slaves were freed between Natchez and the Virginia coast, but it’s estimated that 130,000 of them served in the United States army. And ultimately, after much praying and waiting, the tidings did indeed make it all the way to the Rio Grande, but not until weeks after Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox, President Lincoln had been assassinated, and many considered the war to be over. And so it was that on June 19, 1865 Union General Gordon Granger landed at Galveston, Texas with a proclamation that “all slaves are free” and with the military power to back it up. The promise of the Emancipation Proclamation was now complete. [5]

Reverend Sela Wright, in later years

(courtesy Oberlin College Archives)

But wait! We seem to be forgetting something. Recall that the Emancipation Proclamation only freed those slaves in regions “in rebellion against the United States”. What about the hundreds of thousands of slaves held in regions where the rebellion had already been suppressed, or slaveholding states which had remained loyal right from the start, like Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland and Delaware? Well, the Lincoln Administration didn’t forget about them either. In fact it employed a carrot and stick approach to entice these regions to abolish slavery voluntarily, which most of them did by the time General Granger landed in Galveston. And for the last stubborn holdouts – Kentucky and Delaware – the Lincoln Administration had also been using a carrot and stick approach to pass a Constitutional Amendment, originally introduced into Congress by none other than Representative James Ashley (mentioned above), that would ban slavery nationwide and forever. That amendment was finally ratified on December 18, 1865, becoming the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, making institutional, legalized slavery extinct everywhere in the United States of America.

So why do we celebrate June 19, 1865, a date that really only affected the slaves in Galveston, Texas? Probably for the simple reason that they and their descendants kept the memory alive, year after year after year. Today we might be more inclined to see January 1 (the date the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect) or December 18 (the date the 13th Amendment was ratified) as more appropriate for a national celebration. But the vast majority of slaves were freed between those two events, and with a bloody Civil War and a strife-filled Reconstruction in progress, the freed men and women had all they could do to make the difficult transition to freedom, without trying to organize a national day of commemoration. It wasn’t until the civil rights era of the 20th century that Galveston’s celebration garnered national attention, and the idea spread slowly across the country. In 2004 the City of Oberlin officially joined the throng by designating “Juneteenth, the Saturday in June that falls between the 13th and 19th of June each year, as an Officially Recognized day of Commemoration and Celebration.” [6]

So please join us in celebrating the 150th anniversary of Juneteenth this Saturday, June 13th, in Oberlin. Enjoy the many cultural festivities, stop by the Oberlin Heritage Center’s booth on Tappan Square, perhaps even sign up for one of our historic tours. But as you’re enjoying the food, music and fun, remember too the millions of Americans who endured the bitter hopelessness of this awful institution, and remember the hundreds of thousands of Americans, black and white, who fought for freedom – some, like Gordon Granger, Sela Wright and the men of the 5th USCT, who freed slaves outright, and others who fought to preserve a Union that would finally bring slavery to its “ultimate extinction”. And remember too that while institutional slavery is indeed extinct, the racial prejudices and mistrust that propagated it and were perpetuated by it are not. But that’s our battle.

Happy Juneteenth (and go Cavs)!

SOURCES CONSULTED:

“Discussion on Slavery and the War”, The Oberlin Evangelist, Sept. 11, 1861, p. 4

“Legal Notice of Coming Emancipation”, The Oberlin Evangelist, Oct. 8, 1862, p. 3

“The Emancipation Proclamation”, National Archives & Records Administration

“History of Juneteenth“, Juneteenth.com

Oberlin Resolution (R01-06-CMS), Oberlin Juneteenth, Inc.

Abraham Lincoln, First inaugural address, March 4, 1861

Abraham Lincoln to William Kellogg, December 11, 1860, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol 4

Abraham Lincoln reply to Horace Greeley, August 22, 1861, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol 5

Worthington Chauncey Ford and Charles Francis Adams, John Quincy Adams: His Connection with the Monroe Doctrine (1823)

Oberlin News, June 12, 1893

Paul Finkelman, Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895

Abraham Lincoln, “Mr. Lincoln’s Reply”, Third Joint Debate at Jonesboro, IL, Sept 15, 1858

“Wright, Sela G.”, Soldiers and Sailors Database – The Civil War, National Park Service

William E. Bigglestone, They Stopped in Oberlin

General catalogue of Oberlin college, 1833 [-] 1908, Oberlin College Archives

FOOTNOTES:

[1] First inaugural address; Kellogg; Jonesboro

[2] Ford, Adams, p. 77; Greeley

[3] “Discussion”

[4] Emancipation Proclamation; “Legal Notice”

[5] Oberlin News; “Wright“; General catalogue; Finkelman, p. 394; “History”

[6] “History“, Oberlin Resolution