1930 Drought: The Most Critical Situation in Oberlin’s Waterworks History

Tuesday, September 14th, 2021By Zenobia Calhoun, 2021 Summer OHC Volunteer

A long drought in 1930 tested Oberlinians’ energy and strength along with millions around the nation. It decimated crops and threatened Oberlin’s water supply: “The water shortage really was a serious condition—more serious than most people were inclined to believe,” said Superintendent of the Maintenance Department Doren Lyon in 1931.[1] The drought also created other potential problems, like disease outbreaks and worse fires. The drought was statewide and nationwide, as the results of the dust bowl show. Before 1930, the northern areas of Fulton, Lucas, Ottawa, Erie, and Lorain counties were usually the driest, each having 33 inches of rain or less for the whole year, with the whole state averaging 38.25 inches. However, in 1930, the whole state averaged just 27 inches of rain.

Data from Straszheim, Robert E, and Falconor, J I. “The Drought in 1930.” Mimeograph Bulletin 37 [of the Department of Rural Economics at Ohio State University] (April 1931).

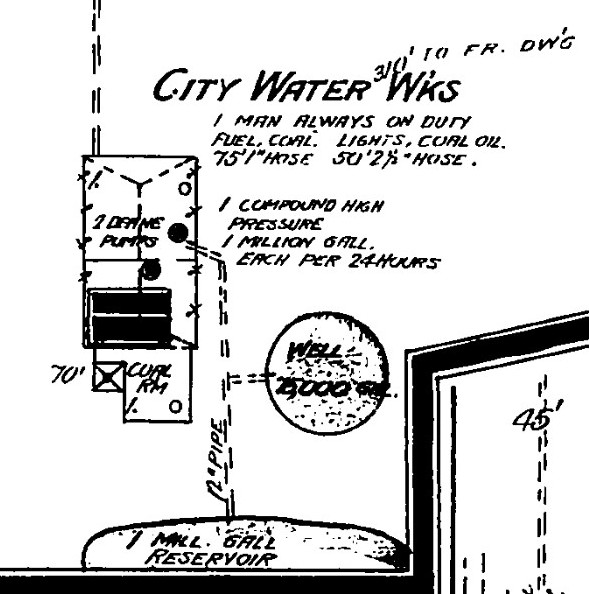

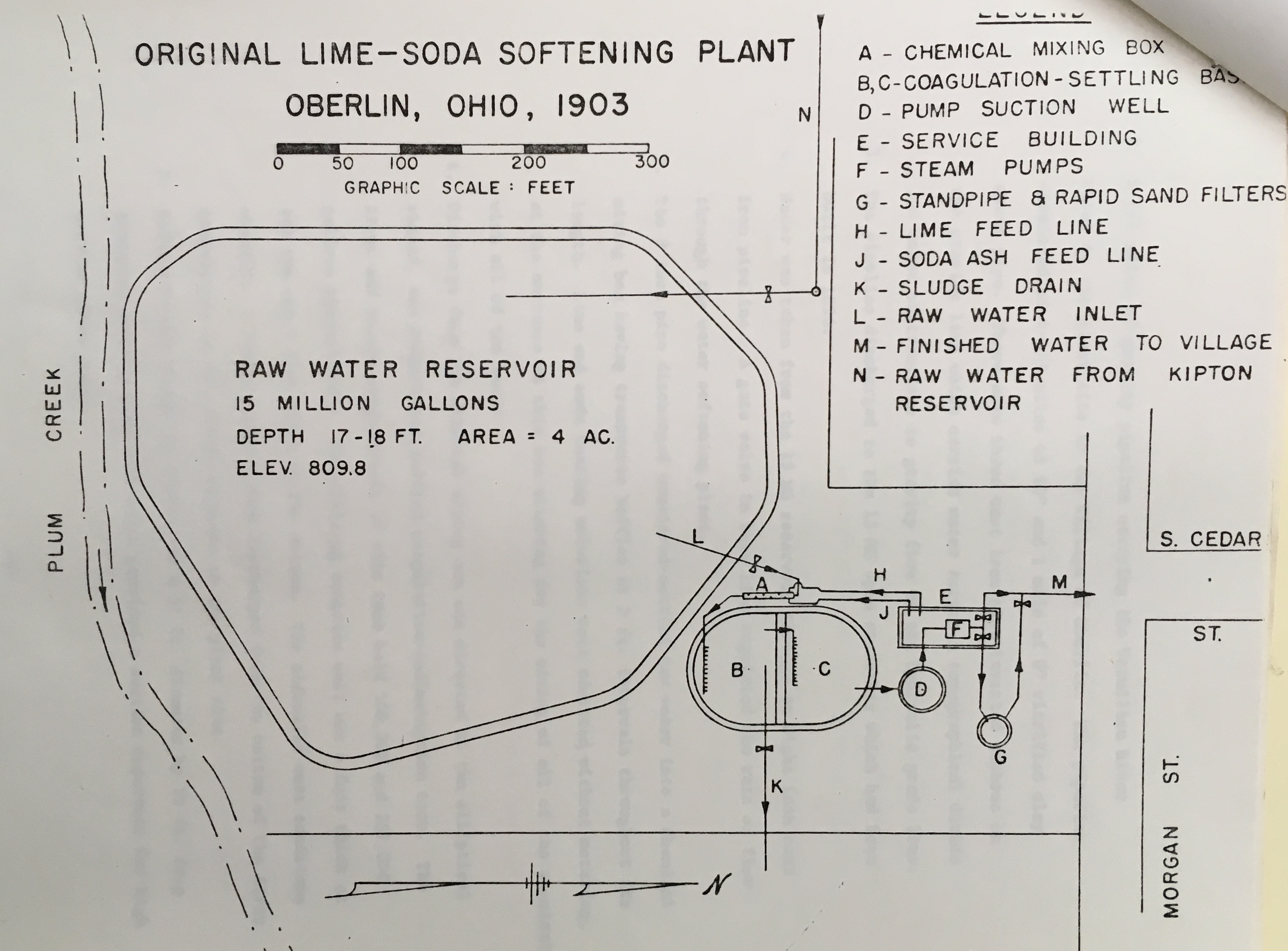

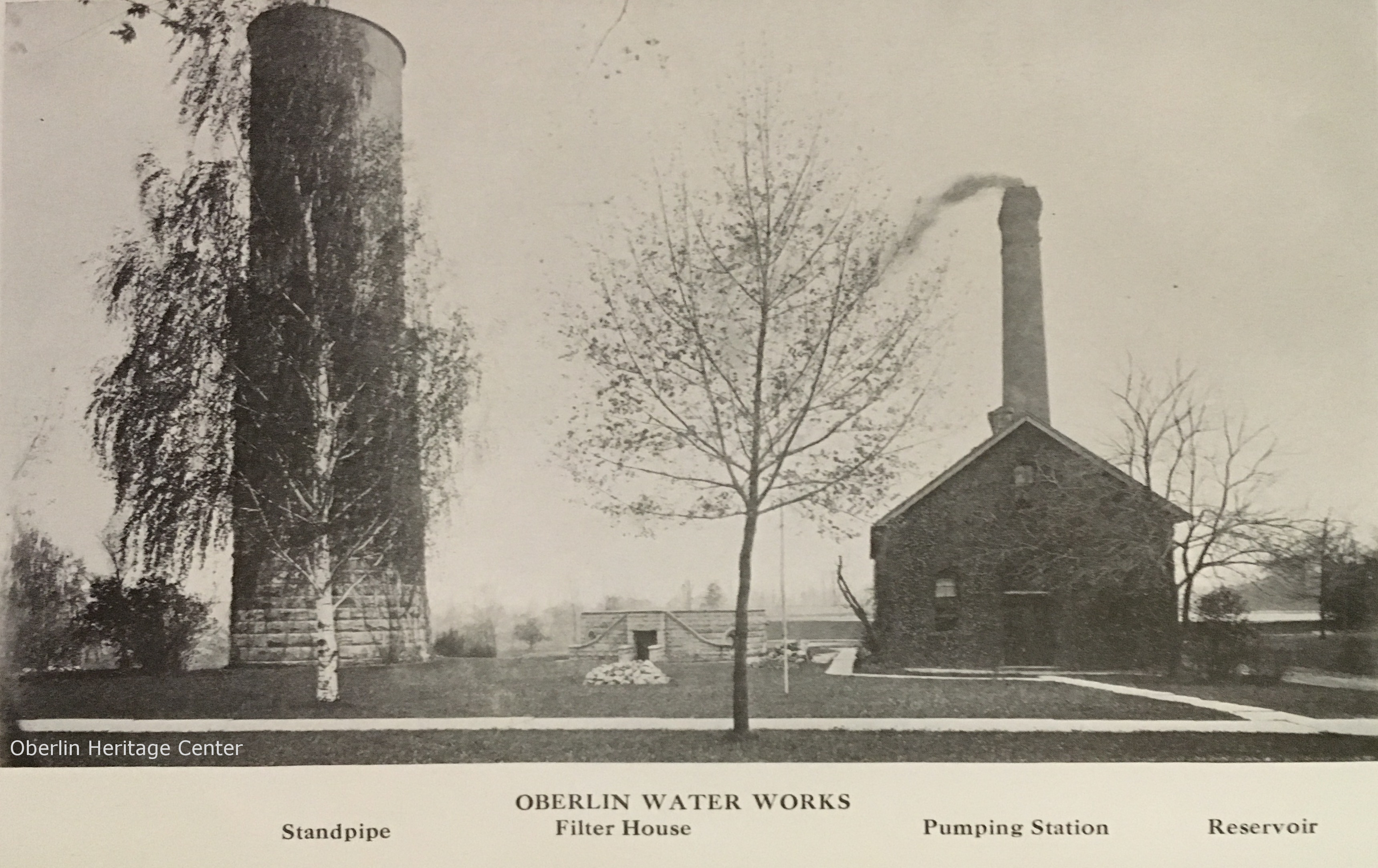

The main concern of water management in 1930 was having enough safe drinking water for everyone in Oberlin. Other concerns included saving the crops of the year and fire and disease outbreaks. At the beginning of 1930, Oberlin’s water supply was the Vermilion River in South Kipton. By July, the drought was already well-underway and the Oberlin News-Tribune noted that city officials asked citizens not to use water for “unnecessary purposes”, which included washing cars, watering gardens, and maintenance of the golf course.[2] At that time, there was enough water for another 30 days of regular use, which worried the city council as August is usually a dry month. Delaying the start of the college year was also considered as a mitigation strategy. Waterworks Superintendent Harry V. “Vic” Zahm also reported that due to the record-setting high temperatures there was a 25% increase in the amount of water used in comparison to the previous July, mainly in attempts to cool off. In Cleveland, a new high of 97 degrees was recorded for July.

Sears, L A. “Notice To Water Users.” Oberlin News-Tribune. August 7, 1930.

The second major concern was agriculture, both livestock and crops. The Oberlin News-Tribune reported on July 31 that the early corn was a failure and that late corn, potatoes, berries, and small fruit were soon to follow, and that even “should weather conditions become favorable, the crop will be way below the average.” On August 7, it was reported that farmers had been hauling water for their stock, burned pastures, and had no hope for the corn crop.

Usually, drought fears are alleviated by fall; however, in 1930 they remained. A little rain fell in September, but not enough to eradicate the fears of the Oberlin City Council and City Manager Leon Sears. The Oberlin News-Tribune noted on September 11 that there was still “real need of conservation wherever possible” and that the Elyria paper with the heading “No Shortage of Water at Oberlin” was “entirely misleading”. It was decided the college would start on schedule, though village officials worried about the new strain on the water supply. The article went on to explain how the Oberlin Water Department had bought a booster pump to move water from the Morgan Street reservoir to the settling basins, and that the watershed in Kipton now provided a trickle, rather than a stream, with outtake far exceeding intake.

On September 25, the Oberlin News-Tribune noted that there was enough water in the reservoir for 40 days of use. City Manager Sears believed that the worst fears were over and with continued caution the town would get along until normal weather conditions return. There had been light showers, but no heavy rains. The Kipton reservoir and watershed seemed much better off than earlier in the same month, with around 1/3 of the daily consumption running to the reservoir, but the mood was hopeful and city officials believed water restrictions could be lifted after several heavy rains.

In early November 1930, water restraints were still present. The average daily consumption of water was 262,000 gallons, with much less coming down the conduit from Kipton. The autumn rain had not been enough to stop the daily lowering of the reservoir. Luckily, City Manager Sears and City Council had been searching for a new water source and they found one. The Nichols stone quarry located east of Kipton had a large volume of water they pumped out daily which had previously been being wasted. The company agreed to turn the water into a line connected to Oberlin’s water conduit, adding 50,000 gallons of water to Oberlin’s daily water supply. The water, being from under a quarry, was also softer and purer then the regular supply and required less chemical treatment. Oberlin citizens were also working to use less water. The daily average of the week of November 13 was 230,000 gallons. By extreme economizing, city officials believed the town could cut down to 225,000 gallons daily.

It was found that college students were also using less water than in the beginning of the semester. However, one dorm might have been an exception. A story was received at the Oberlin News-Tribune from a college student: the inmates of her dorm were homesick and had been trying to use as much water as possible so that they could go home [3] (assuming that if the drought situation become more dire, the college would be obliged to take a break) [4]. However, besides this stand-out anecdote, most Oberlin residents and college students alike worked to ration their water throughout the drought.

Unfortunately, droughts can have other negative effects besides loss of drinking water. The Ohio Department of Health informed county and local officials that the current weather could result in more outbreaks of typhoid fever due to people seeking new, less safe water supplies, and the eventual rain picking up many pollutants and making more water supplies unsafe. The Lorain County Health Commissioner, Dr. Barrett, recommended immunization against typhoid fever for all who were drinking even possibly unsafe water.[5] Surveys by the health department found that 2/3 of dug wells at the time were not fully protected against pollution, making them vulnerable to typhoid and other germs, especially in the expected first heavy rains.[6]

In August and September, fire precautions were limited to help conserve water. This meant that there was no longer a waiting water supply, and, if there had been a large fire in the year, destruction would have been extreme. Thankfully, there was not. However, a local fire department noted in early 1931 that there was a significant increase in the number of fires in 1930 in comparison to past years, causing $2,760 worth of damage, or around $44,000 in today’s money.

By March 1931, all water supply fears had been reprieved and there was more than enough rain to last until spring. However, the fear of the previous year was still felt. Jacob Berg, an Oberlin resident who kept a diary recording the weather every day, found that the year 1930 was the driest in 60 years, [7] while Superintendent Lyon revealed that in October in 1930 there was a water supply for just 30 days, and that the situation was “the most critical that has ever been in the history of the Oberlin waterworks.” [8]

Since both citizens and city management dealt well with the heavy stress caused by this drought, it can be used as an example for what to do in the case of future climate disasters. It also offers the warning that one challenge often leads to other potential challenges that must be taken seriously, like the fires and possible typhoid outbreaks. Oberlin demonstrated both prudence and flexibility in its response to the 1930 drought.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

“Condition of Crops Serious in Vicinity.” Oberlin News-Tribune, July 31, 1930.

“Drought and Heat Wave Hit Farms Throughout Middle West.” Oberlin News-Tribune, August 7, 1930.

Retrieved 5 August 2021

“Citizens Ordered to Reduce All Water Consumption to the Minimum Until Rain Comes.” Oberlin News-Tribune, August 21, 1930.

“Thirty Days Water Supply.” Oberlin News-Tribune, August 21, 1930.

“Danger From Typhoid Fever at This Time.” Oberlin News-Tribune, August 21, 1930.

“Must Conserve Water Supply.” Oberlin News-Tribune, September 11, 1930.

“Water Shows Increase in Conduit Line.” Oberlin News-Tribune, September 25, 1930.

“Water Situation Remains Serious.” Oberlin News-Tribune, November 6, 1930.

“New Supply of Water to Aid Village.” Oberlin News-Tribune, November 13, 1930.

“Has Kept Diary For Last Sixty Years.” Oberlin News-Tribune, January 1, 1931.

“Forty-Four Fires Caused $2,670 Damage.” Oberlin News-Tribune, January 8, 1931.

“Indefinite Supply of Water Now Assured.” Oberlin News-Tribune, March 5, 1931.

Aier. “Cost of Living Calculator: What Is Your Dollar Worth Today?” AIER. American Institute for Economic Research, June 15, 2021. https://www.aier.org/cost-of-living-calculator/

Straszheim, Robert E, and Falconor, J I. “The Drought in 1930.” Mimeograph Bulletin 37 [of the Department of Rural Economics at Ohio State University] (April 1931). Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/159598534.pdf

FOOTNOTES:

[1] “Indefinite Supply of Water Now Assured.” Oberlin News-Tribune, March 5, 1931.

[2] “Thirty Days Water Supply.” Oberlin News-Tribune, August 21, 1930.

[3] “New Supply of Water to Aid Village.” Oberlin News-Tribune, November 13, 1930.

[4] “Must Conserve Water Supply.” Oberlin News-Tribune, September 11, 1930.

[5] “Danger From Typhoid Fever at This Time.” Oberlin News-Tribune, August 21, 1930.

[6] “Danger From Typhoid Fever.” Oberlin News-Tribune.

[7] “Has Kept Diary For Last Sixty Years.” Oberlin News-Tribune, January 1, 1931.

[8] “Indefinite Supply Water Assured.” Oberlin News-Tribune.