“Unyielding dedication”: Stephen Johnson on Richard Lothrop’s Legacy

Friday, July 22nd, 2016by Hannah Cipinko, Oberlin Heritage Center Junior Intern

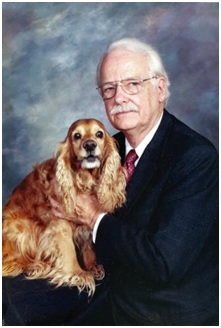

Richard Lothrop (1925-2015), pictured with his cocker spaniel Rusty. [1]

Oberlin is well known for its historic qualities, its strong sense of community, and high amount of community involvement. In this post we will explore the legacy of an extraordinary historian and community member, the late Richard Lothrop. His legacy lives on today through his impressively thorough collection of significant documents and newspapers from Oberlin’s history, which are now both preserved and available for research at the Oberlin Heritage Center.

Richard Lothrop was born in 1925 in Washington, D.C., and came to live in Oberlin at only three months old. He lived with his father, mother, and younger sister. His father was a professor of chemistry at Oberlin College. After graduating from Oberlin High School, Lothrop attended the College of Wooster and then worked in various college administration positions until taking a teaching job at Fairview High School. Richard went on to become “archivist emeritus” at Oberlin’s Christ Episcopal Church, and was named “Oberlinian of the Year” in 1996. This quote from his 2015 obituary in the Oberlin News-Tribune demonstrates the extent of his “unyielding dedication to his hometown”. . .

“Richard’s legacy included an almost obsessive trait to save newspaper clippings and document people, places, and events. He kept hundreds of files on subjects ranging from Oberlin events, Oberlin residents, and Oberlin College students, faculty, and staff to trains, planes, automobiles, and stamps!”[2]

I spoke with Oberlin Heritage Center Board of Trustees member Stephen Johnson, who is undertaking the immense project of sorting and preserving the files for posterity, to find out more about both Oberlin’s more recent history and Lothrop’s legacy of preservation.

Hannah Cipinko (HC): To start us off, how long have you been working with the Oberlin Heritage Center?

Steve Johnson (SJ): Well, I’ve been a trustee now for five years, and I’ve had an association with them for over twenty. We’ve been members for a long, long time. And my father was president for thirteen years of the predecessor of the Oberlin Heritage Center, O.H.I.O (Oberlin Historical and Improvement Organization) so that’s where I got my interest.

HC: Do you know how the Heritage Center in particular came to possess these documents instead of any other organization?

SJ: Our former executive director Pat Murphy was friends with Dick Lothrop and knew of his collection. Dick had assured OHC that upon his death we would receive all this material. When he went into a nursing home . . . we ended up with twelve boxes of this material, so now we’re in the process of going through it.

HC: What is that process like? Do you grab a file, or go alphabetically, and just dive in?

SJ: We’ve been working through it alphabetically. You open a file, and then . . . I sort the files into people, obituaries, and then miscellaneous, which is anything from churches, or town events, businesses in town, you know . . . anything that doesn’t qualify as people. . . We also sort out any documents from college publications because the college already has those in their archives, and there’s no need to duplicate that here . . . Once it’s sorted out, it has to be copied onto acid free paper and filed.

HC: What do you consider the most interesting story or item you have discovered so far?

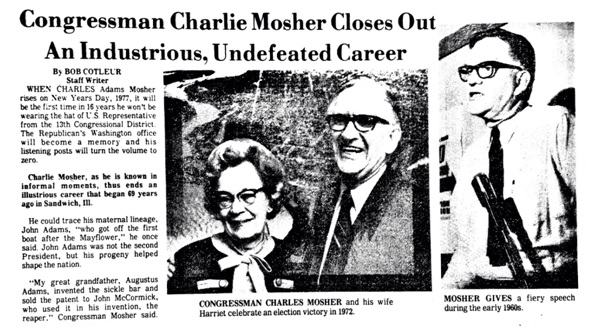

SJ: I recently ran into a big stack of articles on our former congressman from Oberlin, who had also been the editor of the Oberlin News-Tribune, Charles Mosher. That was really fascinating to go through, it turns out he was quite an eloquent speaker and writer. So that was fun [laughs].

An article about Charles Mosher found in Lothrop’s collection.

The Lorain Journal, December 12th 1975 [3]

SJ: There have been articles that have gone back to World War II, which is an interest of mine, and it’s interesting to see what the town was doing as far as scrap drives, and that kind of thing, as well as the boys and women who went off to war. Then, some of the articles are from an Oberlin Times newspaper from way back in the beginning of the century, and anything in there is interesting, just to see what life was like way back when.

The newspapers back [from] anytime before 1945 are very social. So you get little half column inch things about Mrs. Jones who threw a party and tea was served with these little crumb cakes. You know, these little snippets of life in Oberlin.

HC: Things you wouldn’t ordinarily think of as history.

SJ: Exactly. It shows, definitely, a way of life that has changed. It’s all interesting stuff; when you look at it, it’s like a time capsule that you open up and all of a sudden it’s 70 years ago, 80 years ago, 90 years ago.

It’s interesting to see because sometimes you get articles that are very factual, very illuminating of a person or a thing, and then you’ll have a one column inch thing that he saved of somebody who got a traffic citation. So it’s everything in between. I’ve see the heights of Oberlin history, and I’ve also sort of seen some of the depths of Oberlin history, but it’s all history. It’s something we will keep.

HC: What’s really fascinating about this is that it’s not only a snapshot of Oberlin’s history, but also of the perspective of Richard Lothrop as someone immersed in Oberlin’s modern culture and history. Do you think there is anything to be learned about his perspective from what he chose to keep in his files? Were there any items in particular you were surprised to see that Lothrop preserved?

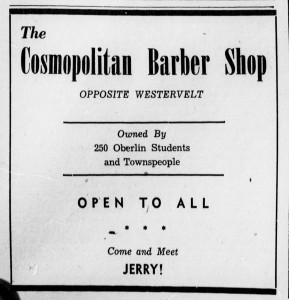

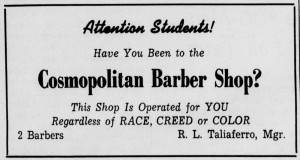

SJ: The thing that strikes me about this collection is just how all inclusive it is. It doesn’t seem like he left out much; if a new business opened in town and there was a newspaper article about it, he clipped it. If there was a newspaper article in the New York Times about somebody who did something fantastic, and he had an Oberlin connection, maybe graduated from Oberlin in 1935, he has that in there.

It’s an incredible collection, and I think the most amazing thing about it is how widespread it is. He didn’t focus in on just his friends or his acquaintances, he didn’t do just Oberlin government or Oberlin sports or anything else, it’s an all inclusive thing. And for him to sit there — I sometimes get a vision of him sitting alone in his house at night, going through all the newspapers, making these clippings, and filing them away. It must have taken an incredible amount of time.

HC: How long do you think it will take, in full, to sort through and organize these documents?

SJ: Right now, I’m at 13 months. I probably have close to at least 200 hours at this point, probably more than that. I can see another, two years to finish it up. It’s all got to be filed, Linda Gates here at OHC has been doing all of the filing, as I get things done she grabs them and files them. I think I’m on box four or five; I’m into the M’s right now [laughs]. I have six or seven boxes left to go. So that’s at least another year and a half. It will be three years by the time everything is done completely.

It is clear that Lothrop’s legacy is particularly present at the Oberlin Heritage Center, whose mission it is to preserve and share local history and stories such as his. Lothrop’s obituary says it best: “History was his passion. He loved to tell stories. He had stories to tell.”[2] The Oberlin Heritage Center will continue to share his stories alongside others with the addition of his files to our collections.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

“An Interview with Steve Johnson.” Interview by author. June 22, 2016.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Oberlin News-Tribune. “Richard Lothrop.” Oberlin News-Tribune, August 31, 2015. 2015. Accessed June 18, 2016. http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/theoberlinnewstribune/obituary.aspx?pid=175693314. Web.

[2] “Richard Lothrop Obituary.” Cowlingfuneralhomeoh.com. 2015. Accessed June 20, 2016. http://www.cowlingfuneralhomeoh.com/obits/obituary.php?id=657250. Web.

[3] Cutleur, Bob. “Congressman Charlie Mosher Closes Out An Industrious, Undefeated Career.” The Lorain Journal, 12 Dec. 1975: n. pag. Print.