“Odious business” in Oberlin: Northern States’ Rights, Part 3

Thursday, January 23rd, 2014by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent

“An act to prevent slaveholding and kidnapping in Ohio” – REPEALED!

“An act to prohibit the confinement of fugitives from slavery in the jails of Ohio” – REPEALED!

Monroe’s 1856 Habeas Corpus Act – REPEALED!

In early 1858 the newly elected Democratic Ohio General Assembly wasted no time attacking Ohio’s personal liberty laws, which had been passed by the prior Republican legislature to counteract the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. (See my Northern States’ Rights, Part 1 and Part 2 blog posts). Between February and April they repealed the three laws listed above. They also attempted to repeal a fourth law, “An act to prevent kidnapping”, but were unsuccessful at that, making it the only Ohio personal liberty law left standing. [1]

Although this might sound like a massive backlash on the part of the Ohio electorate, it might not have been quite as dramatic as it appears. Ohio had a long history of flip-flopping between anti-slavery and anti-black legislatures from one election to the next. Ohio historian William Cochran also attributed it to voter “apathy” in an off-year election, and to the Republicans “pat[ting] themselves on the back and go[ing] to sleep.” But it’s also clear that the Democrats made a campaign issue of Republican policies, including the personal liberty laws, and it’s reasonable to assume that at least some conservative Ohioans were energized to vote Democratic by their apprehensions over the “radical” anti-slavery policies of the Republican legislature. [2]

One thing was certain though, the repeal of the personal liberty laws by the Democratic legislature opened up Ohio as a potential hunting ground for slavecatchers. Oberlin, in particular, was vulnerable, both because it was widely known to be a haven for people seeking freedom from slavery, and also because one of Oberlin’s few pro-slavery residents, Anson P. Dayton, had just been appointed U.S. Deputy Marshal by the pro-slavery administration of President James Buchanan. [3]

The years prior to 1858 had been very quiet in northeast Ohio in terms of slavehunting activities. The Cleveland Leader noted that “during the whole of President Pierce’s and the half of Mr. Buchanan’s Administration no efforts were made in these parts, in a business so odious to the people.” But that would change now. According to John Mercer Langston, who was Town Clerk at the time, in the Spring of 1858 “alarm was created by the presence of negro-catchers from Kentucky and other neighboring Southern States, who were prowling in stealth and disguise about this holy place in search of their fleeing property.” In mid August, an attempt was made to capture the Wagoner family, and on August 20, Marshal Dayton and 3 cohorts attempted unsuccessfully to seize an African American woman and her children. The attempt was repeated three nights later. But Oberlin demonstrated that it could hold its own even without the support of state law, as all of these attempts were thwarted by a vigilant community. In one case, James Smith, on hearing that Marshal Dayton was conspiring with slaveholders in North Carolina to capture him, chased the Marshal into the Palmer House (at the site of the present day Oberlin Inn) and struck him with a cane. [4]

In September, another Oberlin resident noted that “it was also universal town talk that there were several Southerners at [Chauncey] Wack’s tavern, whose business it was supposed to be to seize and carry off some of the citizens of the place.” [5] And indeed one of those Southerners would conspire with a U.S. Marshal and two other men to abduct John Price, an alleged fugitive slave living in Oberlin. The abduction and rescue of Price is a much publicized event known as the “Oberlin-Wellington Rescue”, so I won’t go into details here, but I thought it might be interesting to examine how the Rescue related to Ohio’s personal liberty laws. (For details about the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, see The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue 1858)

As we shall see, Monroe’s Habeas Corpus Act might have been written for just such an event as the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, and it’s interesting to note that the Republican Governor and the Republican state supreme court proceeded as if that law had never been repealed! They defied the Buchanan Administration in Washington D.C. and the slaveholder dominated United States Supreme Court, and opened the door for a potential armed confrontation between the state and federal governments that could have dwarfed the “Battle of Lumbarton“, fought two years earlier.

After dozens of Oberlin and Wellington men were arrested by the federal government for rescuing John Price from his captors, the Ohio Supreme Court issued writs of habeas corpus to bring two of the rescuers before it to determine for itself whether the federal government had a right to imprison them. According to historian Thomas D. Morris in his acclaimed study of the personal liberty laws of the North, this was in direct defiance of the United States Supreme Court, which had just weeks earlier, in another Fugitive Slave Law case, ruled that a state court had no authority to interfere with, or even question, a detention once it learned that the prisoners were held under authority of the federal government (Abelman v. Booth). In addition, the writs weren’t directed to the federal law enforcement officers who had arrested the rescuers (and who likely would have ignored the writs); instead they were directed to the Cuyahoga County Sheriff, who had jurisdiction over the jail the rescuers were being held in. This is exactly what would have happened under the Monroe law. The Buchanan Administration angrily protested that “the State Court have no authority to meddle with this business.” But the Sheriff, who was sympathetic to the rescuers, voluntarily complied with the writs. (He would have been required to under the Monroe law.) This left the federal law enforcement agents with no choice but to accompany the Sheriff and their prisoners to the state court in Columbus. However, they were under strict orders from the Buchanan Administration that the rescuers “must under no circumstances be surrendered”, even if the Ohio Supreme Court ordered them released. [6]

While all this was going on, Ohio Governor Salmon Chase was publicly telling a large crowd in Cleveland that he would go along with whatever the Ohio Supreme Court decided, and that if they decided the rescuers should be set free, then “so long as Ohio was a Sovereign State, that process should be executed.” [7] Chase, of course, knew that the federal law enforcement officers would never free the rescuers voluntarily, and thus it would appear he was prepared to use force to free them, as would have been authorized by the terms of Monroe’s repealed law. As it turns out though it was all a moot point, since the Ohio Supreme Court decided by a 3 to 2 margin that the imprisonment of the rescuers was indeed authorized by the U.S. Constitution (in spite of the judges’ own personal feelings). Thus another armed confrontation between the federal government and the state of Ohio was avoided, but it was nonetheless a disheartening verdict for the rescuers and a sad day for Oberlin.

But all was not yet lost. There was still one arrow left in the quiver. Ohio still had one lonely personal liberty law left on the books, the 1857 “act to prevent kidnapping”. If you recall from Part 1 of this series, that law mandated a minimum sentence of three years hard labor in the state penitentiary for anyone who should “forcibly or fraudulently carry off or decoy out of this state any black or mulatto person… claimed as fugitives from service or labor, or shall attempt to [do so], without first taking such black or mulatto person or persons before the court, judge or commissioner of the proper circuit, district or county.” In February, 1859, a Lorain County Grand Jury issued an indictment under that law against the four men (including the U.S. Marshal) who had captured John Price. Since these men were frequently coming to northeast Ohio to testify against the rescuers at their trials, it set up an interesting cat-and-mouse game where Lorain County Sheriff Harmon Burr (an Oberlin College alumnus) tried to arrest the slavecatchers, while the federal government tried to protect the slavecatchers so they could testify against the rescuers. This led the anti-Oberlin Cleveland Plain Dealer to scoff, “Oberlin has now taken up and become the champion of the Southern doctrine of ‘State Rights’.” [8]

Lorain County Sheriff Harmon Burr

(from Lorain County Sheriff’s Office)

Ultimately Sheriff Burr did succeed in arresting the slavecatchers and in convincing them that an angry Lorain County jury would almost certainly convict them at their trial, which was scheduled to begin in July. The slavecatchers wanted no part of a three to eight year sentence of hard labor in the notorious Ohio State Penitentiary, so they accepted a deal where the county would drop the charges against them if they persuaded the federal government to drop the charges against the rescuers. Since the testimony of the slavecatchers was essential to the case against the rescuers, the federal government had no choice but to comply with their request. And so it was that the most conservative of Ohio’s personal liberty laws ultimately led to the liberty of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescuers. News of Oberlin’s triumph spread nationwide and even overseas, with the Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican exulting, “So ends the famous rescue cases and it may be safely set down as a fixed fact that they are the last of the sort in Ohio. The persecution of Christian men for showing kindness to runaway negroes is a losing operation socially and politically.” [9]

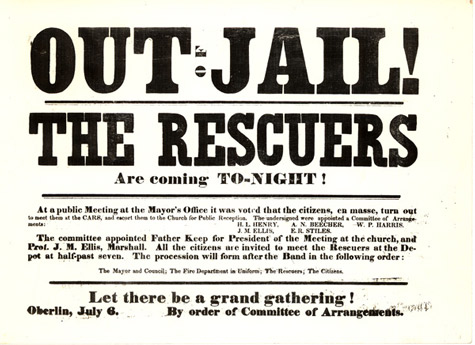

Poster announcing celebration for Rescuers

(courtesy Oberlin College Archives)

And it was indeed a “losing operation” for the Democrats, as the Republicans regained control of the Ohio General Assembly in the elections of 1859. Voter disgust at the Fugitive Slave Law and the treatment of the rescuers by the federal government was a contributing factor to yet another electoral flip-flop. Beginning their new term in early 1860, James Monroe and other “radical” Republicans now looked to try and reinstate the repealed personal liberty laws. But the situation was different than it had been the last time the Republicans were in control. Now the Republicans were looking towards the Presidential election of 1860 and the very real possibility of a first-time ever Republican victory placing an anti-slavery President in the White House – IF they played their cards right. And that meant playing no cards that would lead the public to perceive them as being too radical. This was especially true after John Brown’s raid of the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October, 1859. Republicans wanted to distance themselves from radical and violent abolitionism as much as possible. As a result, the Republican Ohio General Assembly passed no personal liberty laws*, and other northern states refrained from radical legislation as well. [10]

The strategy paid off, and Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected to the Presidency in November. But almost immediately after his election, slaveholding states started seceding from the Union. Despite the fact that Republicans had shown restraint in passing new personal liberty laws, the seceding states included the personal liberty laws in a list of grievances justifying their secession. Texas, in its “Declaration of the Causes” of secession, claimed the following:

“[Texas] was received [into the federal Union] as a commonwealth holding, maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery– the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits– a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time… But what has been the course of the government of the United States, and of the people and authorities of the non-slave-holding States, since our connection with them? …

The States of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, Michigan and Iowa, by solemn legislative enactments, have deliberately, directly or indirectly violated the [fugitive slave clause] of the federal constitution, and laws passed in pursuance thereof; thereby annulling a material provision of the compact, designed by its framers to perpetuate the amity between the members of the confederacy and to secure the rights of the slave-holding States in their domestic institutions– a provision founded in justice and wisdom, and without the enforcement of which the compact fails to accomplish the object of its creation. Some of those States have imposed high fines and degrading penalties upon any of their citizens or officers who may carry out in good faith that provision of the compact, or the federal laws enacted in accordance therewith.

In all the non-slave-holding States, in violation of that good faith and comity which should exist between entirely distinct nations, the people have formed themselves into a great sectional party, now strong enough in numbers to control the affairs of each of those States, based upon an unnatural feeling of hostility to these Southern States and their beneficent and patriarchal system of African slavery…” [11]

The secession of the slaveholding states ultimately led to civil war, and civil war moved the Fugitive Slave Law controversy to a new forum and its combatants to new battlefields. But finally, in 1864, the United States Congress repealed the notorious Fugitive Slave Law. The next year the 13th amendment of the United States Constitution was ratified, abolishing slavery nationwide. And two months after that, the Ohio General Assembly finally retired its lone surviving personal liberty law, “An Act to prevent kidnapping” – the law that had brought to Oberlin one of the greatest triumphs and most joyous celebrations of its rich and colorful history.

* Historians have traditionally taken the stance that this General Assembly passed no new personal liberty laws. Since I wrote this, however, I’ve discovered that the Republicans discreetly passed what amounted to a low-key personal liberty law in 1860. This law would have an impact on the infamous Lucy Bagby case of 1861, and will be discussed in detail in a future blog. – Ron Gorman, Nov. 19, 2016

SOURCES CONSULTED:

William Cox Cochran, The Western Reserve and the Fugitive Slave Law

Nat Brandt, The Town that Started the Civil War

Thomas D. Morris, Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North 1780-1861

“A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union”, Declaration of Causes of Seceding States, University of Tennessee

John Mercer Langston, From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol

William Cheek, John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1829-65

Jacob Rudd Shipherd, History of the Oberlin Wellington Rescue

James Monroe, Speech of Mr. Monroe of Lorain, upon the Bill to Repeal the Habeas Corpus Act of 1856

James Monroe, Oberlin Thursday Lectures, Addresses, and Essays

Paul Finkelman, An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity

Acts of the State of Ohio, Volume 63

The public statutes at large, of the state of Ohio [1833-1861], Volume 4

“Harmon E. Burr”, Whiteside County Biographies

General catalogue of Oberlin college, 1833 [-] 1908, Oberlin College Archives

Robert Samuel Fletcher, A history of Oberlin College: from its foundation through the Civil War, Volume 1

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Public, Vol 4, pp. 3028, 3036; Cochran, p. 118

[2] Cochran, p. 118; Monroe, Speech, pp. 3, 4, 13

[3] Cheek, p. 316

[4] Cochran, pp. 119, 121; Fletcher, Chapter XXVI; Langston, p. 183

[5] Shipherd, p. 32

[6] Morris, p. 187; Finkelman, p. 178; Brandt, p. 202

[7] Cochran, p. 186

[8] Cochran, pp. 197-198; Brandt, pp. 172-173; General Catalogue, p. 336; “Harmon”

[9] Cochran, p. 201

[10] Cochran, pp. 209-210; Monroe, Thursday, p. 121; Morris, pp. 188-190, 219-222

[11] “A Declaration”