William Howard Day & Lucie Stanton

Wednesday, April 2nd, 2014by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent

In 1850, a young African American couple from Oberlin, acclaimed as up-and-coming spokespersons against slavery and racial injustice, gazed with optimism towards a future of bright hope for themselves, their race, and their country. But as they took their leave of Oberlin to spread that hope through Ohio and the nation, they could little imagine the disappointment and disillusion they would suffer over the next several years. In the long run they would see their efforts rewarded, but only after a temporary separation from their country and a permanent separation from each other. Their names were William Howard Day and Lucie Stanton.

William Howard Day

(courtesy University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

William Howard Day came to Oberlin in 1843 at the age of 17, where he enrolled in the collegiate program at Oberlin College. He brought with him a strong disdain for slavery and racial injustice, learned from his mother, who had escaped from slavery in upstate New York and settled in Manhattan. It was there, as a nine year old boy, that William witnessed the terrible race riots that wreaked havoc on Reverend Charles G. Finney’s chapel and the home of abolitionist Lewis Tappan. But now, attending the college that Finney and Tappan had done so much to turn into an abolitionist stronghold, William wasted no time in making his mark. [1]

He became close friends with George Vashon, who in 1844 would become the first black student to receive a Bachelor’s Degree from Oberlin College, and Sabram Cox, another African American who was one of Oberlin’s most important Underground Railroad operatives. Working closely with Vashon and Cox, William became a leading orator and organizer of the Oberlin black community. On August 1, 1844, as Oberlin’s black citizens celebrated their third annual observance of the anniversary of British emancipation in the West Indies, William stood before the crowd to “commemorate the emancipation of eight hundred thousand of our fellow men from the galling yoke of slavery” and urged his “‘Colored friends [to] struggle on – struggle on! Be not despondent, we shall at last conquer.” The audience listened to William’s speech with such “great interest” that they requested it be reprinted in the Oberlin Evangelist. [2]

During the long winter recesses between semesters, William would travel to Canada and teach in the many black settlements founded there by refugees from American slavery. He also found employment in Oberlin during the school months as a typesetter for the Oberlin Evangelist. And as new students enrolled in Oberlin College, he developed new friendships. Among these were Charles and John Mercer Langston, and Lawrence W. Minor, all of whom would become important contributors to Oberlin’s black community. Another new friendship was with Lucie Stanton. [3]

Lucie (often spelled Lucy) came to Oberlin in 1846, William’s senior year. She had been raised in Cleveland in a home that was a station on the Underground Railroad. In Cleveland she attended public school with white children, but eventually she was forced, “heart-broken”, to leave because of her race. It was against state law at that time for black children to attend public school, so her stepfather, a wealthy African American barber, started his own private school in Cleveland, which Lucie attended. Thus Lucie, like William, came to Oberlin highly conscious of American racism and slavery. She and William naturally gravitated towards each other and began a courtship that would last several years. [4]

William graduated in 1847, becoming the third black student to earn a Bachelor’s Degree from Oberlin College. He was chosen to give a commencement address, which he entitled “The Millenium of Liberty” and was reprinted in the Oberlin Evangelist. [5] William remained in Oberlin after graduating, continuing to work for the Evangelist, and helping to organize Oberlin’s “vigilance committee”- black residents that would protect the community against “men-thieves”. In 1848, William, together with Sabram Cox, Lawrence Minor, John Watson, and Harlow H. Pease (the white nephew of Oberlin’s first resident, Peter Pindar Pease) called together a “Meeting of Colored Citizens” of Lorain County, where they passed eleven resolutions, including: [6]

1. Resolved, That we the colored citizens of Lorain county hereby declare, that whereas the Constitution of our common country gives us citizenship, we hereby, each to each, pledge ourselves to support the other in claiming our rights under the United States Constitution, and in having the laws oppressing us tested…

4. Resolved, That we still adhere to the doctrine of urging the slave to leave immediately with his hoe on his shoulder, for a land of liberty…

5. Resolved, That we urge all colored persons and their friends, to keep a sharp look-out for men-thieves and their abettors, and to warn them that no person claimed as a slave shall be taken from our midst without trouble… [7]

William was making a name for himself as a superb organizer and orator, and he would be a driving force in local, state and national black civil rights/anti-slavery conventions for the next decade. In January, 1849, at the “State Convention of the Colored Citizens of Ohio” in Columbus, William delivered a speech in the Hall of Representatives of the Ohio General Assembly, becoming the first black person to address a session of that body. It was an important milestone for Ohioans and for 23-year-old William, as he urged the Assembly to repeal Ohio’s notoriously discriminatory “Black Laws”:

We believe … that every human being has rights in common, and that the meanest of those rights is legitimately beyond the reach of legislation, and higher than the claims of political expediency…

We ask for equal privileges, not because we would consider it a condescension on your part to grant them – but because we are MEN, and therefore entitled to all the privileges of other men in the same circumstances…

We ask for school privileges in common with others, for we pay school taxes in the same proportion.

We ask permission to send our deaf and dumb, our lunatic, blind, and poor to the asylums prepared for each.

We ask for the repeal of the odious enactments, requiring us to declare ourselves “paupers, vagabonds, or fugitives from justice,” before we can “lawfully” remain in the State.

We ask that colored men be not obliged to brand themselves liars, in every case of testimony in “courts of justice” where a white person is a party…

We ask that we may be one people, bound together by one common tie, and sheltered by the same impartial law…

Let us … inform our opposers that we are coming – coming for our rights – coming through the Constitution of our common country – coming through the law – and relying upon God and the justice of our cause, pledge ourselves never to cease our resistance to tyranny, whether it be in the iron manacles of the slave, or in the unjust written manacles for the free. [8]

Ohio’s Black Laws had been in effect since the early days of statehood and had survived multiple attempts at repeal. But William’s timing was perfect in 1849. It so happened that the General Assembly was deadlocked between representatives of the Democratic and Whig parties, with a handful of abolitionist members of the new anti-slavery Free Soil Party holding the balance of power – and willing and able to wield that power effectively. And so, less than a month after William’s passionate appeal, the General Assembly voted by an overwhelming majority to repeal most of the Black Laws, and to permit public schooling of black children (albeit racially segregated, for the most part). It was a significant step forward for Ohio, and a major victory for William. [9]

But William wasn’t the only one achieving major breakthroughs during this period of time. Back at Oberlin College, Lucie was elected the first black President of the Ladies’ Literary Society in 1850, and then became the first African American woman in the country to earn a college degree. Lucie also was chosen to deliver a commencement address, which was also reprinted in the Oberlin Evangelist. With a “charming voice, modest demeanor, appropriate pronunciation and graceful cadences”, she delivered “A Plea for the Oppressed”: [10]

Dark hover the clouds. The Anti-Slavery pulse beats faintly. The right of suffrage is denied. The colored man is still crushed by the weight of oppression. He may possess talents of the highest order, yet for him is no path of fame or distinction opened. He can never hope to attain those privileges while his brethren remain enslaved. Since, therefore, the freedom of the slave and the gaining of our rights, social and political, are inseparably connected, let all the friends of humanity plead for those who may not plead their own cause…

Truth and right must prevail. The bondsman shall go free. Look to the future! Hark! the shout of joy gushes from the heart of earth’s freed millions! It rushes upward. The angels on heaven’s outward battlements catch the sound on their golden lyres, and send it thrilling through the echoing arches of the upper world. How sweet, how majestic, from those starry isles float those deep inspiring sounds over the ocean of space! Softened and mellowed they reach earth, filling the soul with harmony, and breathing of God–of love–and of universal freedom. [11]

And so with boundless optimism, Lucie left Oberlin and found employment in Columbus, teaching in the newly established public schools for black children, while William moved to Cleveland, where he became a correspondent for an anti-slavery newspaper called the Daily True Democrat and was active in the Cleveland vigilance committee, assisting refugees from slavery. He also remained active in conventions, and in 1851 he took aim at the Ohio Constitution and its restriction of voting rights to “white male inhabitants” only. [12]

The discriminatory word “white” in the Ohio Constitution had been a target of progressives for decades, even though the Ohio courts had since diluted it to the point that light-skinned black men like William could now vote in some localities. Even so, William set his sights at eliminating the word completely, and a state Constitutional Convention held in 1850-1851 gave him just that opportunity. A “State Convention of Colored Men” was held concurrently in Columbus, and William was given the chance to address both conventions simultaneously in January, 1851. Using statistics compiled by John Mercer Langston, William told the conventions: [13]

We respectfully represent to you, that the continuance of the word “white” in the Ohio State Constitution, by which we are deprived of the privilege of voting for men to make laws by which we are to be governed, is a violation of every principle [of our fathers of the revolution]…

Again, colored men are helping, through their taxes, to bear the burdens of the State, and we ask, shall they not be permitted to be represented?… In returns from nineteen counties represented, we find the value of real estate and personal property belonging to colored persons in those counties, amounting to more than three millions of dollars… [We] think the amount above specified, certainly demands at your hands some attention, so that while colored men bear cheerfully their part of the burdens of the State, they may have their part of the blessings…

We ask, Gentleman, in conclusion, that you will place yourselves in our stead,- that you will candidly consider our claim, and as justice shall direct you, so to decide. In your hands, our destiny is placed. To you, therefore, we appeal. We look to you “To give us our rights – for we ask for nothing more.” [14]

But this time William’s timing wasn’t so good. In fact, it was off by decades. The delegates of the Constitutional convention voted overwhelmingly to retain the word “white” in the new Constitution.

It was the first of a long string of disappointments, but still William and Lucie battled on. In 1852 they joined in matrimony and Lucie returned to Cleveland. In 1853, William started his own newspaper, The Aliened American, the first African American newspaper in Ohio. The paper employed a highly impressive and “intelligent corps of male and female correspondents”, which included Lucie, who wrote a fictional story for the first issue about an enslaved brother and sister. The story, entitled “Charles and Clara Hayes”, has been recognized as “the first instance of published fiction by a black woman”. The Aliened American dealt with local and state racial issues, but William also tackled national issues, including in his first issue an editorial rebuttal of President Franklin Pierce’s recent inaugural address: “The President forgot, or if he did not forget, cared not to remember, that the South, for whom he was pleading, tramples every day upon the Constitutional rights of free citizens.” [15]

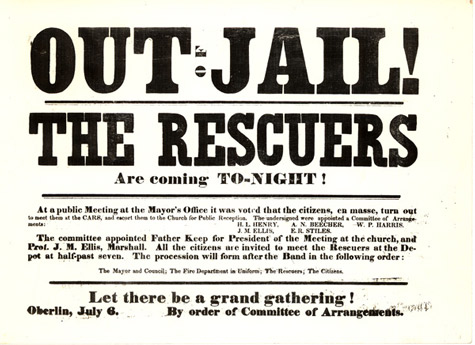

But the trampling of Constitutional rights, by the North as well as the South, was taking its toll. In 1854, the Ohio General Assembly expelled William from the Senate press gallery largely because of his race. (See my Oberlin Commenst this War! blog) In 1850 the U.S. Congress passed the notorious Fugitive Slave Law, and the Pierce Administration now demonstrated the lengths the government would go to in order to enforce it when they sent “several companies of marines, cavalry and artillery” to Boston to rendition a single fugitive, Anthony Burns. And the United States Congress overturned the long-respected Missouri Compromise by allowing slavery into U.S. territories that had been guaranteed free. William, who had been criticized by some of the more militant black leaders for “wrap[ping] the stars and stripes of his country around him”, began to take a more militant stance himself. The crowning blow came in 1856, when William and Lucie were returning from a trip to the black settlements in Canada and ended up making the long journey by train and wagon because they were denied a berth on a Michigan passenger boat due to the color of their skin. The incident, and the ensuing unsuccessful lawsuit against the boat operator, devastated William emotionally and financially, and crushed his remaining faith in American justice. [16]

And so it was, in 1856, that William and Lucie joined thousands of other refugees from American racial oppression and relocated to Canada. There they had a child and took an active role in helping the Canadian vigilance committees protect even Canadian blacks from being kidnapped into American slavery. In 1858, when the radical white Ohio abolitionist, John Brown, visited Canada to recruit support for a planned slave insurgency in the heart of the American south, William agreed to print his “Provisional Constitution” for him, but refused to participate any further. [17] (An original Day print of this document recently fetched $22,800 at auction.)

In 1859 William sailed to Britain to solicit financial support “to establish a Press … for the special benefit of the Fugitive Slaves and coloured population” of Canada. He was still there when the American Civil War broke out in 1861, and so he also urged the British people to reject the Confederacy and support the Union. But he also solicited funds for a new colonization effort in Africa led by his militant friend, Martin Delany. [18]

The long separation from his wife, however – leaving her to raise their child alone – irreparably damaged their marriage. When President Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the Days found faith enough in the United States to return and dedicate themselves to the advancement of the freedmen, but they would go in separate directions. William became a superintendent of schools for the Freedmen’s Bureau and ultimately President of the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania school board. Lucie had to overcome the Victorian-era stigma of being a single mother (you can read about her trials and tribulations here), but she eventually fulfilled a long-term ambition “to go South to teach”, teaching black children in Georgia and Mississippi. After finalization of the divorce, she remarried, and under the name of Lucie Stanton Sessions was an active officer of the Women’s Relief Corps and a local temperance society. [19]

Lucie Stanton Sessions in her later years

Although the boundless, youthful optimism of their Oberlin days may have been tempered, both Lucie and William continued to “struggle on” and dedicated their lives to the cause of “universal freedom.”

Sources consulted:

Todd Mealy, Aliened American: A Biography of William Howard Day: 1825 to 1865, Volume 1

Stephen Middleton, The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio

Frank Uriah Quillin, The Color Line in Ohio: A History of Race Prejudice in a Typical Northern State

Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection; State Convention of the Colored Citizens of Ohio, “Minutes and Address of the State Convention of the Colored Citizens of Ohio, Convened at Columbus, January 10th, 11th, 12th, & 13th, 1849”

State Convention of Colored Men, “Address to the Constitutional convention of Ohio / from the State convention of colored men, held in the city of Columbus, Jan. 15th, 16th, 17th, and 18th, 1851”

Ellen NicKenzie Lawson with Marlene D. Merrill, The Three Sarahs: Documents of Antebellum Black College Women

“Meeting of Colored Citizens”, The Liberator, March 2, 1849, Vol XIX, No. 9, Page 1

The Oberlin Evangelist (see footnotes for specific issues)

C. Peter Ripley, et al, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume IV, The United States, 1847-1858

C. Peter Ripley, et al, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume II, Canada, 1830-1865

William Cheek, John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1829-65

William M. Mitchell, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom

Victor Ullman, Look to the North Star; a life of William King

“Ohio Constitution of 1803 (Transcript)”, Ohio History Central

James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom

Oberlin Heritage Center; Harlow Pease, “Harlow Pease (1828-1910)”

General catalogue of Oberlin college, 1833 [-] 1908, Oberlin College Archives

“Catalogue and Record of Colored Students,” 1835-62, RG 5/4/3 – Minority Student Records, Oberlin College Archives

Robert Samuel Fletcher, A history of Oberlin College: from its foundation through the Civil War, Volume 1

Footnotes:

[1] Mealy, pp. 47-50

[2] Mealy, pp. 120-121; Oberlin Evangelist, Nov 6, 1844

[3] Mealy, pp. 121-126

[4] Lawson, pp. 190-191

[5] “Catalogue and Record”; Oberlin Evangelist, Oct. 13, 1847

[6] Mealy, pp. 134, 146; Oberlin Heritage Center

[7] “Meeting of Colored Citizens”

[8] Samuel J. May Anti-slavery collection

[9] Quillin, pp. 39-40

[10] Lawson, pp. 192-193; Oberlin Evangelist, Nov 6, 1850

[11] Oberlin Evangelist, Dec 17, 1850

[12] Mealy, pp. 169-172; “Ohio Constitution”

[13] Ripley, Vol. IV, p. 225; Cheek, p. 153

[14] “Address to the Constitutional convention”

[15] Ripley, Vol. IV, pp. 215, 150; Lawson, pp. 196-197

[16] McPherson, p. 119; Ripley, Vol. IV, p. 75; Mealy, pp. 238-243

[17] Mealy, pp. 268, 277

[18] Mitchell, pp. 171-172; Mealy, p. 316

[19] Lawson, pp. 198-201