The weary feet and willing shoulders of Almira Porter Barnes

Tuesday, March 22nd, 2016by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent, researcher, and trustee

Oberlin’s history is chock-full of people who have gained national and international recognition for their achievements, like Antoinette Brown (Blackwell) – the first female ordained minister in the United States. But none of these people, no matter how deserved their recognition has been, could have reached their lofty heights without standing on the shoulders of people who came before them. And Oberlin’s history is also chock-full of the unsung heroes and heroines who willingly offered those shoulders. Few of those unsung heroines are as fascinating to me as an obscure grandmother from upstate New York named Almira Porter Barnes. In an age when the conventional wisdom had it that a grandmother’s place was knitting by the fireside, this remarkable lady was traveling the northern United States and Canada, investigating and influencing, financing and philanthropizing, encouraging and endorsing the great reform movements of her day: abolitionism, universal education, temperance, and general moral reform. (And she did her share of knitting too, by the way, but not always by the fireside.) She left an indelible mark not only on Antoinette Brown, but on Oberlin as well.

Antoinette Brown

Almira Porter, of whom we unfortunately have no photographs, was born in Connecticut in 1786. In 1807 she married a tinsmith named Blakeslee Barnes. They moved to Troy, New York and had 6 children before Blakeslee died in 1823. She never remarried. It’s not clear how much of Almira’s considerable wealth came from her husband’s tinsmith business or from other sources, but she clearly weathered the economic depression of 1837 with plenty of wealth intact to donate and loan to worthy causes. She donated hundreds of dollars (at least) to Oberlin College, the Oberlin Board of Education and the Ladies’ Education Society of Oberlin (likely in the tens of thousands of dollars in today’s currency). [1]

Her interest in Oberlin likely began through friendship with the Shipherd family in Troy, whose scion, John Jay Shipherd, was the co-founder of Oberlin colony and college. After that she helped fund the Oberlin College education of her grandson, Francis Fletcher in the 1840s. She also took an active interest in the Oberlin College education of her nephew, future Oberlin College Professor Henry E. Peck. [2]

Henry Peck

(courtesy Oberlin College Archives)

Although Barnes never officially resided in Oberlin or enrolled in Oberlin College, she spent summers in Oberlin during the 1840s attending, for her own personal edification, the theology classes of Oberlin College Professor Charles G. Finney. Most of what we know about Barnes comes from three letters that she wrote from Oberlin to her daughter, Mrs. Laura Willard in Troy, during the summer of 1844. These letters shine an interesting light on early Oberlin and antebellum America. [3]

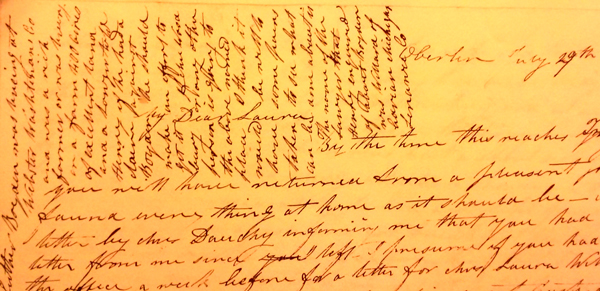

Sample from an Almira Porter Barnes letter. Not a millimeter of paper was wasted!

(courtesy Oberlin College Archives)

Barnes arrived in Oberlin in June that year, having started her journey with a boat ride from Troy to Buffalo via the Erie Canal. Along the way she arrived in Rochester just in time for a three day anti-slavery convention. Barnes considered skipping the convention, but her friends “urged me to stay and thought I should loose [sic] my standing in the Liberty Party if I did not.”

The Liberty Party was the first national abolitionist party, and it’s interesting that in this era of rough-and-tumble, male-only politics, Mrs. Barnes had any standing in a national political party to lose. Although abolitionists tended to be more progressive in the realm of women’s rights than American society in general, the political wing of the abolitionists was generally considered to be the least progressive of this group. But “the temptation of course was very great,” and Mrs. Barnes “concluded to remain through the week,” which she spent “very pleasantly.”

After the convention, she crossed Lake Erie to Cleveland, where she ran into Professor Calvin Stowe of Cincinnati’s Lane Seminary and William Beecher, the husband and brother, respectively, of Harriet Beecher Stowe, who eight years later would publish the epic anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Together the three of them took a carriage to “of course… the Temperance House.”

On the stagecoach to Oberlin the next morning, Barnes chanced to meet her college instructor, Professor Finney, who was also the renowned revivalist pastor of Oberlin’s one and only church, and several other Oberlinites, including her nephew, Henry Peck, and her grandson. The group had been attending a religious convention in Cleveland. But they returned early, “the convention having passed a vote that they would not let the Oberlin people say any thing, the object of the meeting was to promote pure and undefiled religion.” Ha! It wasn’t just abolitionism that made early Oberlin unpopular with its neighbors, but its unorthodox church and its unconventional pastor as well.

Reverend Charles G. Finney

(courtesy Oberlin College Archives)

Finally arriving in Oberlin, Barnes settled in for a long stay in the home of Oberlin College President Asa Mahan and his wife, Mary. Shortly afterwards word came from John Jay Shipherd “at Michigan” that he and his family were “all well and very happy and prospects flattering” – news which Barnes asked her daughter to relay to the Shipherd family in Troy. Shipherd had left Oberlin early that year for Olivet, Michigan to start a similar college and colony there. Despite the good tidings, he would be dead within three months.

Barnes continued to gently push the envelope of gender roles in Oberlin, as she sat in on Professor Finney’s classes in the male dominated Seminary. [4] But she was only in Oberlin for a month before she was already off on her next adventure. She had an opportunity to visit Canada and the Mahans encouraged her to go, insisting that “it would be a great satisfaction and encouragement to Mr. and Mrs. Rice to receive a visit” from her. The Rices were missionaries in the fugitive slave colony in Malden, Upper Canada (present day Windsor, Ontario). And so Barnes boarded a boat in Cleveland and crossed Lake Erie to Canada. Here she had an opportunity to visit the colonists who had escaped from American slavery. She wrote about this experience in her characteristically breathless style (which I’ve separated into paragraphs for ease of readability):

“Saturday morning we went out to call on the coulored [sic] people and spent most of the day, and I am sure I never spent a day so pleasantly in making calls as I did that day. All that we called upon had made their escape from Slavery and it was exceedingly interesting to have them tell how they managed to escape and what hardships and fatigue they endured in getting away and their suffering for fear they should be taken and carried back and especially their trial on account of leaving behind them their friends[;] prehaps [sic] a Husband had left a wife and children[,] or a wife her husband[,] or children had left parents that they should never see again[,] and they manifested as much feeling about it as any other people would.

The most that I talked with were those had learnt that they were to be soald [sic] from their familys [sic] and separated probably for ever[;] some had managed to get their families with them and some had escaped alone at the risk of their lives. They all seemed to feel as if they should have no mercy shown them if they should be overtaken. I asked one of them what he would have done if he had been pursued[;] he said before he would have been taken he would have killed his pursuers as quick as he would have killed a black snake, but he seemed to have a kind heart and said he should be very glad to see his Master their [sic], and would do him a favor as quick as he would anyone… But they all say if emancipation was to take place we would not be here long. The most of them have a little place and manage to get along some how.” [5]

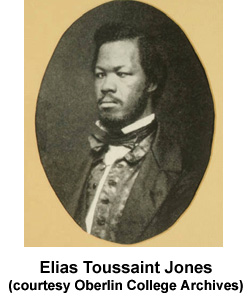

Barnes’ excursion to Canada was a short one, however. By August she was back in Oberlin, “regularly” attending Finney’s theology lectures “at nine o’clock and another at eleven”. “My time is almost constantly occupied in some thing that is or might be both interesting and improving,” she explained. One such activity was Oberlin’s third annual commemoration of British emancipation in the West Indies – where she was “invited to the first table” reserved for “professors families and distinguished strangers”. (See my “August First” blog for her description of this.) Of Oberlin Barnes said, “no one can realise [sic] the difference in which such things are regarded here from what they are in other places, who has not been here, not only in regard to the treatment of coulored people but almost every thing else.” [6]

With the end of the school year in August, Barnes returned home to New York, where she undoubtedly heard the startling news of the passing of John Jay Shipherd in September 1844. Shipherd’s death presented the Oberlin Collegiate Institute with a potential dilemma since they were occupying land that belonged to his estate. Concerned that the Shipherd family might choose to sell the land if they didn’t return to Oberlin, the college wondered where they might get the funds to buy it from them if necessary. With funds hard to come by, an agent for the college suggested that President Mahan “call upon Mrs. Barnes on his way to New York” and request a loan. He also noted that “Mrs. Barnes wishes [to buy or lease] a lot in Oberlin”, but only “if it was located right” – near President Mahan’s home or the chapel on Professor Street. (Since the Shipherds did move back to Oberlin, and there’s no record that Mrs. Barnes did, it appears that neither of these transactions took place.) [7]

The following year Henry Peck graduated from the Oberlin College seminary, but his aunt continued to attend Finney’s classes. In 1847, at the age of 61, she was joined in the classes by 22 year old Antoinette Brown, who had graduated from the Oberlin College Ladies’ Literary course. Brown would speak highly of “My friend Mrs. Barnes… who used to bring her knitting to our Oberlin class exercises.” (Wow – knitting during Finney’s classes. I doubt there were many people who could get away with that!) But Brown planned on taking the classes a step further than Barnes was. For Brown, the classes were more than just about personal edification. She wanted to preach, even though no woman had ever been ordained a minister and the college had made it clear that they weren’t about to graduate the first. Brown would not be deterred, however, and in 1850 she completed the program as a “resident graduate”, without being ordained or awarded a degree. [8]

Brown was now in a dilemma, however. She had completed her studies, but her life’s calling was unavailable to her because of gender discrimination. But the ubiquitous Mrs. Barnes saw a way to assist her young friend through her own New York City missionary work. “She now made this proposition to me,” Brown wrote, “if I would go to work in charities and in the slums, speaking as I could find opportunity in public and private, she would guarantee me a very fair salary and would find me a boarding-place with Zeruiah Porter Weed of the Class of 1838 Oberlin Literary.” Brown gratefully accepted the offer. [9]

On her way to New York City, Brown stopped at an abolitionist convention in Oswego, where she hoped to deliver an address of her own. But here too she encountered gender discrimination. Although many of the conventioneers were likely the same people who gave Mrs. Barnes “standing” in the political anti-slavery movement, they still weren’t prepared to allow a woman to speak in public. [10]

Disappointed, Brown made another stop, at the National Woman’s Rights Convention in Massachusetts. Here at last she was allowed to speak, impressing the audience with a lecture on one of her pet topics – that the Bible didn’t forbid women to speak in public. But when she finally arrived in New York City, she learned that most of the ladies in Barnes’ Guardian Society didn’t share that viewpoint. “The Guardian Society Ladies are of course not in perfect sympathy with my views,” Brown wrote, “& would not endorse the idea of my preaching on Sundays which was the plan we had formed.” Since Brown was dead set on preaching (with or without ordination), the women finally concluded mutually that it would be best to terminate “our contemplated enterprise.” Brown explained: [11]

“Mrs. Barns [sic] herself will still labor as a Missionary when she is able. She is a noble woman, has really liberal views & would gladly sustain me in the contemplated labors notwithstanding any prejudice on account of my womananity. So would Mrs. Weed. I admire many traits in her character very much. Neither of them would have fettered me in the least, yet they do not fully feel prepared to adopt all my views, & since there must be some prejudice against me I felt oppressed with the idea of compelling them to bear the credit of views which were not wholy [sic] their own though they had no hesitation about it. The society ladies are kind courteous & pleasant, but they cannot with their views encourage my preaching. So taking all things together we all thought it best to relinquish the enterprize [sic]… I can think of no person in the whole world that I would sooner have for my employer than Mrs. Barns, I love her very much; but I feel relieved that our engagement is broken.” [12]

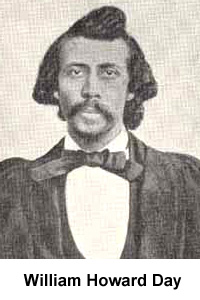

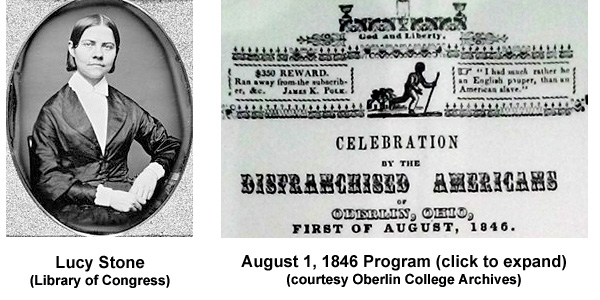

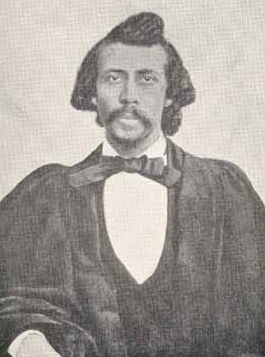

Eventually it would all work out for Brown, of course, as she was ordained in 1853, preached in several churches, married Samuel Blackwell, and became a successful speaker and writer on behalf of abolitionism, racial equality, women’s rights, and temperance. She also worked with her friend and fellow Oberlin College alumna, Lucy Stone, and others to found the American Woman Suffrage Association, which advocated women’s rights, but without sacrificing the principles of racial equality like other women’s organizations were then doing.

Almira Porter Barnes would only witness the early years of her young friend’s success, however, having passed away in 1858. The American Female Guardian Society would remember her as one of “three specially influential Vice Presidents” (Mary Mahan being another), whose “weary feet have safely reached that peaceful shore.” [13]

After all that traveling over all those years, the feet may indeed have been weary, but the shoulders were always willing.

To hear more about Almira Porter Barnes and other Oberlin abolitionists, please join us on Saturday, April 2, 2016 at 11:00 A.M. at the Oberlin Public Library for a presentation of “Old Secrets, New Stories of Oberlin’s Underground Railroad”

SOURCES CONSULTED:

Almira Porter Barnes to Mrs. Laura Willard, June 28, 1844, Oberlin College Archives (OCA), Robert S. Fletcher collection, RG 30/24, Box 3, Folder: “Correspondence – Misc pre-1865”

Almira Porter Barnes to Mrs. Laura Willard, July 29, 1844, OCA, Robert S. Fletcher collection, op. cit.

Almira Porter Barnes to Mrs. Laura Willard, August 12, 1844, OCA, Robert S. Fletcher collection, op. cit.

Carol Lasser and Marlene Deahl Merrill, ed., Friends and Sisters: Letters between Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell, 1846-93

Elizabeth Cazden, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, a Biography

Sherlock Bristol to Hamilton Hill, Oct 21, 1844, OCA, Robert S. Fletcher collection, RG 30/24, Box 14, Folder 9 (“Treasurer’s Office, File K”).

Sarah R. I. Bennett, Woman’s Work Among the Lowly

James Dascomb to Mrs. Almira Barnes, October 26, 1843, OCA, Autograph File, RG 16/5/3

Albert Welles, History of the Buell Family of England

Henry Porter Andrews, The Descendants of John Porter of Windsor, Conn. 1635-9. Vol. 1

“Receipts of the Oberlin Board of Education”, Oberlin Evangelist, March 17, 1841

“Pocket sized subscription book”, OCA, RG 7/1/2, Subseries 7, Box 2, Envelope marked “[Probably Dawes book pages used as agent…]”

General Catalogue of Oberlin College: 1833- 1908

Robert Samuel Fletcher, A History of Oberlin College From its Foundation through the Civil War

James H. Fairchild, Oberlin: The Colony and the College, 1833-1883

George Derby and James Terry White, The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Volume XII

“Blakeslee Barnes House (1820)“, Historic Buildings of Connecticut

“Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount – 1774 to Present”, MeasuringWorth.com

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Welles, p. 224; “Receipts”; “Pocket-sized subscription books”; “Seven Ways”

[2] Barnes to Willard, June 28, 1844; Fletcher, p. 19; Dascomb to Barnes, Oct 26, 1843; General Catalogue, p. 333; Derby, p. 115; Welles, pp. 224-225

[3] Barnes to Willard, June 28, 1844; Lasser, p. 98

[4] Barnes to Willard, June 28, 1844

[5] Barnes to Willard, July 29, 1844

[6] Barnes to Willard, June 28, 1844; Barnes to Willard, Aug 12, 1844

[7] Barnes to Willard, June 28, 1844; Bristol to Hill

[8] Cazden, p. 56; Lasser, p. 12

[9] Cazden, p. 56

[10] Cazden, pp. 56-57

[11] Cazden, p. 57; Lasser, p. 96

[12] Lasser, pp. 96-97

[13] Bennett, p. 293