The Election of 1857 and Oberlin’s Dissent

Saturday, November 19th, 2016by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent, researcher and trustee

The recent Presidential election, in which Ohio continued its recent trend of flip-flopping between blue and red every 8 years, got me thinking about early Ohio history. It was even worse back then actually – with the flip-flops often happening every two years. In particular, I thought about the election of 1857, another biennial flip with accompanying flop, where the issues of the day were much more divisive than the issues we face today (as hard as that may be to believe!) The 1857 election would arguably turn out to be particularly significant to Oberlin, but it didn’t go Oberlin’s way at all. Nevertheless Oberlin would face the problem with characteristic steady and calm resolve, and ultimately Oberlin would prevail. (Note: This topic was originally covered in great detail in my Northern States’ Rights three-part series of blogs three years ago, but in light of recent events I thought it was worth revisiting from a new perspective with some additional information.)

The election of 1857 was a state election, not a national one. State elections were more significant then, as many Ohioans, including most Oberlinites, had given up on the federal government altogether and put their faith in the state to protect their rights. The federal government at that time seemed hopelessly wedded to the “slave power”, run by Democrats at a time when the Democratic party was unabashedly pro-slavery. The 1850s had seen an endless stream of intrusions by the Democratic “slaveocracy” on the liberties of the northern states and western territories, beginning with the notorious Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which denied accused fugitive slaves even the most basic legal rights and proscribed stiff penalties for anyone who assisted them, or even refused to assist in their capture. Even at the time of the 1857 election, Democratic President James Buchanan was doing everything in his power to force an oppressive pro-slavery state constitution and legislature on the overwhelmingly anti-slavery inhabitants of Kansas Territory.

But there was one ray of hope amidst all this angst for Ohio’s anti-slavery residents. In 1854, a new anti-slavery party called the Republicans had formed. And the statewide elections of 1855 saw an extraordinary flip where this brand new party took control of the governorship and both houses of the state General Assembly from the Democrats. Over the next two years, the Republican General Assembly passed four “personal liberty laws”, which partially counteracted the federal Fugitive Slave Law and restored some basic legal rights to Ohio’s black residents, hundreds of whom resided in Oberlin. The most radical of these laws, a “Habeas Corpus act”, was written by Oberlin’s own favorite son, Representative James Monroe, an Oberlin College Professor (see my Northern States’ Rights, Part 2 blog for details).

James Monroe (courtesy Oberlin College Archives)

All of this was in jeopardy, however, with the statewide election of October, 1857, as every state Representative and Senator was up for re-election. Without today’s sophisticated polling techniques (and yes, my eyes were rolling as I typed that), it’s hard to know exactly what the people of 1857 expected from the election, but clearly Oberlin hoped for another Republican victory and did its share by reelecting James Monroe to his seat. The rest of Ohio didn’t come through, however. There’s some indication of Republican complacency and low turnout, and some indication that the Democrats were particularly motivated to repeal the personal liberty laws, but whatever the case, the Democrats regained control of both houses of the General Assembly. (The Republican governor did manage to win reelection by a slim margin, but the governorship at that time was a relatively weak office, with no veto power.) [1]

If there was any adverse reaction in Oberlin to the election results, it’s not apparent from the historical record. Instead, James Monroe would return to his seat in Columbus and fight to keep Ohio Democrats from overturning the personal liberty laws, and Oberlin would quietly go about its usual business as if nothing had changed: assisting freedom seekers who appeared on its doorstep, and sending out abolitionist missionaries, teachers, preachers, journalists, lawyers, etc., to spread the anti-slavery message throughout Ohio and the northern states.

But elections have consequences, and the consequences of this one would be severe for Oberlin. Returning to his seat in Columbus in January, 1858, James Monroe, now a member of the minority party, knew he would face an uphill fight. The Democrats wasted no time in proving him right. Within days of their arrival at the capitol, they introduced a bill to repeal one of the Republican personal liberty laws, leaving no doubt that they intended to repeal the others as well and potentially turn Ohio’s citizens into “bloodhounds” for the “slaveocracy”. So Monroe addressed the Ohio House of Representatives and in his characteristic style issued the Democrats a stern warning:

When God created me, he set me erect upon two feet. I have never had any reason to doubt the wisdom of the arrangement. At least, I will never so far disown my own manhood, as to prostrate myself into a barking quadruped upon the bleeding footsteps of a human brother struggling to be free…

I believe you are pursuing a course well adapted to ruin your own party in the State, and restore the law-making power to the hands of the Republicans. When I came to the Legislature this Winter, I expected you to engage in a moderate share of Pro-slavery action; but this is an immoderate share of it… Even though, as a party, you should feel under the necessity of eating your peck of dirt, why should you – for that reason – volunteer to swallow a bushel? I have strong hope that you will not…

Some of the [news]papers in this part of the State, after the last election, complained, with good reason, that in some portions of the [Western] Reserve the Republicans did not turn out to the election. But gentlemen, if you will only pass this bill, and repeal the Habeas Corpus Act and the law to prevent slaveholding in the State of Ohio, and indorse Mr. Buchanan’s Kansas policy, there will be no complaint, two years hence, about the Republicans of the Reserve not turning out. The Yankees of Ashtabula, instead of staying at home to make cider on the second Tuesday of October, will leave the cider to work on its own account, and, thronging to the polls in a mass together with their fellow Republicans throughout the State, will, by triumphantly returning a majority to this General Assembly, rebuke this disposition to extend and fortify the slave power. [2]

Monroe’s mention of Ashtabula, a county in the staunchly abolitionist, far northeastern corner of the state, appears to have had some merit. “We are ashamed,” lamented an Ashtabula County correspondent the day after the election, “but we cannot help it. It rained hard nearly all day, and our lazy fellows could not be got out.” But the problem extended well beyond Ashtabula. [3]

Monroe also distributed a pamphlet urging the General Assembly not to repeal his own Habeas Corpus personal liberty law, describing a hypothetical situation that could play out without the protection that the personal liberty laws provided against the “unjust” and “hated” Fugitive Slave Law:

A law breathes its own spirit into all the proceedings under it. The deep hatred of the community, also, against an unjust law, often exhibiting itself in unmistakeable [sic] expressions of hostility, will sometimes justify, in the opinion of the officers of such a law, hasty and extraordinary proceedings. A United States marshal who should be sent to Greene County to seize a supposed fugitive, would be tempted, unless a man of uncommon courage, to enter the county in the night, seize the first colored man that he could find alone and unarmed, and leave before morning, without making any very extensive inquiry, as to whether he had taken the right man or not. [4]

The Democrats ignored Monroe’s warnings. They went ahead with their agenda and repealed three of the Republican personal liberty laws, leaving only the most conservative one standing. Not content with turning the clock back to 1854, they also took aim at an Ohio tradition that dated back sixteen years. “We are unalterably opposed to negro suffrage and equality, without reference to shade or proportion of African blood,” they proclaimed. Although Ohio’s state constitution had restricted voting rights to white men only from its very inception, the Ohio Supreme Court had ruled in 1842 that any mixed-race man who was “nearer white than black” was white enough to vote. Now in 1859, the Democratic General Assembly passed a law overturning that decision. [5]

As if that wasn’t enough, the federal government took the opportunity to pile on. Federal enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law had always been lax in the Western Reserve, and overt slavecatcher activity had been virtually non-existent in Oberlin for over a decade. Even in southern Ohio, President Buchanan had backed down from a confrontation with Ohio authorities over Monroe’s radical personal liberty law in 1857. But now that would all change. In the spring of 1858, while Ohio Democrats were earnestly repealing the Republican personal liberty laws, President Buchanan felt emboldened enough to appoint an aggressive new federal marshal named Matthew Johnson to the Northern District of Ohio. Johnson intended to go after fugitives from slavery not just in the Western Reserve, but specifically in Oberlin. To that end, he appointed a disgruntled Oberlin insider named Anson Dayton as his deputy. The election of 1857 was about to come home to Oberlin. [6]

Oberlin would stand firm, however. Dayton’s direct attempts to capture freedom seekers within the borders of Oberlin village in the summer of 1858 met with stiff resistance from Oberlin’s black community. By the end of summer he had grown more cautious, helping only to identify an alleged Oberlin fugitive named John Price to a visiting pair of Kentucky slavecatchers. It would be another U.S. marshal from Columbus who would join the Kentuckians in a duplicitous scheme to lure Price out of Oberlin, ambush him, and put him on a southbound train in nearby Wellington – actions eerily reminiscent of the hypothetical situation James Monroe had described just six months earlier. In an event that gained national notoriety as the “Oberlin-Wellington Rescue”, scores of Oberlinites rushed to Price’s assistance in Wellington. Although they succeeded in rescuing Price from his captors and escorting him safely to Canada, Oberlin and Wellington now found themselves in the crosshairs of an irate Buchanan Administration. A federal grand jury convened in Cleveland and indicted 37 men for violating the Fugitive Slave Law. [7]

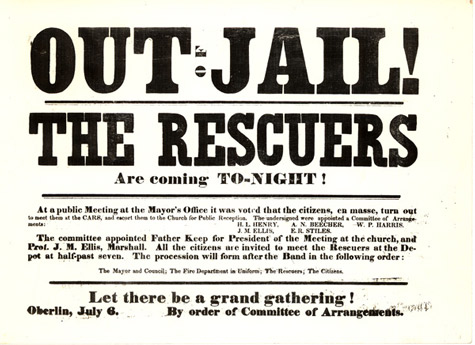

The Buchanan Administration could scarcely have made a more damaging move to their own cause, however. Oberlin, whose purpose from its inception as a colony was to “exert a mighty influence” on American spirituality, seized upon this event as an opportunity to exert a mighty influence on American public opinion regarding the “slave power” as well. After holding a defiantly jolly “Felon’s Feast”, the indicted men cheerfully turned themselves in to federal authorities, and as their trials dragged into April, 1859, they literally dared the federal government to jail them pending the verdicts, which the federal government compliantly did. [8]

It was a public relations bonanza. In Painesville, just a stone’s throw from Ashtabula County, a meeting of citizens “large in numbers, and earnest in spirit” responded two weeks later by passing the following resolutions:

Resolved, That the act of the Federal Court in causing the arrest and imprisonment of our fellow citizens of Lorain county, for no crime, but for the performance of a duty clearly required by Religion and Humanity, is an outrage…

Resolved, That the events now transpiring in Ohio, remind us of the duty of strenuous efforts for the return of a Legislature at our next election that will enact a Personal Liberty bill, providing for the political disfranchisement and outlawry of any citizen who shall in any way attempt the enforcement upon the free soil of Ohio of the hated Fugitive Law. [9]

The next month, thousands of Ohioans flocked to Cleveland, just blocks from where the Rescuers were being held in jail, to rally in support of the Rescuers and condemn the actions of the federal government. Republican Governor Salmon Chase addressed the angry crowd and reminded them: “The great remedy is in the people themselves, at the ballot box. Elect men with backbone who will stand up for [your] rights, no matter what forces are arrayed against [you].” [10]

Five months later, In the statewide election of October, 1859, Ohioans would do just that, fulfilling James Monroe’s prophesy of the year before. Not only the “Yankees of Ashtabula”, but “Republicans throughout the State”, left “the cider to work on its own account” and headed to the polls, “triumphantly returning a majority to this General Assembly.”

The Republicans returned with renewed energy and enthusiasm, but also tempered by their previous defeat. They would pass only one new personal liberty law* to join the lone personal liberty law that the Democrats were previously unable to repeal. (That unrepealed law, by the way, was instrumental in getting the charges dropped against the Oberlin-Wellington Rescuers.) The more radical personal liberty laws, like Monroe’s, the Republicans would leave on the shelf. But Ohio Republicans would also “demand the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.” The General Assembly did its part in accommodating that wish, electing Republican Salmon Chase, the country’s most vocal opponent of the Fugitive Slave Law, to the United States Senate (as U.S. Senators at that time were elected by state legislatures, not by popular vote). The Republican Ohio Supreme Court also pitched in, striking down the Democratic law of early 1859 that had denied the vote to any “persons having a mixture of African blood.” [11]

Republican enthusiasm flourished right on into the 1860 Presidential election, when Ohio elected by a wide margin the first ever Republican President, Abraham Lincoln. And the rest, as they say, is history.

But history repeats itself, as another saying goes, over and over again. Great progress is never linear, but a series of forward steps interrupted occasionally by the inevitable and often disheartening backstep. History teaches us that antebellum Ohio’s progress was no more linear than today’s – in fact far less so. But history also teaches us that progress can resume after a backslide, if its advocates use the opportunity to regroup and re-energize, to constructively “exert a mighty influence” on public opinion, to listen to the grievances of their opponents, and to accommodate those grievances that are reasonable while standing firm and courageous against those grievances that are not.

In the words of Mahatma Gandhi, “We may stumble and fall, but shall rise again; it should be enough if we did not run away from the battle.” [12]

* Historians have traditionally taken the stance that this General Assembly passed no new personal liberty laws – a claim that I myself repeated in my Part 3 blog. Since then I have discovered that the Republicans discreetly passed what amounted to a low-key personal liberty law in 1860. [13] This law would have an impact on the infamous Lucy Bagby case of 1861, and will be discussed in detail in a future blog.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

Ron Gorman, Kidnapped into Slavery: Northern States’ Rights, Part 1

Ron Gorman, Monroe’s Personal Liberty Law: Northern States’ Rights, Part 2

Ron Gorman, “Odious Business” in Oberlin: Northern States’ Rights, Part 3

James Monroe, “Speech of Mr. Monroe of Lorain, In the House of Representatives, Jan 12, 1858”, Oberlin College Archives, RG30/22, Series 5, Subseries 3, Box 27

James Monroe, Speech of Mr. Monroe of Lorain, upon the bill to repeal the Habeas Corpus Act of 1856

“The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue 1858“, Oberlin Heritage Center

Jacob Rudd Shipherd, Oberlin Wellington Rescue

Steven Lubet, The “Colored Hero” of Harper’s Ferry

Stephen Middleton, The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio

“Public Voice of the People. Public Meeting at Painesville”, Cleveland Daily Leader, Apr 28, 1859, p. 2

“Benighted Ashtabula”, Ohio State Journal, Oct. 16, 1857, p. 2

The Ohio Platforms of the Republican and Democratic Parties, from 1855 to 1881 Inclusive

Joseph Patterson Smith, History of the Republican Party in Ohio, Volume 1

“Alfred J. Anderson v. Thomas Milliken and Others”, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Ohio, Volume 9

Acts of the State of Ohio, Volume 57

James H. Fairchild, Oberlin: The Colony and the College, 1833-1883

Gaye Williams Ortiz and Clara A. B. Joseph, Theology and Literature: Rethinking Reader Responsibility

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Gorman, Part 3

[2] Monroe, “Speech…Jan 12, 1858”, pp.4, 7-8

[3] “Benighted Ashtabula”

[4] Monroe, Speech…Habeas Corpus Act of 1856, p. 5

[5] Ohio Platforms, p. 9; Middleton, pp. 130-131

[6] Lubet, pp. 58, 65, 77; Gorman, Part 3; Gorman, Part 2

[7] Gorman, Part 3; The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue 1858

[8] Fairchild, p. 19 (quoting John J. Shipherd)

[9] “Public Voice”

[10] Shipherd, p. 255

[11] Gorman, Part 3; Smith, p. 91; “Alfred J. Anderson”, p. 458

[12] Ortiz, p. 126

[13] Acts…Volume 57, pp. 108-109