Monroe’s Personal Liberty Law: Northern States’ Rights, Part 2

Saturday, December 28th, 2013by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent

It was May 27, 1857, four years before the start of the American Civil War. On this day an armed confrontation over the issue of states’ rights would occur between forces of the United States federal government and local law enforcement officers at South Charleston. But this wasn’t South Charleston, South Carolina, it was South Charleston, Ohio, about midway between Columbus and Dayton. The confrontation, which involved the exchange of gunfire and the serious injury of a county sheriff, would be called the “Battle of Lumbarton”, or the “Greene County Rescue”. A United States District Judge would blame the fighting on a “strange and anomalous” law passed a year earlier by the Ohio General Assembly. That law was written by Oberlin College Professor James Monroe, a freshman state legislator, with the support of Governor Salmon P. Chase. It was a “personal liberty law”, designed to counteract the effects of the 1850 federal Fugitive Slave Law (see my Kidnapped into Slavery blog post). But its critics would call it “shocking in its hideousness, loathsome in its practices, and dangerous in its designs.” This blog will examine that law and the battle that ensued. [1]

On its surface, there was nothing about this law that would suggest the “hidden treachery” its critics accused it of. Certainly nothing about its name would evoke anything but a deep yawn: “An act further to amend and supplementary to an act entitled an act securing the benefits of the writ of habeas corpus.” Nor was its author, Professor Monroe, the kind of fire-eating hot-head who you might expect would write a “statute of sedition and discord.” [2]

In fact this law, as its tortuous name suggests, was an amendment to an existing state law – the 1811 “act securing the benefits of the writ of habeas corpus.” The writ of habeas corpus is an ancient and revered legal custom that allows a judge to order a prisoner who is being detained to be brought before him so that the judge can determine if the detention is lawful. If the judge decides it isn’t, the prisoner is released. The writ of habeas corpus became a flashpoint in the late 1850s when northern states began to resist the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law and question the legality of the detentions of accused fugitive slaves held in custody by the federal government. [3]

In one particularly high-profile Ohio case, the 1856 Margaret Garner tragedy (see my Lucy Stone and the Margaret Garner tragedy blog post), a local judge issued a writ of habeas corpus to bring before him the Garner family, who were being held as alleged fugitive slaves, but they were returned to slavery instead. This infuriated Ohio’s abolitionist Governor, Salmon P. Chase, who found himself powerless to do anything about it. So Chase asked James Monroe to draft an amendment to the 1811 law that would give him the power to forcefully execute the writ of habeas corpus if the need were ever to arise again in the future. The result was the law described above, which is commonly known as the 1856 Habeas Corpus Act, or Monroe’s Personal Liberty Law. [4]

In the late 1850s, when Monroe was defending his law against critics who called it “a disgrace to our State” and demanded its repeal, he tried to downplay its radical nature, saying: “The late law amends and repeals only one section of the original act, and the amendment in this case is an unimportant one.”[5] But thirty years later he was singing a different tune. Here’s how he described his law to an Oberlin audience at that time:

The effective provision of the new bill was that whenever any judge or a State court who is about to issue the writ of Habeas Corpus for the relief of any person alleged to be unlawfully deprived of liberty by an officer, shall become convinced, by affidavit or otherwise, that such officer will not obey the writ, he shall direct it to the sheriff of the county, who shall proceed with the “power of the county” that is, all the able-bodied citizens of the vicinage, and take the person detained out of the custody of the officer detaining him, and bring him before the judge issuing the writ…

It is easy to see that any county like Lorain, where the anti-slavery sentiment was strong, would furnish a pretty lively company to be the sheriff’s posse. Neither slavery, nor the Fugitive Slave Law, nor even the United States Courts were named in the bill, but it was nevertheless a vigorous procedure. The bill had not much growl or bark in it, but it had plenty of teeth. [6]

Aha! So it wasn’t “unimportant” after all. It was a “vigorous procedure” with “plenty of teeth”. When you consider that the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law effectively made the federal government slavecatcher-in-chief, and that it prohibited federal officers who were holding alleged fugitive slaves from letting them go free, it can be seen that this law could indeed lead to armed conflict between the federal government and a “sheriff’s posse” made up of “all the able-bodied citizens” of an anti-slavery community. In fact, it could be called a state-sponsored rescue!

So let’s look at how it played out in the Battle of Lumbarton. The action began on May 27, 1857 in Mechanicsburg, Ohio, when a U.S. Deputy Marshal and his posse arrested four citizens for violating the Fugitive Slave Law by allegedly helping a fugitive slave to escape. The Marshal and his posse then headed out cross-country with their prisoners towards Cincinnati.

Word spread rapidly of the arrest, and a county judge issued a writ of habeas corpus ordering the county sheriff to bring the prisoners before him, so he could determine if the arrest was lawful. The Clark County Sheriff, John Layton, gathered a posse and went after the Marshal and his prisoners. They caught up with them near South Charleston. Gunshots were fired, but apparently nobody was hit. Sheriff Layton, however, was severely beaten during the altercation by the U.S. Marshal and his posse. The Marshal then continued on his way, with his prisoners, while the seriously injured Sheriff was attended to by his comrades.

Word spread once again, and a larger posse was gathered to pursue the Marshal as he and his entourage crossed into Greene County. This posse was led by Sheriff Lewis, who caught up with his quarry near Lumbarton (a.k.a. Lumberton). This time the U.S. Marshal surrendered without injury. Sheriff Lewis took the Marshal and his posse to Springfield and jailed them there for the assault on Sheriff Layton. The Marshal’s prisoners (the four Mechanicsburg men who had been arrested for helping a freedom seeker escape from slavery) were taken before a Judge in Urbana, who released them.

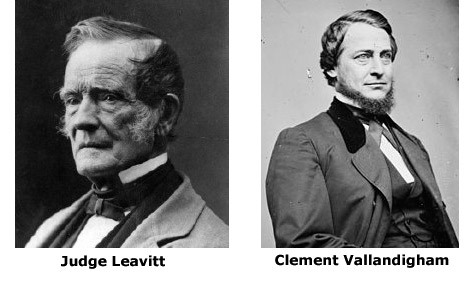

The case of the U.S. Marshal and his posse, held in jail in Springfield, now came to a hearing before a United States District Judge, Humphrey Leavitt. Arguing in favor of the Marshal was attorney and politician Clement Vallandigham, a Democrat. Arguing against the Marshal was Ohio Attorney General Christopher Wolcott, a Republican.

But the case quickly evolved into something much bigger in scope as Vallandigham launched into an excoriating attack on James Monroe’s 1856 Habeas Corpus Act, which he claimed was responsible for the violence:

The heat of the times demanded something of a higher mettle; and the act of 1856 is produced from the same loins, and engendered in the same spirit, but an offspring of far lustier and more vigorous birth. This act requires the writ [of habeas corpus] in certain cases to be addressed to the Sheriff or Coroner, even where the party is in custody of an officer by virtue of judicial process. It is therefore a hybrid – a monstrosity in legislation and jurisprudence… It is not a habeas corpus, because it is not addressed to the party who detains the prisoner… But it is called a habeas corpus, because that is a holy name and embalmed in the hearts of the people. It has a wicked and treasonable purpose to subserve, and it must assume a sacred name and garb… But the motives and the results expected from it cannot be thus concealed; and, in a court of law, it must be stripped of its disguises, and set forth in its true character – a statute of sedition and discord. [7]

Judge Leavitt basically agreed with Vallandigham and ordered the release of the U.S. Marshal and his posse. He also denounced Monroe’s Personal Liberty Law as being the cause of the violence:

To understand the nature of this conflict, it should be remembered that the deputy marshals, by their official oaths, were under a positive and paramount obligation to retain their prisoners, and to oppose all attempts to rescue them… The sheriff had a writ which commanded him to take the prisoners from the custody of these officers of the United States. It was not the usual and well-known writ of habeas corpus, … but a writ requiring them to be taken, forcibly, if necessary, from those having the prior and lawful custody… So the sheriff understood it; and hence he and his assistants deliberately armed themselves, as a preparation for the conflict which they foresaw was inevitable…

… the writ under the extraordinary Ohio law of 1856, requiring the officer to whom it is directed to take the prisoners, no matter by whom or by what authority they are detained, is a wholly different thing. This act seems to have been inconsiderately passed, and in its practical execution must lead to frequent conflicts between the national and state authorities. It might, with great propriety, be designated as an act to prevent the execution of laws of the United States within the state of Ohio. [8]

It bears mentioning that Judge Leavitt acknowledged that “it cannot be assumed as a fact” that the judge who issued the writ of habeas corpus knew that the prisoners were in the custody of a U.S. Marshal, leading James Monroe to argue that it could not be “assumed as a fact” that the Sheriff was operating under the 1856 Habeas Corpus Act. Governor Chase also voiced dissatisfaction with Judge Leavitt’s ruling, saying that it “denied the right of the State to execute its own criminal process or civil process, where the execution interfered with the claims of masters under the fugitive slave law.” However Chase did eventually meet with President James Buchanan, a pro-Southern Democrat, and negotiate a compromise whereby the federal government and the state of Ohio would drop all charges against all participants. (Although Monroe’s Personal Liberty Law was actually intended to free alleged fugitive slaves, in this case it freed four people who were accused of assisting fugitive slaves.) [9]

Judge Leavitt’s attack of the 1856 Habeas Corpus Act would play a role in the state elections of 1857, as James Monroe noted that “it was freely scattered about upon our desks, like other electioneering documents.” The Democrats would regain control of both houses of the General Assembly, and among their first orders of business when they took office in early 1858 was to attempt to repeal Monroe’s Personal Liberty Law. Professor Monroe wrote an eloquent (and sometimes witty) speech in defense of his law, but the Democrats brought it to a vote without discussion, so the speech was never delivered. But I thought it might be nice, a century and a half later, to post some excerpts from that undelivered speech. In addition to downplaying the radicality of the law (as has already been quoted), he intended to say the following: [10]

I see nothing in the character of the Fugitive Slave Act or its officers, which should make unlawful imprisonment or restraint less probable under that act than under others. There is no reason, so far as I can discover, why the business of slave-catching should make one engaged in it so much more intelligent and so much more tender of the liberty of his fellow men than others would be, as to exempt him from all danger of acting without proper authority. I think a slave-catcher, even though fortified with the virtuous consciousness of being a Buchanan Democrat, would still be subject to human infirmity… Partial and oppressive laws are very apt to be executed in an illegal and oppressive manner. A law breathes its own spirit into all the proceedings under it…

The provisions of a Habeas Corpus Act will be sufficiently stringent in every country where the people are not slaves, to secure obedience to the Writ, and they will be made especially vigorous in times when some great usurpation is stalking through the land, and crushing personal liberty under its elephantine tread…

If I understand this decision, it virtually robs us of the Writ of Habeas Corpus altogether. If a man is only a United States officer he may seize whomsoever he pleases without any legal authority whatever, and all the Writs which our State courts can issue will be of no avail for the protection of the injured party because he is in the custody of a United States officer…

But I shall be told that Judge Leavitt is against the law of 1856. This I admit without hesitation, and I hope without alarm. I shall endeavor to console myself for the want of such an ally by the high authorities I have quoted, and the arguments I have employed…

If there is danger of conflict between the State of Ohio and the Federal Government, it is because that Government is not willing to be confined within its constitutional limits – because in its zeal for the interests of its Southern masters, it is willing to put in peril the liberty of the people. This course, if persisted in, undoubtedly will produce a “conflict.” Tyrants have always had occasion to complain that the people would not submit to be enslaved quietly…

We have been frequently told… that the act of 1856 is an act of nullification, and that its friends are nullifiers – enemies of the Constitution and the Union… They have spoken as if they had a sort of monopoly of the American eagle – as if they were on terms of particular confidence with that bird, and we were men of too unclean lips to invoke her name… Sir, no man shall outdo me in attachment to the American eagle. The truly national eagle – the eagle of Washington, and Jefferson, and Franklin, is a bird that I admire… But the eagle of the Buchanan Democracy is a bird of a very different species and of very different tastes… a bird of Stygian form and hue, with blood shot eye and discordant scream and hideous and unshapely proportions, burying her sharpened beak and talons in the bleeding back of a fleeing, ghastly, famished negro, and beating her dusky wings upon his shrunken sides. To such an eagle I freely acknlowledge I profess no allegiance. She shall never spread her wings upon the banner under which I march. I avow myself a traitor to such a symbol of authority; and to all the consequences of such an avowal, I will cheerfully submit. – James Monroe

(In the next and final blog of this series, we’ll see the fate of this law and Ohio’s three other personal liberty laws, and the dramatic impact these laws had on Oberlin.)

SOURCES CONSULTED:

James Monroe, Speech of Mr. Monroe of Lorain, upon the Bill to Repeal the Habeas Corpus Act of 1856

“Ex parte Sifford” [5 Am. Law Reg. 659]

James Monroe, Oberlin Thursday Lectures, Addresses, and Essays

Clement L. Vallandigham, SPEECHES, ARGUMENTS, ADDRESSES, AND LETTERS OF CLEMENT L. VALLANDIGHAM

“An act further to amend and supplementary to an act entitled an act securing the benefits of the writ of habeas corpus”, Acts of the State of Ohio, Volume 53, p. 61

“John E. Layton and the Greene County Rescue Case of 1857”, Springfield, Ohio Community Website – History of Clark County

“Battle of Lumbarton”, Ohio History Central

“Clark County Sheriff was felled by federal marshals”, Springfield News-Sun, June 2, 2013

Thomas D. Morris, Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North 1780-1861

Jacob William Shuckers, The Life and Public Service of Salmon Portland Chase

Catherine M. Rockicky, James Monroe: Oberlin’s Christian Statesman & Reformer, 1821-1898

FOOTNOTES:

[1] “John E. Layton”; “Ex parte Sifford”; Monroe, Speech, p. 4

[2] Monroe, Speech, p. 4; “An act”; Vallandigham, p. 145

[3] Morris, pp. 168-180

[4] Shuckers, pp. 172-174; Monroe, Thursday, p. 115

[5] Monroe, Speech, pp. 4, 10

[6] Monroe, Thursday, pp. 119-120

[7] Vallandigham, pp. 144-145

[8] “Ex parte Sifford”

[9] Monroe, Speech, p. 13; Shuckers, p. 182

[10] Monroe, Speech, pp. 5, 8-9, 12, 13, 14