Was Abolitionism a Failure?

Wednesday, February 4th, 2015by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent and researcher

Last week the New York Times published a blog posted by Jon Grinspan that asked the question, “was abolitionism a failure?” The author answered the question with the assertion that “as a pre-Civil War movement, it was a flop.” It probably won’t come as a great surprise to anybody that the Oberlin Heritage Center doesn’t necessarily share that view, but I thought I’d take this opportunity to reply to some of the specific issues raised in that blog, and to let one of Oberlin’s most esteemed historical figures reply to the question in general.

The basic premise of Mr. Grinspan’s blog is that abolitionism was unpopular before the Civil War, and it was only the war itself that turned Northern public opinion decidedly against slavery. To demonstrate the unpopularity of abolitionism, the blog points to the scant support for the country’s first national abolitionist political party, the Liberty Party, and to the meager 3,000 subscribers to The Liberator, which the blog refers to as “the premier antislavery newspaper.”

Mr. Grinspan is indeed correct that the abolitionist Liberty Party, which existed in the 1840s, only garnered a paltry number of votes (6,797 in the 1840 Presidential election). But it should be remembered that prior to the Civil War many abolitionists were opposed to political action altogether, and very few advocated nationwide abolition by the federal government. Instead, the majority of abolitionists looked to “moral suasion” to convince the public that slavery was wrong, believing that government action, to the extent it was necessary, would naturally follow the shift in public opinion. This position was explained in 1835 in the Anti-Slavery Record, published by the American Anti-Slavery Society (which by 1840 would have almost 200,000 members): [1]

The reformation has commenced, both at the North and at the South. The more the subject is discussed, by the pulpit, by the press, at the bar, in the legislative hall and in private conversation, the faster will the change proceed. When any individual slave holder is brought to believe that slavery is sinful, he will immediately emancipate his own slaves. When a majority of the nation are brought to believe in immediate emancipation, Congress will, of course, pass a law abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. When the people of the several slave states are brought upon the same ground, they will severally abolish slavery within their respective limits. [2]

However, in the closing years of the 1840s the threat of slavery’s expansion caused many abolitionists to take a more active role in politics. The old Liberty Party was dissolved and was supplanted by the Free Soil Party, which received exponentially more votes, and which in turn was supplanted by the Republican Party, which took control of the Presidency, the House of Representatives, and most Northern governorships by 1860. And while the Free Soil and Republican parties were pragmatic political coalitions in contrast with the purely abolitionist Liberty Party, they both espoused opposition to slavery as their core issue. The 1860 Republican Party platform contained 7 (out of 17) planks that directly advocated anti-slavery principles and policies. To be sure, it also included a states’ right plank leaving the legality of slavery to the individual states to determine for themselves, but the 1844 Liberty Party platform left slavery to be “wholly abolished by State authority” as well. Pledging federal non-interference with slavery in the states where it already existed was a sentiment shared by the vast majority of abolitionists throughout the antebellum period, and was in no way an attempt to “abolish abolitionism”, as the blog describes it. [3]

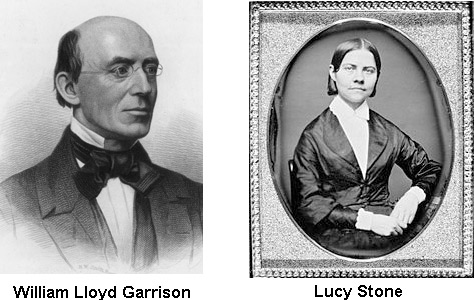

As for the characterization of The Liberator as “the premier antislavery newspaper”, this is also taking a partial snapshot of the early abolitionist movement and applying it to the entire antebellum period. The Liberator, published in Boston and edited by William Lloyd Garrison, was arguably the premier antislavery newspaper in 1831 when it was first published. (See my William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass debate in Oberlin blog.) But its strident disunionist, “no government” message, despite grabbing national attention, was too radical to ever develop a large subscribership, even as scores of anti-slavery newspapers proliferated throughout the Northern states over the next 3 decades, including The National Era (with a peak subscription base of 28,000), Frederick Douglass’ Paper, the Tappan brothers’ American Missionary (which was “read by twenty thousand church members”), and Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune (with a peak weekly circulation of 200,000). Ohio had numerous anti-slavery newspapers of its own, including the radical Garrisonite Anti-Slavery Bugle (with Oberlin College student Lucy Stone as a correspondent), the Cleveland Morning Leader, and the Oberlin Evangelist (which itself had a peak subscribership of over 4,300). Thus by the start of the Civil War hundreds of thousands of Northerners were subscribing to unabashedly anti-slavery newspapers. So it’s no wonder that William Lloyd Garrison, despite his own newspaper’s scant subscription base, could declare in 1860 that “a general enlightenment has taken place upon the subject of slavery. The opinions of a vast multitude have been essentially changed, and secured to the side of freedom.” [4]

But even in the lean years of the 1830s and early 1840s, abolitionists had enough clout to make a significant impact. In 1835 they launched a mass mailing campaign, sending hundreds of thousands of anti-slavery publications to clergymen and prominent leaders nationwide. Southern slaveholders felt so threatened by this campaign that they began a program of postal censorship, with South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun advising them to “prohibit the introduction or circulation of any paper or publication which may, in their opinion, disturb or endanger the institution” of slavery. Even President Andrew Jackson, himself a slaveholder, asked Congress in his Annual Message to censor the mail “in the Southern states”. Some of the less politically inhibited early abolitionists also flooded Congress with tens of thousands of anti-slavery petitions – so many that slaveholders tried unsuccessfully to prohibit (“gag”) anti-slavery petitions in the Senate and did succeed in gagging them in the House of Representatives from 1836 to 1844. [5]

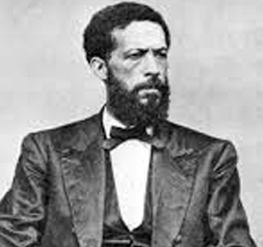

Although the leaders of the South did indeed manage to squelch the abolitionists in the southern states, their assault on free speech and constitutional rights only served to strengthen the abolitionist message in the North, where many Southern-born abolitionists emigrated and added their voices to the chorus. (See my William T. Allan – Lane Rebel from the South blog.) One of these was Oberlin’s John Mercer Langston, born in Virginia to an emancipated slave, sent to Ohio in his youth to escape the growing racial repression in the South, and educated at Oberlin College. On August 2, 1858, now a successful attorney and political leader, Langston delivered a “very stirring and excellent” speech to a Cleveland audience describing his impressions of the American abolitionist movement. Here are some excerpts: [6]

The achievements of the American anti -slavery movement since that time have been such as to impart hope and courage to every heart. Of course, I do not refer to the achievements of any separate and distinct organization. I refer to the achievements of that complicated and stupendous organization composed of persons from all parts of this country, whose aim is the abolition of slavery and the enfranchisement of the colored American. What, then, are some of its accomplishments? In the first place, it has brought the subject of slavery itself distinctly and prominently before the public mind. Indeed, in every nook and corner of American society this matter now presents itself, demanding, and in many instances receiving, respectful consideration. There is no gathering of the people, whether political or religious, which is not now forced to give a place in its deliberations to this subject. Like the air we breathe, it is all-pervasive. Through this widespread consideration the effects of slavery upon the slave, the slaveholder, and society generally, have been very thoroughly demonstrated ; and as the people have understood these effects they have loathed and hated their foul cause. Thus the public conscience has been aroused, and a broad and deep and growing interest has been created in behalf of the slave.

In the next place, it has vindicated, beyond decent cavil even, the claim of the slave to manhood and its dignities. No one of sense and decency now thinks that the African slave of this country is not a man…

More than this, the anti-slavery movement has brought to the colored people of the North the opportunities of developing themselves intellectually and morally. It has unbarred and thrown open to them the doors of colleges, academies, law schools, theological seminaries and commercial institutions, to say nothing of the incomparable district school. Of these opportunities they have very generally availed themselves; and now, wherever you go, whether to the East or the West, you will find the colored people comparatively intelligent, industrious, energetic and thrifty, as well as earnest and determined in their opposition to slavery… In the State of Ohio alone thirty thousand colored persons are the owners of six millions of dollars’ worth of property, every cent of which stands pledged to the support of the cause of the slave. Animated by the same spirit of liberty that nerved their fathers, who fought in the Revolutionary war and war of 1812, to free this land from British tyranny, they are the inveterate and uncompromising enemies of oppression, and are willing to sacrifice all that they have, both life and property, to secure its overthrow. But they have more than moral and pecuniary strength. In some of the States of this Union all of their colored inhabitants, and in others a very large class of them, enjoy the privileges and benefits of citizens. This is a source of very great power…

Another achievement of the American anti-slavery movement is the emancipation of forty or fifty thousand fugitive slaves, who stand to-day as so many living, glowing refutations of the brainless charge that nothing has, as yet, been accomplished…

But the crowning achievement of the anti-slavery movement of this country is the establishment, full and complete, of the fact that its great aim and mission is not merely the liberation of four millions of American slaves, and the enfranchisement of six hundred thousand half freemen, but the preservation of the American Government, the preservation of American liberty itself. It has been discovered, at last, that slavery is no respecter of persons, that in its far reaching and broad sweep it strikes down alike the freedom of the black man and the freedom of the white one. This movement can no longer be regarded as a sectional one. It is a great national one. It is not confined in its benevolent, its charitable offices, to any particular class; its broad philanthropy knows no complexional bounds. It cares for the freedom, the rights of us all… [7]

John Mercer Langston

Of course Langston would be among the first to tell you that race relations in the North were far from perfect in 1858, but they had clearly come a long way since the advent of The Liberator and the Liberty Party. As a gauge of just how far they had come, consider this: in 1837, an abolitionist journalist named Elijah Lovejoy was murdered by a mob in Alton, Illinois, for expressing anti-slavery sentiments. Two decades later, in October 1858, an Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln took the podium in that same town and said this:

I have said, and I repeat it here, that if there be a man amongst us who does not think that the institution of slavery is wrong in any one of the aspects of which I have spoken, he is misplaced, and ought not to be with us…

Has anything ever threatened the existence of this Union save and except this very institution of slavery? What is it that we hold most dear amongst us? Our own liberty and prosperity. What has ever threatened our liberty and prosperity, save and except this institution of slavery? If this is true, how do you propose to improve the condition of things by enlarging slavery,-by spreading it out and making it bigger? You may have a wen or cancer upon your person, and not be able to cut it out, lest you bleed to death; but surely it is no way to cure it, to engraft it and spread it over your whole body. That is no proper way of treating what you regard a wrong. You see this peaceful way of dealing with it as a wrong,-restricting the spread of it, and not allowing it to go into new countries where it has not already existed…

It is the eternal struggle between these two principles – right and wrong – throughout the world. They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time, and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity, and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says, “You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.” No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle. [8]

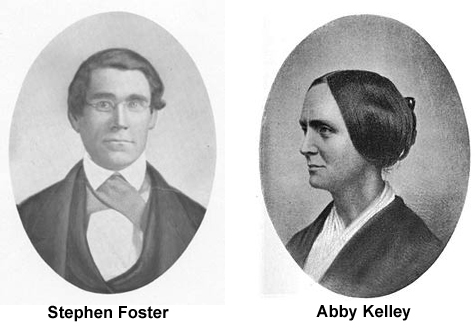

But far from being lynched, Lincoln was applauded for these words in 1858, and this and similar speeches gained for him the national recognition that would help elect him to the Presidency two years later. It was the heroic efforts of people like Elijah Lovejoy, John Mercer Langston, William Lloyd Garrison, Lucy Stone, and thousands of other abolitionist teachers, preachers, lecturers, authors, journalists, politicians, Underground Railroad agents, and parents (many of them educated at Oberlin College) that made that possible.

Elijah Lovejoy monument – Alton, Illinois

Just six weeks after Lincoln’s election, South Carolina would secede from the Union, stating as the cause that the Northern states had “united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery” and who believed that “the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction.” [9]

As it turns out, it was. The attempt to avoid that reality via secession only served to hasten its demise.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

Jon Grinspan, “Was Abolitionism a Failure?“, New York Times, January 30, 2015

John Mercer Langston, “The World’s Anti-Slavery Movement; Its Heroes and its Triumphs”

Abraham Lincoln, “Last Joint Debate at Alton; Mr. Lincoln’s Reply”

The Anti-Slavery Record, Vol 1, No. 1, January 1835

“Republican Party Platform of 1860“, The American Presidency Project

“Free Soil Party Platform (1848)“, Teacher’s Guide Primary Source Document Collection

“1844 Liberty Party Platform“, Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project

“The Declaration of Causes of Seceding States“, Civil War Trust

William Lloyd Garrison, The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison: From disunionism to the brink of war, 1850-1860

John C. Calhoun, Speeches of John C. Calhoun. Delivered in the Congress of the United States from 1811 to the present time

James D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, 1789-1907, Volume 3

William Cheek and Aimee Lee Cheek, John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1829-65

“1840 Presidential Election Results“, Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

Robert S. Fletcher, A History of Oberlin College from its Foundation through the Civil War

Stanley Harrold, The Abolitionists & the South

“About New-York Tribune“, Library of Congress

“Blacks and the American Missionary Association“, The United Church of Christ

“American Anti-Slavery Society“, Encyclopaedia Britannica

All photos public domain.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] “1840 Presidential Election”; “American Anti-Slavery Society”

[2] Anti-Slavery Record

[3] “Republican Party”; “Free Soil Party”; “1844 Liberty Party”

[4] Harrold, p. 142; “Blacks”; “About New-York”; Fletcher, Chapter XXVII; Garrison, p. 698

[5] Calhoun; Richardson, p. 176

[7] Langston

[8] Lincoln