Thomas Tucker and Charles Jones: Missionaries FROM Africa

Friday, November 22nd, 2013by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent

It’s no secret that one of the primary goals of Oberlin College in its first decades of existence was to train Americans to become missionaries who would go out into the world and crusade against slavery and other moral ills. That’s why I find the story of Thomas DeSaille Tucker and Charles Jones so intriguing; it’s an interesting twist on the traditional Oberlin narrative. Tucker and Jones were native Africans who came to America, attended Oberlin College and devoted their lives to combating slavery right here in the United States, serving as missionaries in the American South in its hour of greatest need.

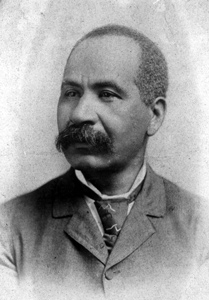

Thomas DeSaille Tucker

Courtesy State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory

Unfortunately I have no picture to post of Charles Jones, and the information on him is scant, but what we do have comes from reliable sources. There is quite a bit of information available on Tucker, however, and his legacy continues to this very day (although his middle name is subject to a wide range of spellings, including deSaliere, DeSota, and De Selkirk).

Jones and Tucker were raised in Sherbro, Sierra Leone, Africa. Jones was the son of a powerful Muslim chief, and Tucker was the grandson of another powerful chief, who also happened to be a slave trader.[1] Both youths were educated in the Kaw-Mendi (a.k.a. Mende or Mendi) mission that was established on the western coast of Sierra Leone by American philanthropists in the 1840s. In fact the land for the mission was rented to them by Tucker’s grandfather, and the original purpose of the mission was to repatriate the survivors of the slave ship Amistad. Oberlin College benefactors Lewis and Arthur Tappan were among the main supporters of the mission, which was basically run by Oberlin students and alumni, about 30 of whom would ultimately serve there. Certainly Jones and Tucker would have known, and perhaps been influenced by, Sarah Margru Kinson, one of the original Amistad captives, who was educated at Oberlin College after her release, then returned to Sherbro in 1849 to become a missionary and teacher herself. (For more information on Sarah Margru Kinson, the Amistad, and the Mendi mission, see Sarah Margru Kinson: The Two Worlds of an Amistad Captive, by Marlene D. Merrill, available from the Oberlin Heritage Center gift shop.)

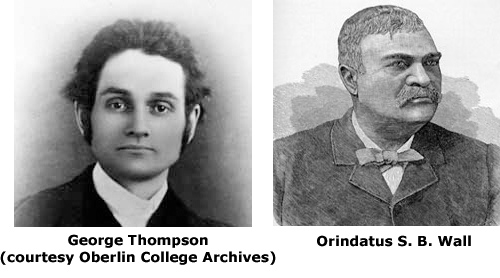

Jones and Tucker were brought to the United States in 1856 by Oberlin College alumnus George Thompson, who returned to Oberlin after relinquishing his post as director of the Mendi mission. Tucker would have been about 12 years old at the time, Jones was probably about 17. Interestingly, they arrived in the United States in the summer, and when asked how they liked it, they replied, “We like it very well, but it is too hot for us, we can’t stand it!”[2]

Both of the boys lived with Thompson initially, although Jones eventually took a shoemaker apprenticeship with Oberlin’s Orindatus S. B. Wall and moved in with his family. Tucker entered the preparatory school at Oberlin College in 1858 at the age of about 14, and entered the collegiate program two years later. Jones attended the preparatory school in the 1860-1861 school year. But both had every intention of returning to Africa after receiving their education, just as Sarah Margru Kinson had, to dedicate their lives, as Tucker put it, to “do good in my native land.”[3]

When Tucker was still in Africa as a 10 year old boy, he had written to Lewis Tappan about the “wicked practices” of his country, including warfare that involved attacking towns when “the enemy on the other part are asleep” and killing “their enemies so much even as not to have pity upon some of young babes.” A relative of Tucker’s, who would eventually become a slave trader himself, had also written Tappan that “slavery and bigamy or polygamy will be the last sins an african [sic] will forsake.” But now that Thomas Tucker had crossed the ocean, he came to see that the United States had its own sins and wicked practices, as he wrote to a friend back in Africa:

‘The colored men in this country have no voice in the general government; even in some of the States they have no voice in the State government. It would fairly sicken you to be here on a fourth of July and hear guns firing and “starspangled banner” waving “over the land of the free and the home of the brave” while there are this day 4,000,000 of slaves in their possession. O what a hypocrisy. God will not always sleep but will yet come in judgment against this country except they speedily repent.’[4]

Then the American Civil War broke out. Union forces made slow progress into the slaveholding states of the South, and as they did so they were thronged by slaves who had escaped from their owners. The Fugitive Slave Law, which remained in force, demanded that slaves be returned to their owners on claim. Although some Union commanders were all too happy to comply and relieve themselves of the burden of accommodating the freedom seekers, a few saw this as an opportunity to strike a blow against slavery and the Confederacy. General Benjamin Butler, who had seized the military bases at Fortress Monroe in the Norfolk-Hampton region of coastal Virginia, was among the latter. Arguing that the Confederates considered the slaves as “property” which they were using to support the rebellion, he claimed the right to refuse their return. And thus hundreds of freedom seekers became “contraband” of war.

Now came the tremendous logistical problem of sheltering them, feeding them, and providing them the education that most had been denied all their lives. Mary Peake, a local free black school teacher, and Peter Herbert, a local fugitive from slavery, got permission to establish schools on property seized by the Union forces. Herbert in fact established his school in the abandoned summer home of slaveholding ex-President John Tyler, who had left the area and thrown his support to the Confederacy. Both Peake and Herbert soon had dozens of students in their classes.

Northern abolitionists, both black and white, from the American Missionary Association (the same group that ran the Mendi mission) also came down to help. Reverend Lewis C. Lockwood directed relief operations in person and helped establish more schools, while George Whipple (one of Oberlin’s “Lane Rebels”) and Simeon S. Jocelyn petitioned the Lincoln Administration for support. On December 3, 1862, the Oberlin Evangelist reported:

“Since the meeting of the Am. Missionary Association in this place, Oct. 15, five students from Oberlin College and Seminary have left us for service under the Association in labors among the freemen at or near Fortress Monroe, or in South Carolina, namely: Wm O. King and Palmer Litts, of the Junior Theological Class; Edwin S. Williams of the Middle Theological Class and his wife; and Thomas De Selkirk Tucker of the Junior Class, a native of Sherbro, Africa, brought thence by Rev. Geo. Thompson and in a course of education in Oberlin College. They are all teachers of considerable experience, with the exception of the last named, and all give promise of efficiency and usefulness in their work. They left us with many requests for prayer – their case and work awakening profound sympathy among their Christian friends. Not having completed their course of study, they all expect to return for that purpose after a service perhaps of six months.”

Upon his arrival in Hampton, Virginia, Thomas Tucker immediately began teaching classes in the Tyler house. It was difficult work. The teachers were faced with overcrowded classrooms, they endured the hostility and prejudices of many of the Union troops as well as the local populace, and their varying backgrounds and skill levels sometimes created tensions among themselves. But the missionaries drew their inspiration from their students, finding “their love of freedom strong. Their desire for learning and the aptitude of children and adults to learn… remarkable.”[5]

Tucker returned to Oberlin in mid-1863. The time he spent in Virginia and the substandard pay he received while there set his Oberlin education back one year, but with cooperation of the school administration he was able to secure good winter employment and continue his education.[6]

In 1864, Tucker expressed disappointment that his Mendi friend, Charles Jones, had joined the Union armed forces. Tucker took this as a sign (quite correctly, it turned out) that Jones would not be returning to Africa. That Jones enlisted is not surprising, given that his Oberlin mentor, O.S.B. Wall, became a tireless recruiter of black Ohio soldiers when the Lincoln Administration finally allowed African Americans to enlist in 1863. (Wall himself earned a Captain’s commission, perhaps the first African American to do so.) Wall recruited for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Volunteer and the 5th United States Colored Troops (USCT) infantry regiments in 1863, and the 27th USCT infantry regiment in early 1864. Only one Charles Jones appears on the roster of these regiments, as a private in Company D of the 27th USCT, which recruited several African American men from Oberlin. If this was our Charles Jones, he would have seen some of the hardest fighting of the entire war in Virginia in the Spring and Summer of 1864.[7]

Tucker himself was still intent on returning to Africa after completing his Oberlin education, saying:

“Whenever I reflect, so far as youth can, on all the Providences connected with my coming to, and residence in this country, thus far, I cannot resist the conviction that he intends me for some work in life. To be sure all men know that they were not made to be drones; yet there are times when we are, as it were, divinely impressed with a sense of the path marked out for us in life. I feel that my only highest goodness and happiness will consist in spending my life for benighted dear Africa… At all events, unless I can see plainer indications of Providence allotting me a sphere of duty in this country, to Africa I will return.”[8]

However he also began to foresee difficulties if he returned to his powerful family in Sherbro, writing:

“Far from any desire to forget and foresake Africa; I still yet, as I have in the past, cherished the deepest sympathy for my native land… My family influences in the Sherbro, as you well know, are very extensive. Returning there I would be subjected to trials and temptations which you perhaps can not well conceive of in this country. As your Sherbro mission is the only one you have in Africa, and as I could not return and labor there without great disadvantages, I preferred to be where I could be most efficient. I could willingly go to such a place as Shengay, Sierra Leone — anywhere where I can be farthest from my relatives.”[9]

But when Tucker received his A.B. (Bachelor of Arts) degree from Oberlin in 1865, there were no teaching opportunities for him in Africa outside of the Sherbro mission. He thus resolved himself to be “governed by a sense of duty, and not by selfish inclinations” and to “teach in any capacity — for the elevation of the freedmen.”[10]

And that he did. After graduating, Tucker returned to the South, this time to educate freedmen in Georgetown, Kentucky and later New Orleans, Louisiana. His friend, Charles Jones, having survived the war, also heard the calling to head south and became a preacher in Mississippi. (He was believed to be in Friars Point, Mississippi until about 1883, and then sometime thereafter might possibly have relocated to North Carolina, still preaching.)[11] Tucker edited a series of newspapers while in New Orleans and studied law at Straight University, a school established by the American Missionary Association to train black missionaries and to provide legal training to students to help support civil rights in the South. (Straight University eventually merged into present-day Dillard University.) Tucker earned his law degree in 1883, then moved to Pensacola, Florida, where he had a successful law practice for four years.

In 1887, Tucker co-founded a college in Tallahassee, Florida called the State Normal School for Colored Students. His co-founder was another Oberlin College black alumnus and one-time Florida state legislator, Thomas Van Renssalaer Gibbs. When the State Board of Education selected Tucker to be the school’s first president, the editor of a local newspaper wrote:

“The State Board of Education certainly deserves much credit for the appointments recently made for this school. … We have known Professor Tucker for about 18 years and we have never met a more genial, broadminded and sterling gentleman. He possesses first-class qualities as a friend, gentleman and scholar, and commands the respect of all who know him. He is a strong man, morally and intellectually, and the new Normal has a security of success under his charge.”[12]

Tucker would serve as president for 14 years, but would eventually be forced to resign over policy differences with state authorities. Influenced by his own Oberlin College education, Tucker wanted the school to offer a strong liberal arts education to its students to complement its vocational training. State authorities believed the school should focus on vocational training only, and accused Tucker of providing instruction that was “void of the results of the kind for which the money was furnished” and of hiring instructors who were “not in sympathy… with Southern institutions.” Interestingly enough though, Tucker was replaced by yet another African American Oberlin College graduate, Nathan B. Young.[13]

According to his contemporary Florida historian, Rowland H. Rerick, Tucker was “an able and intelligent man, of excellent character and notable executive ability and an admirable influence upon the students.’’[14] But now he returned to his law practice and died just two years later in 1903. If he were with us today, however, he would undoubtedly be proud of the college he co-founded. No longer known as the State Normal School for Colored Students, it is now called the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (“Florida A&M”), and provides a wide range of studies and programs, from baccalaureate to doctoral, to students of all races and ethnicities, though predominantly African American. And yes, it provides liberal arts instruction too.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

Clara Merritt De Boer, The Role of Afro-Americans in the Origin and Work of the American Missionary Association: 1839-1877, Vols 1 & 2

Robert Francis Engs, Freedom’s First Generation: Black Hampton, Virginia, 1861-1890

Leedell W. Neyland, “State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Florida”, The Florida historical quarterly, Volume 43 Issue 02. October 1964, pp. 108-110

George Thompson, The Palm Land; Or, West Africa, Illustrated

“Teachers for the Freedmen”, Oberlin Evangelist, Dec 3, 1862, p.7

Joseph Yannielli, “George Thompson among the Africans: Empathy, Authority, and Insanity in the Age of Abolition”, Journal of American History, vol 96, issue 4, March 2010, p. 998

General catalogue of Oberlin college, 1833 [-] 1908, Oberlin College Archives

Robert Samuel Fletcher, A history of Oberlin College: from its foundation through the Civil War, Volume 1

Clifton H. Johnson, “Tucker, Thomas DeSaliere”, Dictionary of African Christian Biography

Oberlin College Archives, RG 28/1, Alumni and Development Records, Former Student File, Series B, Box 313, Folder “Jones, Charles 1860-1861”

1860 United States Census, Lorain County, Russia Township

National Park Service, “Soldiers and Sailors Database”

Ira Berlin, Joseph Patrick Reidy, Leslie S. Rowland, The Black Military Experience

William E. Bigglestone, They Stopped in Oberlin

Mark St. John Erickson, “An uneasy alliance of white missionaries and refugee slaves leads to freedom in Civil War Hampton”, HR History

Joe M. Richardson, Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861-1890

Adam Fairclough, “Being in the Field of Education and also Being a Negro…Seems…Tragic: Black Teachers in the Jim Crow South”, The Journal of American History, Vol. 87, No. 1. (Jun., 2000), pp. 65-91

Emma J. Lapsanky-Werner, Margaret Hope Bacon (editors), Back to Africa: Benjamin Coates and the Colonization Movement in America, 1848-1880

Marlene D. Merrill, Sarah Margru Kinson: The Two Worlds of an Amistad Captive

Abdul Karim Bangura, “The Life and Times of the Amistad Returnees to Sierra Leone and Their Impact: A Pluridisciplinary Exploration”, Africa Update Newsletter, Vol. XIX, Issue 2 (Spring 2012)

Versalle F. Washington, Eagles on their Buttons

Daniel J. Sharfstein, The Invisible Line

Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University

Anne W. Chapman, “Fight for Home Saves Plantation”, Daily Press

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Yannielli, p. 998

[2] Yannielli, p. 998; De Boer pp. 121-122; 1860 U.S. Census; Thompson, pp. 441-442

[3] Sharfstein, p. 94; 1860 U.S. Census; General Catalogue; Lapsanky-Werner, p. 152

[4] De Boer, pp. 119-121, 123

[5] Engs, p. 36, 48

[6] De Boer, pp. 258-259

[7] De Boer, p. 261; Washington, p. 13; Berlin, p. 93; Bigglestone, pp. 237-240; “Soldiers and Sailors Database”

[8] De Boer, p. 259

[9] ibid, p. 261

[10] ibid, pp. 260, 262

[11] Yannielli, p. 998; Oberlin College Archives, RG 28/1

[12] Neyland, p. 108; General Catalogue; Johnson, “Dictionary”

[13] Neyland, pp. 109-110; Yannielli, p. 998; General Catalogue

[14] Neyland, p. 110