Sandusky’s Underground Railroad

Tuesday, December 10th, 2019by Melva Tolbert, OHC Volunteer

About 4 years ago, the Oberlin Heritage Center traveled to Sandusky, Ohio as part of their education program for staff and volunteer docents. Unfortunately, I was unable to attend, but continued to have an interest in the history of Sandusky’s involvement with Underground Railroad and wanted to learn more. This past October, my husband and I ventured out and found two locations connected to this history: the Second Baptist Church and the Follett House Museum. The experience was memorable and I want to share it with all of you.

We found the Second Baptist Church (on Decatur St.), which is said to have been one of the most active locations in the Sandusky Underground Railroad network. We were fortunate to find one of its members at the neighboring parsonage and he invited us in for a brief tour of the current building. The historic placard in the front yard explained the Underground Railroad activity that occurred there. With the view of Lake Erie in plain sight from our location, it was easy for me to visualize the freedom seekers’ journey to Canada. The gentleman led us into the small sanctuary with its large stained glass windows and purple family pew cushions. The original church was founded as a Zion Baptist Church in 1849 by a group of formerly enslaved peoples and freeborn Blacks. Just prior to the Civil War, the church was organized at its present site under the name First Regular Anti-Slavery Baptist Church. The sanctuary that we stood in dates to around 1930, and was constructed around the original church’s wooden framework.

Second Baptist Church, March 17th 1957. Photo Courtesy of the Sandusky Library.

I asked whether there was a basement, which our guide confirmed there was, so we followed him downstairs to a large room with tables, chairs, and a large commercial kitchen. Our guide then showed me a side room that housed the furnace. Thinking about how the space may have been used in the era of slavery, I could image that many people seeking refuge could find some rest and comfort here before continuing on to Canada.

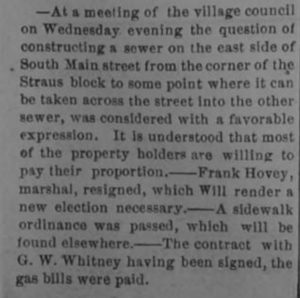

The following day, I arrived at the Follett House for a tour. The original use of the home was for Oran and Eliza Follett and their children. The home is now owned and operated by the Sandusky Public Library, which documents the history of both Sandusky and Erie County. My tour began in the den of Mr. Follett, who was known primarily for being a publisher, president of the Sandusky, Dayton, and Cincinnati Railroad, and for his involvement in the local banking industry. His wife was a homemaker and active in the local community providing aid to those in need.

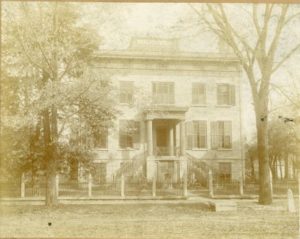

The Follett House, ca. 1984. Photo Courtesy of the Sandusky Library.

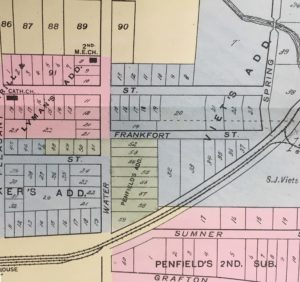

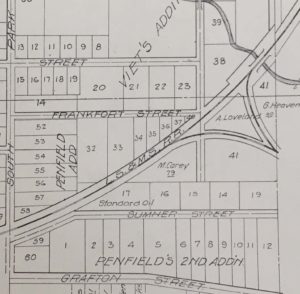

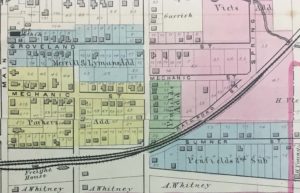

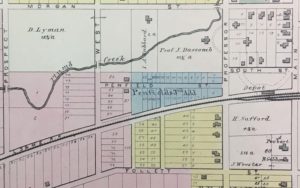

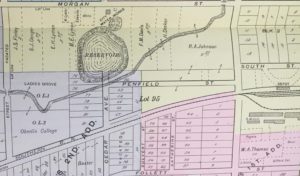

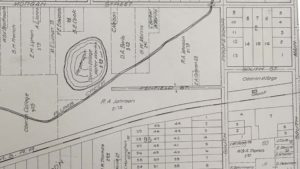

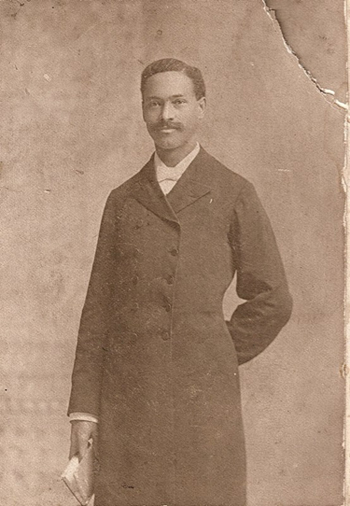

The docent led me to the front parlor and rear parlor pointing out the massive fireplaces which illustrated the family’s wealth. There was a temporary display in the rear parlor of people connected to Sandusky’s early Underground Railroad activity, including the Folletts. We then continued the tour into the basement of the home. There were several quilts displayed and old maps of the Sandusky area. The tour led us to the second floor which contained four large bedrooms for the family and then to another staircase to the fourth floor (attic) where the tour ended.

My desire is to continue visiting and learning more about this incredibly historic area of Ohio, and I urge all of you to do your own exploring as well.

For more information on the Sandusky Underground Railroad Network, feel free to visit the following websites to plan your own experiences: