Oberlin and Hair Depilatories

Wednesday, August 3rd, 2022By Emily Winnicki, 2022 Summer OHC Intern

DISCLAIMER: The Oberlin Heritage Center does not recommend the use of any products not currently approved by the FDA.

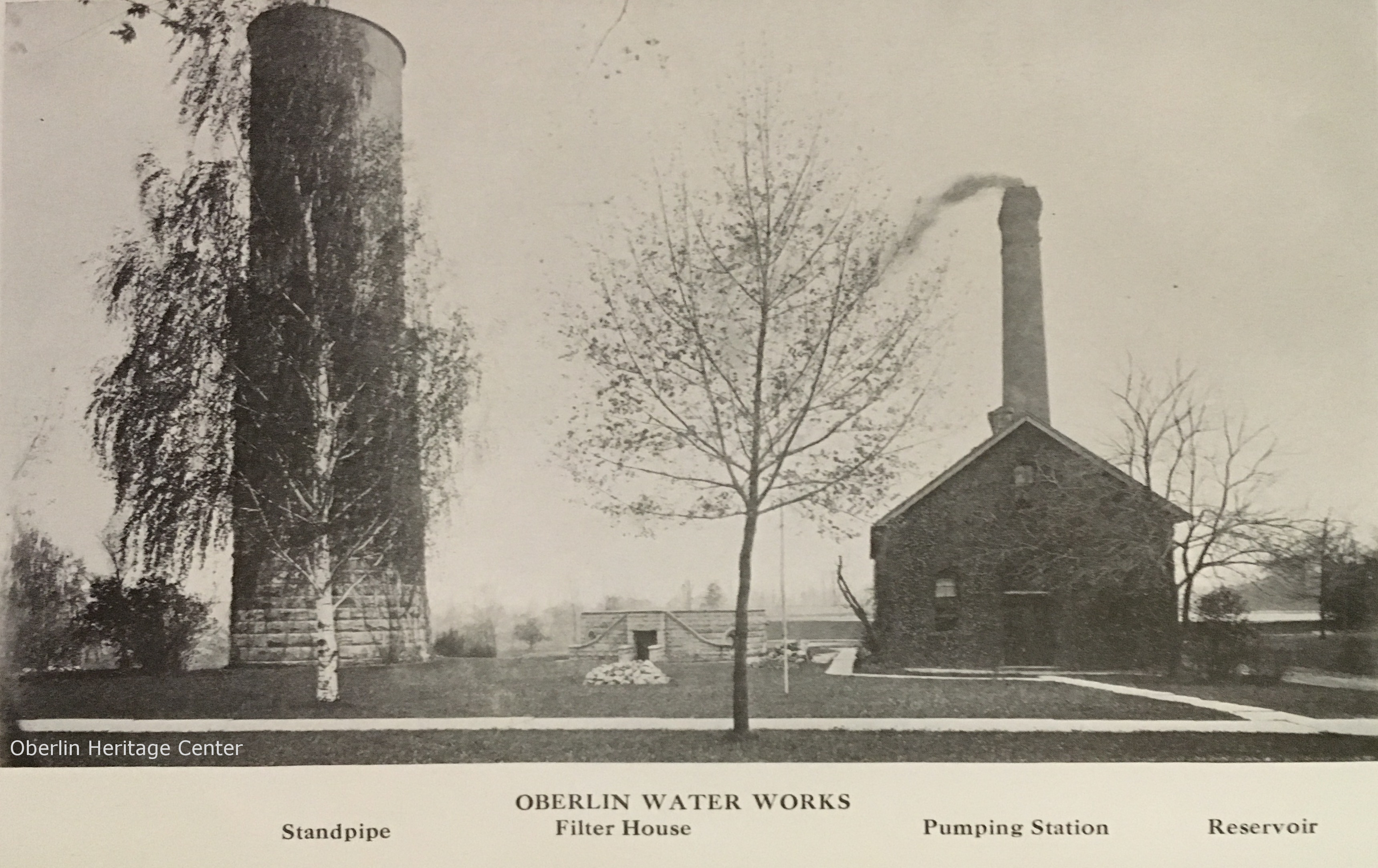

Figure 1. Advertisement for “Flash” (Oberlin Alumni Magazine, July 1921)

History of Hair Removal

The history of hair removal dates to prehistoric times, with cave drawings depicting men without facial hair. Ancient Egyptians removed hair from their faces and heads for the practical reason of limiting the enemies’ ability to seize them in battle. Early politicians in America stayed clean shaven, and it was not until Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1861 that there was a sitting President of the United States who had a beard. The history of removing hair on women dates back just as far, with portrayals of ancient women of Greece, Egypt, and the Roman empire removing all of their body hair. [1]

In 1844, Dr. Gouraud created one of the first marketed depilatories in the United States. In the past, people had used different solutions and creams or physical methods of shaving and plucking to remove hair, but Dr. Gouraud’s Poudre Subtile, translated as Subtle Powder, is often cited as the first depilatory [2]. By 1895, King Camp Gillette marketed the first safety razor featuring disposable blades. But it was not until 1915, thirty years later, that Gillette marketed a razor for women [3]. This shift, marketing razors and shaving supplies for women, reflects a change in fashion that took place at the beginning of the 20th century. By the 1920s, sleeveless tops and shorter dresses were becoming popular, so women felt the need to find ways to make their legs and armpits ‘smooth.’ Advertisements that targeted women used the term ‘smooth’ because ‘shaving’ was considered too masculine of a term [4]. Upon the rise of the Roaring Twenties, women saw a rise in hemlines, which occurred simultaneously with a rise in the number of advertisements for hair removal devices and creams specifically marketed towards women [5]. This is the era that sets the stage for Oberlin’s own, locally made depilatories.

Professor Jewett and “Flash”

As an intern at OHC this summer, I performed research on the achievements and legacy of Professor Frank Fanning Jewett. During the research, I came across a small reference to a depilatory which Professor Jewett had crafted. The idea of a locally made depilatory intrigued me. Through more digging, I found two locally produced depilatories, “Flash” and “Enzit.” These two depilatories had similar timelines and advertising techniques.

On April 20, 1921, a short article in the Oberlin News was titled “New Company at Work”. The Oberlin Chemical Company was starting to manufacture a depilatory which would be prepared using a formula crafted by Professor Frank Fanning Jewett. The article makes a point of noting that Professor Jewett had been the “head of the department of chemistry of Oberlin College” and also announces that the manager of the company is to be C. W. Upp [6]. Later that same year, in May of 1921, C.W. Upp is listed as the owner of the newly opening Campus View Beauty Parlor—located above Cooley’s Shoe store, and using the same stairway as Rice’s studio, which was located above today’s 37 West College Street. According to the article on the Campus View Beauty Parlor, “all the conveniences and services a woman can desire are found under one roof.” One of the noted services is the “application of the new depilatory, recently invented by Prof. Jewett” [7]. The use of the word ‘recently’ is interesting because in 1921, Prof. Jewett would have been 77 years old. So, this 77-year-old chemist was creating hair depilatories which were being advertised for women? It makes one wonder who, if anyone, is testing this product? His 67-year-old wife?

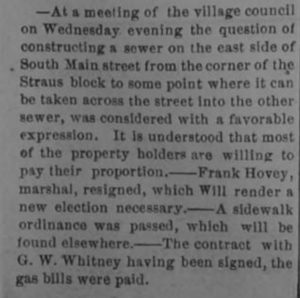

By July 1921, the Oberlin Chemical Co. was placing advertisements in the Oberlin Alumni Magazine.

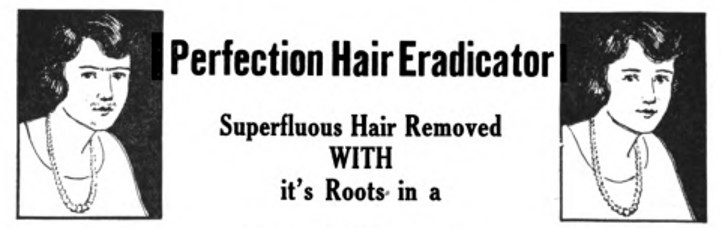

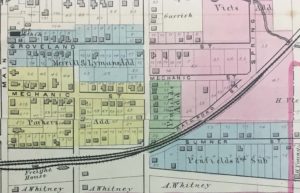

Figure 2. Advertisement for “Flash” (Oberlin Alumni Magazine, July 1921)

The viewer of this advertisement is immediately attracted to the name “Flash” surrounded by lightning bolts and the ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures. On the left side of the advertisement, there is a sketch of a woman who has “Superfluous Hair,” in the form of a slight unibrow, and some hair on her lip and chin. On the right side of the advertisement, there is a sketch of the same woman but with these ‘hairs’ removed. After reading the title and viewing the images, a person then continues down the advertisement, reading claims about how the depilatory is both safe and effective for removing the hair and the roots. At the end of the article the statement “a YALE graduate, the head of the Oberlin College Chemical Department for many years” is a reference to Professor Jewett. Finally, this advertisement provides an address for this new chemical company, 31 West College Street. While this address does not exist today, it was once used as the address for the upstairs of today’s 29 West College Street [8].

In October of 1921, an Annual Report filed by the Oberlin Chemical Company listed it as a new incorporation with finances amounting to $30,000 [9].

Shortly after the advertisement and annual report, in November 1921, an article in the Oberlin News tells of the sale of “exclusive sales rights in the United States” of “Flash” to Oberlin businessmen: Howard Askey, W.D. Hobbs, and Stanton Hobbs. These new owners of “Flash” were planning “an extensive advertising campaign and a little later will open a sales and demonstration office here in Oberlin.” This article concludes with a prediction of success for these new owners [10].

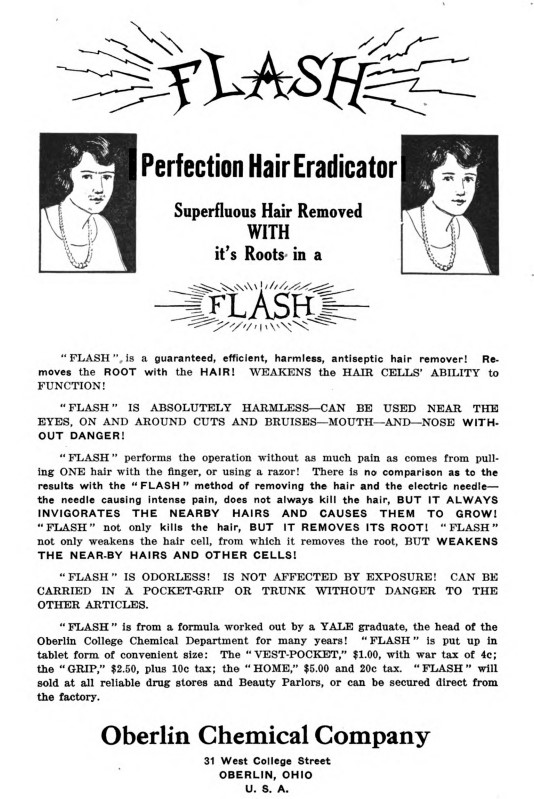

In May 1922, there was another advertisement for “Flash” in the Oberlin Alumni Magazine.

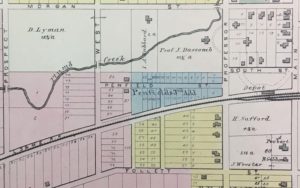

Figure 3. Advertisement for “Flash” (Oberlin Alumni Magazine, May 1922)

This advertisement is similar to the July 1921 advertisement, although, this one lacks the ‘before and after’ pictures, including only the ‘after’ sketch, and does not reference Professor Jewett. The lack of mention is possibly because Professor Jewett had sold his right to “Flash” by this point [11].

After 1922, I have found no mentions about “Flash” or the Oberlin Chemical Company and no patents can be found for “Flash.” [The owners could have decided to keep “Flash” as a trade secret instead of patenting the formula]. While the story of “Flash” ends in 1922, the story of another depilatory crafted in Oberlin picks up just four years later in 1926.

Philip Ohly and Enzit

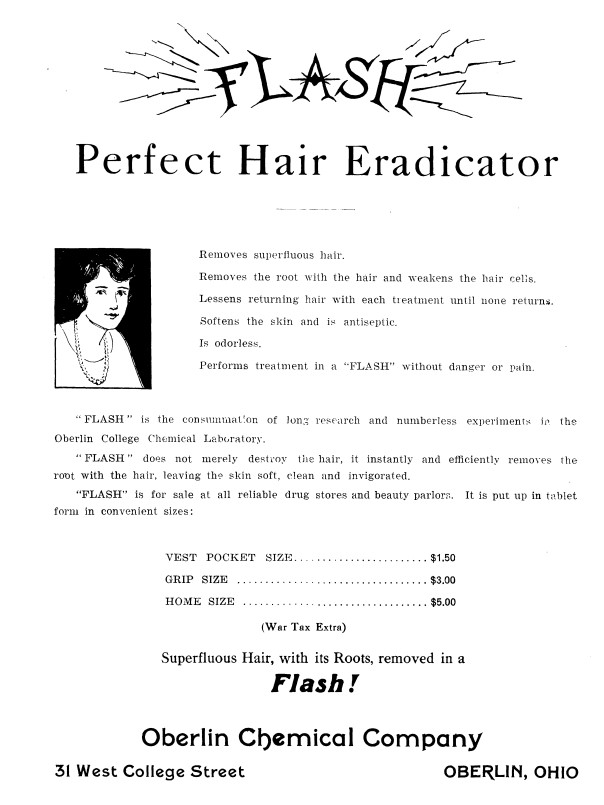

In the 1926 Index of U.S. Patents, one can find a listing for Philip H. Ohly, who “doing business as Enzit Chemical Co., Oberlin, Ohio” had received a patent for a depilatory on November 9, 1926 [12]. Also in November 1926, the Oberlin Alumni Magazine, ran an advertisement for “Enzit”.

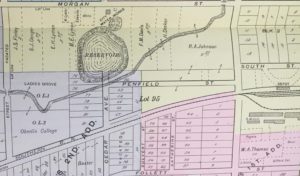

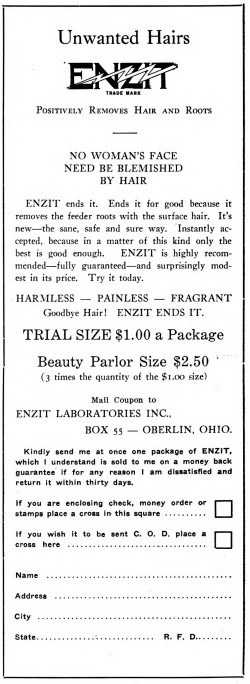

Figure 4. Advertisement for “Enzit” (Oberlin Alumni Magazine, November 1926)

This product is advertised as “A New Hair Remover that does Amazing things” by removing your unwanted hair and roots. In earlier pages of the Alumni Magazine, it mentions that Ohly had “perfected a formula for a depilatory” which he had been working on for several years [13].

In 1927, we find two advertisements for Enzit.

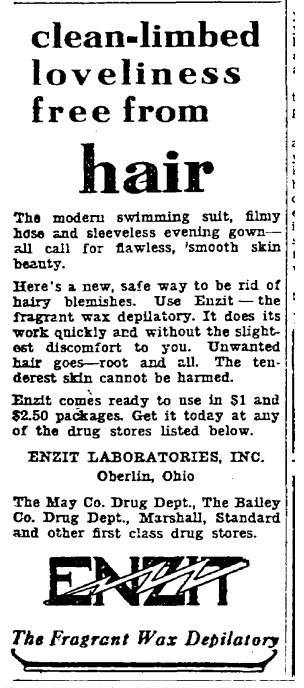

Figure 5. Advertisement for Enzit (Oberlin Alumni Magazine, January 1927)

Figure 6. Advertisement for Enzit (Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 5, 1927)

Similar to “Flash,” “Enzit” targets selling to women, because “No woman’s face need be blemished by hair” [14]. Claiming that “Enzit” will leave women with “smooth skin beauty” [15].

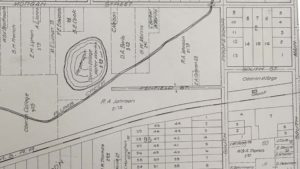

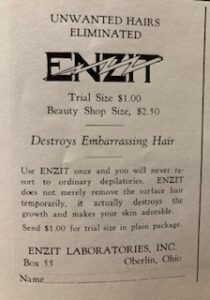

Figure 7. Advertisement for “Enzit” (Hi-oh-hi 1928).

In 1947, Enzit Chemical Company once again appeared in the U.S. Patent Index, with Philip Ohly renewing a patent for a depilatory. [However, it is a different patent number than he had in 1926] [16].

Conclusion

When I first started this research, I was hoping to show that “Enzit” was just a rebranded revision of “Flash.” However, I was unable to find a definite connection between the two companies (Oberlin Chemical Company and Enzit Laboratories), nor was I able to find a connection between Professor Jewett’s “Flash” and Philip Ohly’s “Enzit.” But, while I found no connection proving they are the same thing, I can show that they made use of similar advertising trends, symbols, and had a similar timeline.

First, both products are advertised towards women and removing unwanted hair, particularly from the face. Also, both products claim to remove not only the hair but the roots as well. In advertisements for “Flash” lightning bolts appeared around the word, while “Enzit” had a lightning bolt through their trademarked name. Finally, the first record of “Flash” dates to 1921, while a Pharmaceutical Era article in 1926, said that Philip Ohly had been working on the formula for “Enzit” for eight years, meaning he started his work in 1918, three years before “Flash” was advertised [17].

So, while these two depilatory brands (may or) may not be the same formula, their advertisements and goals mirror each other and show a trend in hair removal in 1920s Oberlin. Through research, I was never able to determine the chemical properties of these two depilatories, nor determine how they supposedly worked.

Today, many different hair removal methods and depilatories appear on the market. Popular hair depilatories, such as “Nair,” still target women in their advertisements, talking about ‘smoothness’ and featuring women in bathing suits [18].

This post is a local glimpse into a national trend and a possible entry point for study of the beauty industry, chemistry, patent law, and the interplay of advertising and gender expectations.

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to the Cleveland Public Library Staff and Oberlin College Archives for providing many of the resources used in my research and for all their help and advice.

Sources Consulted [Footnotes]

Alexandra A Fernandez BA, Katlein França MD, MSc, Anna H Chacon MD, Keyvan Nouri MD, From flint razors to lasers: a timeline of hair removal methods, (Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology), 2013 [3]

Annual report of the Secretary of State to the Governor of Ohio, June 30, 1922 [9]

“Beauty Parlor Opens Thursday” (Oberlin Review), May 10, 1921 [7]

“Clean Limbed Loveliness free from Hair” (Cleveland Plain Dealer), June 5, 1927 [15]

Department Reports of the State of Ohio, October 16, 1921 – April 6, 1922

“Enzit” (Hi-oh-hi), 1928

“Flash” (Oberlin College Alumni Magazine), July 1921 [8]

“Flash” (Oberlin College Alumni Magazine), May 1922 [11]

“General Nair Questions” (Nair.com). Accessed July 23, 2022. [18]

Kirsten Hansen, Hair or Bare?: The History of American Women and Hair Removal, 1914-1934 (Barnard College), 2017 [1, 5]

“New Company at Work” (Oberlin News), April 20, 1921 [6]

“A New Hair Remover that Does Amazing Things” (Oberlin College Alumni Magazine), November 1926

Pharmaceutical Era, 1926 [17]

“Phil Ohly Becomes Manufacturer” (Oberlin College Alumni Magazine), November 1926 [16]

“Secure Sales Rights for Flash in America” (Oberlin News), November 2, 1921 [10]

Smithsonian, Hair Removal (Cosmetics and Personal Care Products in the Medicine and Science Collections), No Date [4]

Taylor Barringer, History of Hair Removal – Products and methods for hair removal from the ages. (Elle Fashion), 2013 [2]

“Tomorrow Campus View Beauty Parlor Opens” (Oberlin News), May 11, 1921

United States Patent Index for 1926 [12]

https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/indexofpatentsis1926unit

United State Patent Index for 1947 [14]

“Unwanted Hairs Enzit” (Oberlin College Alumni Magazine), January 1927 [14]