History of the Morgan Street Water Works

By OHC Executive Director Liz Schultz

The complex of structures on Morgan Street known as the Water Works tells the history of Oberlin’s growth as a city, continuous efforts to problem-solve through science and engineering, and leadership in civic improvements. Part of that legacy resulted in Oberlin installing the first municipal lime and soda water softening plant in the nation.

Early Water History of Oberlin

Prior to the construction of the Morgan Street Water Works most home owners and businesses obtained water through private and shared wells, cisterns, or even Plum Creek. While perhaps adequate, such sources were susceptible to contamination and could more easily spread waterborne diseases such as typhoid and dysentery. They also limited the town’s ability to fight fires, including the disastrous fire that burned through downtown in 1882. Despite strong advocacy by Judge John Steele, some residents continued to prefer the “bucket brigade” to a high-pressure hydrant system. Just as the city was contemplating borrowing money to build a city water system in spring of 1886, another fire blazed across the southwest block of downtown.

Voters passed a $50,000 bond in April 1886 and after testing various sources it was agreed that the Vermilion River supply be adopted. Oberlin College also contributed over $5,000 toward the costs. Permission was obtained from Kipton property owners to lay line to transport the water, much of which was installed by Italian immigrants from Pittsburgh. The city also built a reservoir and pump station and purchased boilers and pumps. Local leaders in these efforts included Judge Steele, Edwin Regal, Professor Albert A. Wright, Professor Frank F. Jewett and Engineers H. F. Dunham and W. B. Gerrish. By September of 1887 there was enough water in the system to impress townspeople with a demonstration of shooting water from a hydrant up and over the 110 foot flag pole in front of the Union School on South Main Street. Service was inaugurated on December 23, 1887 and by spring of 1888 construction was complete.

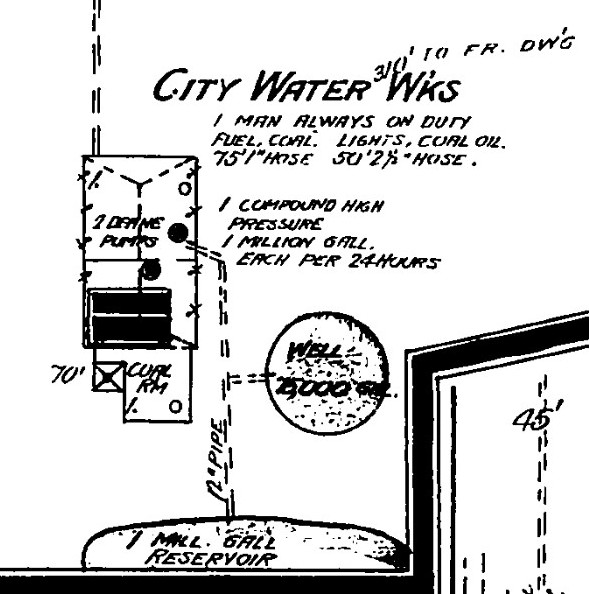

1888 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map showing the early layout of the water works near the corner of Morgan and Cedar Streets, including a pump station on the left, circular well, and 1 million gallon reservoir to the south.

In August 1893 a 66,000 gallon steel tank was set on a 40 foot stone tower – the tower many residents recognize today. Water shortages in the 1890s prompted the construction of an additional 15,000,000 gallon reservoir. Early engineers or superintendents at the water works included Henry Braithwaite, Doren E. Lyon, and H. V. Zahm.

By 1900 Oberlin was pumping 36,560,000 gallons of water a year. (According to a report from the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, in 2002 Oberlin averaged 640,000 gallons a day). Water was provided free in horse troughs and sprinkler systems that kept the road dust at bay. Businesses and industries generally connected earlier with the new water supply while home owners gradually tapped in, by their own choice. Additional water mains were added by street and block over the years. Some less affluent areas, which were also often predominately black residential areas, struggled far longer without access to the city supply.

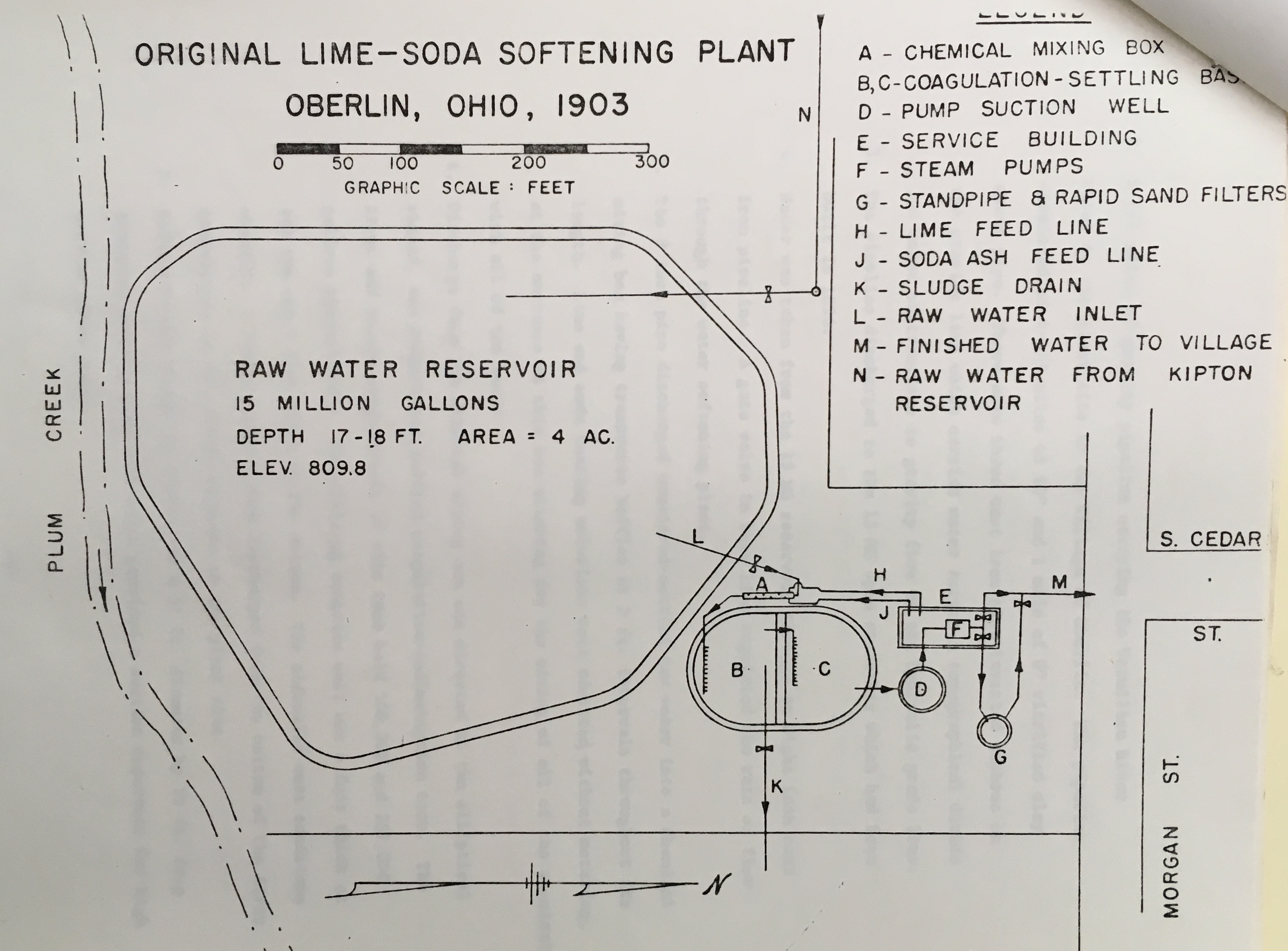

Diagram of the 1903 water works from the paper “America’s First Municipal Lime-Soda Softening Plant is Replaced”

by Raymond Fuller and Kenneth Cosens

Nation’s First Municipal Water Softening Plant

The water that supplied Oberlin’s public water system was hard, containing dissolved calcium and magnesium. In 1927 W. H. Chapin reported that the hardness of Oberlin’s natural supply, measured in calcium carbonate, averaged 270 parts per million. According to the USGS, this number today is classified as “very hard.” While that level was safe to drink, it was not to everyone’s taste. It was also not ideal for washing or bathing because soap does not lather well in hard water. Even after connecting to the public water supply some Oberlin residents continued to use rainwater from their cistern for washing.

Not content with the water quality, the village of Oberlin set about investigating the possibility of softening their supply and in 1903 it installed the first municipal lime-soda water softening plant in America.

C. Arthur Brown, a chemist and bacteriologist from Lorain who was consulted on the project, related the following.

All in all, the water was one that would have satisfied most cities. But Oberlin is different… The public-spirited and progressive city fathers decided that the best they could get was none too good for the city. While the water was satisfactory in most respects, it was a hard water and many of the citizens refused to use it for bath, laundry and cooking purposes, and it was feared at some time or other possible contamination of the water might occur and Oberlin have the same experience as Cornell University did with a typhoid epidemic.

In addition to Brown and city officials, Professors Wright and Jewett, William B. Gerrish, and W. B. Bedortha were involved in this next stage of development.

The softening process itself involved dissolving soda ash and lime with water in the pumping station, adding that mixture to the water coming in from the reservoirs, letting the water mix through a series of baffles in settling basins, allowing adequate time for the chemical reactions to occur (nearly a week), treating the water for purity, pumping it up to the water tower/standpipe, and then dropping it through sand filters and into the city’s mains. While successful, the process needed to be monitored for the greater processing time required during cold weather, the high amounts of silt that resulted, and the side effect of precipitates making it into the mains and clogging them.

Word began to spread about Oberlin’s new plant. City Engineer William Gerrish published the paper “The Municipal Water-Softening Plant at Oberlin, Ohio” in the Journal of the New England Water Works Association and responded in print to questions about the process. C. Arthur Brown presented a paper to a club of professional men in Joliet, Illinois, which was also reprinted in the Oberlin News. According to the Oberlin News, Gerrish even received a request from Moscow, Russia for information on the water-softening process.

Rise and Fall of the Morgan Street Water Works

Over the years the city implemented many improvements at the Morgan Street Water Works, including replacing the original sand filters with excelsior filters, adding more water sources after significant droughts, increasing the settling period to reduce incrustations in the water mains by adding a 10,000,000 reservoir in 1916, chlorinating the water, adding a recarbonation process, and even replacing the entire conduit line to Kipton in the 1930s.

But some issues persisted, including the continual build-up of sediments from the process, aging equipment, and increasing demands for water. By the time of the 1916 Annual Report of the Village of Oberlin there were concerns about the increased cost of soda ash and the new “Eight Hour Law” limiting the work day of engineers at the plant. The largest costs listed in the report included coal, salaries, chemicals, and construction. Coal consumed for the year: 684,000 lbs. Total pumpage for the year: 104,373,000 gallons.

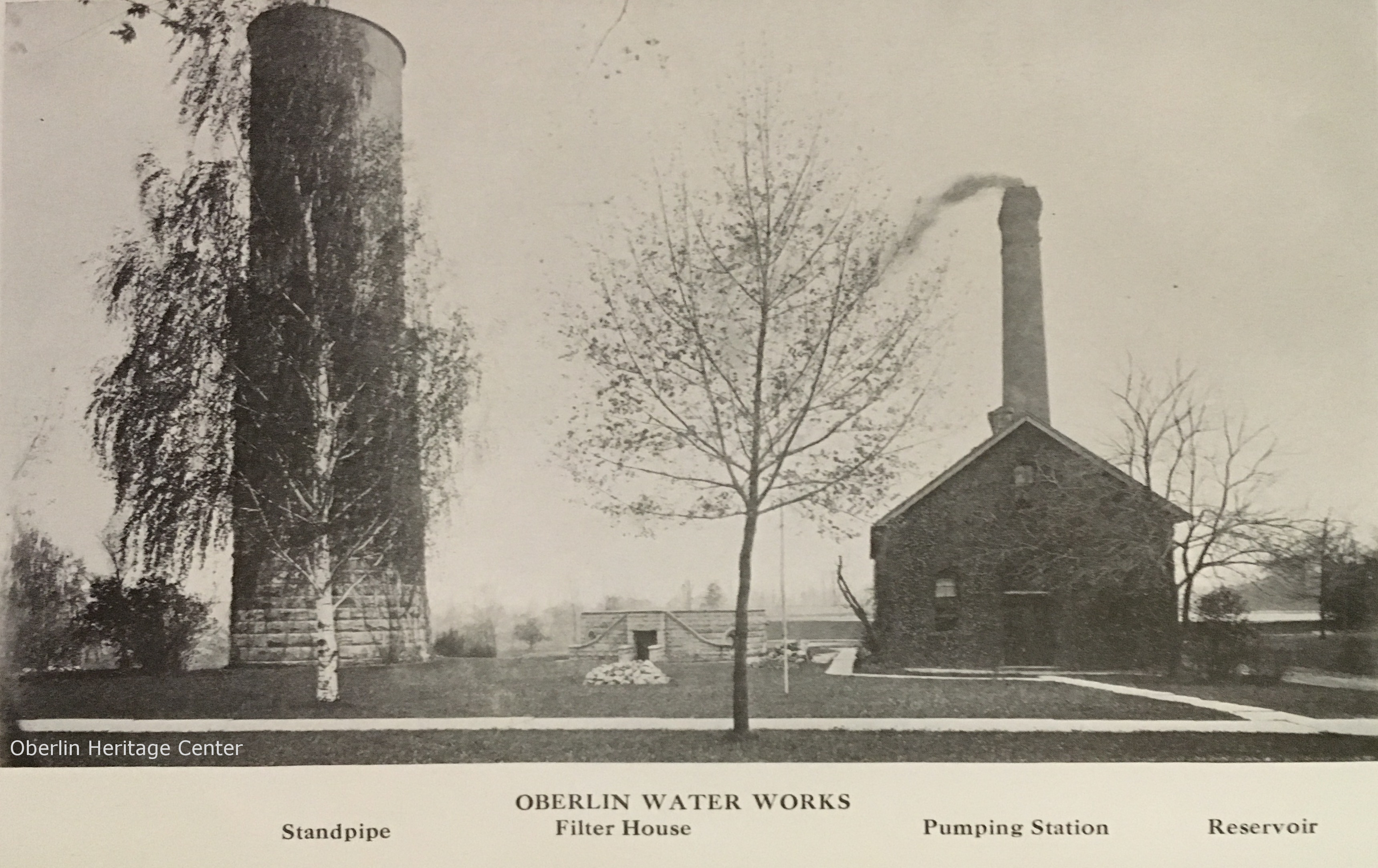

Photograph from the 1916 Annual Report of the Village of Oberlin

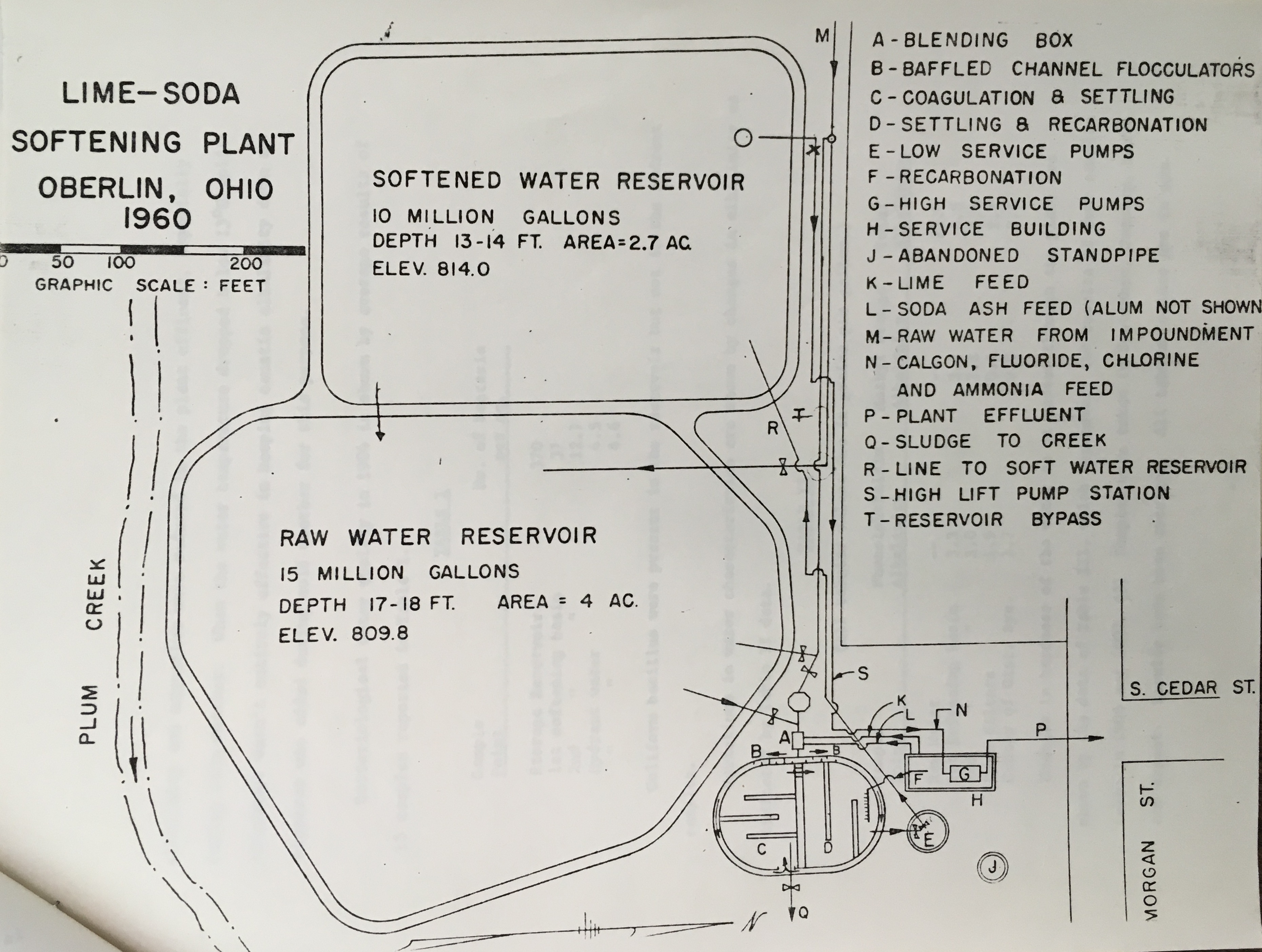

Diagram of the 1960 water works, just before production moved to the Parson Road facility, from the paper “America’s First Municipal Lime-Soda Softening Plant is Replaced”

Nation-wide water shortages around the 1950s and dwindling water flow from the Kipton Reservoir prompted the construction of the newer reservoir and pumping system on Parsons Road in 1960, sourced from the Black River.

Recreation

Photographs indicate that the water works and reservoirs were enjoyed recreationally from the very beginning. While fishing and (prohibited) swimming, may be popular now, residents likely enjoyed the reservoirs with their eyes alone while they were the city water supply.

Copy of a photograph showing Carol Kohut as a toddler at the reservoir.

John Elder recalled rolling down the rare hills as a young boy and then as a college student borrowing trays from the dining hall to go sledding. He also recalled ice skating there, as did others, until they were shooed off.

In an oral history interview Charles Peterson recalled the Fourth of July in 2001, when fireworks were still launched behind the City Manager’s House near the water works.

The bowl by the reservoir was just packed with people and there were vendors and food, and there was music and everybody was smiling and the children were playing. And I just remember sort of standing on the street looking over the bowl thinking, “Oh my god, this is absolutely amazing!” That this town has so much spirit and the intimacy of it and everyone knew each other and were old friends and were open to new people coming. And I thought, this is, you know, I think that was the first time I really began to realize what a special place Oberlin is, and that’s a memory.

Legacy

Every year the Oberlin third graders are introduced to the history of the Morgan Street Water Works on their annual bus tour of Oberlin, but for many residents the stone tower, brick gabled pumping station, and grassy basin are mysterious remnants of an earlier time. The tower, without its original metal tank on top, is designated as a City of Oberlin Landmark, which means any proposed exterior alterations must be approved by the city’s Historic Preservation Commission. The older 1887 brick pump station was not included on the landmark designation renewal form of 2001. Years of disuse and neglect have taken their toll on the building and perhaps it is doubly sad that a fire in 2011 damaged the rear part of this building, which was constructed in very large part to combat that exact menace. Ideally this building will continue to be part of Oberlin’s natural and historic landscape and continue to tell this locally- and nationally-significant history.

If you have more to add to this story, please contact [email protected].

Sources

Annual Report of The Village of Oberlin, Fiscal Year 1916. Oberlin: Press of the News, 1917 [Copy held in the collections of the Oberlin Heritage Center]

Blodgett, Geoffrey. Oberlin Architecture, College and Town. Oberlin: Oberlin College, 1990.

Chapin, W. H. “Water-Softening as Practiced at Oberlin, Ohio.” Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 19 (1927): 1182-1187.

Cosens, Kenneth W. and Raymond Fuller. “America’s First Municipal Lime-Soda Softening Plant is Replaced.” No date. [Copy held in the collections of the Oberlin Heritage Center.]

Gerrish, William. “The Municipal Water-Softening Plan at Oberlin, Ohio.” Journal of the New England Water Works Association 19 (1905): 422-436.

Jones, George T., “The History of Utilities in Oberlin,” in Oberlin Community History, edited by Allan Patterson, 52-58. State College, PA: Josten’s Publications, 1981.

Oberlin News. “Paper on Oberlin’s Water Works System.” January 2, 1906.

Oberlin News-Tribune. “Water Plant Monument to John Steele.” March 29, 1935.

Oberlin Weekly News. “Information About the Water Works.” September 8, 1887.

Oberlin Weekly News. “A Partial Exhibition…” September 8, 1887.

Oral History Interview with John Elder by Rachel Hood and Haley Johnson, 5 April 2017. Oberlin Oral History Project and Environmental Studies 101 Community Engagement Project, held by the Oberlin Heritage Center, Oberlin, Ohio.

Oral History Interview with Frank Zavodsky by Rob McLean, 19 January 1987. Oberlin Oral History Project, held by the Oberlin Heritage Center, Oberlin, Ohio.

Oral History Interview with Charles Peterson by Jeanne McKibben, 13 June 2009. Oberlin Oral History Project, held by the Oberlin Heritage Center, Oberlin, Ohio.

Paynter, Braden. “Mud, Fire, and Telephones: Oberlin College and the Modernization of Oberlin 1870-1907.” Honors Thesis, Oberlin College History Department, 2005.

Phillips, Wilbur. Oberlin Colony: The Story of a Century. Oberlin: Press of the Oberlin Printing Company, 1933.

Report of the Oberlin Water Works Board. No date.

Photographic Image Sources,

William Annable

Kathy DeRuyter

Tags: Hard Water, morgan street, Municipal Water, Oberlin, Oberlin Firsts, Public Water, Reservoir, Water Softening, Water Works