Integrating Oberlin’s Barber Shops, 1944-45

Thursday, February 25th, 2016By Mary Manning, Ph.D., 2015-16 Local History Corps AmeriCorps Member

Examining the history of Oberlin’s barber shops means addressing a situation in which overt discrimination was standard practice, far into the twentieth century and throughout the United States. In 1940, Oberlin had 4,305 citizens, and 897 of them were black. [1] Yet, by this time, there were no barbers in town who would serve African-American customers in their shops during regular business hours. This post presents the story of how, at the height of World War II, discrimination in the barber shops became a town-wide topic of discussion and, subsequently, a cause for social action.

In the early 1940s, when an African-American man in Oberlin wanted a haircut, he would need to go to a barber, like Walker Fair, who cut hair at his home during off hours. Though these black barbers loyally served the African-American community, barbering was only a side gig. Most of them also worked full-time jobs, either as laborers in town or in industrial jobs in nearby cities like Elyria. Many white Oberlinians did not realize this racial divide existed until, at a night meeting at Oberlin College’s Graduate School of Theology, an African-American student announced that he was leaving to go get a haircut. At first, the white students did not understand—where could someone get a haircut at that time of night? Once it became clear that the barber shops patronized by white students and faculty were off limits to black students, these men decided to act. [2]

Headline in The Oberlin News-Tribune, May 11, 1944. (Image from Oberlin College Special Collections.)

On May 4, 1944, some of these students staged protests in local barber shops. Two groups with both black and white members, one led by Reverend Joseph F. King, then the pastor at First Church, and the other led by Larry Durgin, a theological school student, went into two of the shops in town and stated that they would like shaves or haircuts. The white members of each group also stated that they would gladly wait to be served until after the barbers had attended to the black members of their group. The barbers, in turn, claimed that “they did not have the ‘necessary experience, that technical difficulties were involved which would make successful work on Negro hair impossible.’” [3] As the protesters explained their presence to every new customer that entered, and some of those customers simply chose to leave, the confronted barbers closed their doors on that day rather than give in to the protesters.

With this non-violent action, integration in the barber shops provoked heated dialogue in town. Because the effect of the protest was so great, the Oberlin News-Tribune immediately took a stand in its editorial published on May 11. Though the editor, Charles Mosher, criticized the tactics of the students and their allies, illuminating aspects of the increasing town and gown divide, he declared: “like a dash of cold water in our faces, [the protests] awoke many of us to realization that race segregation in the barber shops is no credit to Oberlin.” [4] Mosher would later say, in an oral history interview, that “no event in Oberlin…since the Wellington rescue came so close to inflamed violence.” [5] It was also Mosher, in that editorial, who proposed a solution: “buy one of the local barber shops and operate it on a bi-racial policy.” [6]

On the Sunday after the newspaper published Mosher’s editorial, Dr. Walter Horton, a theology professor substituting for Reverend King at First Church, also forcefully addressed the topic in his sermon. He invoked the intentions of Oberlin’s founders to create “an ideal community,” and he reminded the congregation of the city’s historic commitment to “the equality of all men before God.” On the subject of the barber shops, Horton cut straight to the heart of the matter, saying: ‘The right to have a hair-cut at convenient hours, without going out of town or suffering humiliating rebuffs from the only shops open, may not be as important as the rights to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’; but the denial of this elementary human service in Oberlin constitutes a reversal of all our most sacred traditions and casts a cloud over the reputation for fair play for which we are famous.” [7]

Thus, the theological students and professors, with the support and counsel of prominent Oberlinians, including the activist Robert Thomas and Mount Zion Baptist Church’s Reverend Normal C. Crosby, determined to follow Mosher’s recommendation. They would call themselves the Barber Shop Harmony Committee, and they would raise funds to buy out a local shop and hire a barber from out of town who would commit to running an integrated shop. By the end of their first meeting on June 19, thirty-seven members of the community had pledged $541 toward the fund. [8] By September, the committee had calculated that they would need at least $2,500 to execute their plan, and they decided to sell stock at $1 per share, an affordable price even for student supporters. [9] They would eventually purchase a shop from Bill Winder, one of the barbers targeted in the May 4 protests. On October 31, the Barber Shop Harmony Committee finalized a deal with Winder to buy his shop at 42 ½ South Main St. for $1,250. They then acknowledged their vision of social progress through their decision to rechristen Winder’s space as the Cosmopolitan Barber Shop. [10]

Despite the clear successes of their fundraising and the shop’s purchase, the Cosmopolitan Barber Shop still lacked one item without which it could not operate: the willing barber. At first, they hired a man from Washington, D.C., who would arrive at the end of October but who then “had his plans changed by personal affairs.” [11] Though they had intended to open on November 1, they could not open for another ten days, by which time they had secured the services of a barber whose name was Jerry Mizuiri. Mizuiri (“pronounced like Missouri,” noted the newspaper) was a Japanese-American from Oakland, California. [12]

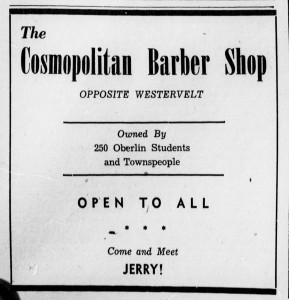

Advertisement in The Oberlin Review, Nov. 11, 1944. (Image from the Oberlin College Archives.)

However, in 1944, World War II raged abroad. The Oberlin News-Tribune, on December 28 of that year, would list the names of over 700 local people in service overseas, along with 16 names of local men who had died, 3 who remained prisoners of war, and the approximately 50 men who had already been honorably discharged, perhaps due to injuries. [13] Many of these servicemen fought in the especially brutal Pacific theater of the war while, in the United States, the perceived threat of Japanese invasion had resulted in over 100,000 Japanese-Americans being removed from their West Coast homes and interned in camps further inland by a federal agency, the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Though Mizuiri was an American citizen by birth, he had been relocated to an internment camp in Northern California. [14] He was then sent to Cleveland, where a satellite office of the WRA funneled displaced Japanese-American workers into local industrial and clerical jobs. [15] Employers, such as Oberlin’s Cosmopolitan Barber Shop, might send job notices to the WRA office, who would then place qualified workers in those roles. Mizuiri’s arrival in Oberlin for the purpose of running an integrated shop was so noteworthy that Time Magazine even briefly covered it. In a very short item titled “Tonsorial Tolerance,” the magazine let its readers infer the irony of the situation by noting that white students could finally get their hair cut “beside Negroes” by a barber who was a “Nisei,” a Japanese term meaning “second generation.” [16]

Though wartime Oberlin now had the potential to transcend the black/white racial barrier, business at the Cosmopolitan Barber Shop did not immediately boom. Mizuiri was far from the only Japanese-American person to be relocated and employed in the area, but the fact remained that anti-Japanese rhetoric remained a significant component of the era’s homefront propaganda. Town activist and barber shop corporation member Robert Thomas recalled later, in 1979, that a number of town residents had expressed to him that they preferred not to have Mizuiri “fooling around their heads with a razor.” [17] Consequently, this other means of racial discrimination made it difficult for the integrated barber shop to meet its social goals. The directors of the shop’s corporation tracked the racial identities of people who patronized the shop over its first few months of existence and estimated that only five percent of their customers were actually African-American. [18]

Soon, outside circumstances again took over from the men who ran the Cosmopolitan Barber Shop—the West Coast reopened to Japanese-Americans, and it was becoming increasingly clear that the Allied Powers would triumph in the war. By May 1945, Mizuiri left Oberlin, eventually to rejoin his family in California.[19] In seeking another barber, the committee found Robert Taliaferro, a man perhaps more suited to pleasing the Oberlin community. Besides working as a barber in Wooster, Wellington, and Cleveland, Taliaferro was an African-American Baptist minister. With the untimely presence of a Japanese-American barber removed from the equation, business steadily picked up.

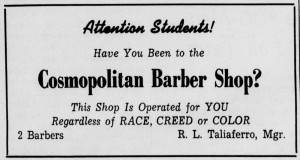

Advertisement in The Oberlin Review, July 12, 1946. (Image from the Oberlin College Archives.)

With Taliaferro at the helm, the Cosmopolitan Barber Shop could finally be viewed as a success, so much so that, by 1946, they decided to hire a second barber. By chance, Gerald Scott happened to be looking for a new place to settle down. While walking through downtown Oberlin, already enamored with the beauty of the area, he saw a “Barber Wanted” sign in a window and immediately applied. An African-American man who had been working as a barber in Wooster, Scott would take over the shop’s second chair and eventually become known to everyone in town as Scotty. After four years, with the Cosmopolitan Barber Shop deemed both a social and a financial success, the corporation decided to sell the business. When Taliaferro, by then an older man, passed on their offer, Scotty bought the shop, agreeing to the condition that it would always remain integrated. [20]

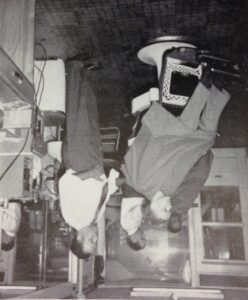

Scott Brothers Barber Shop ca. 1948 (Image from 1948 Hi-O-Hi Oberlin High School Yearbook.)

Though Oberlin’s racial struggles certainly did not end with the founding of the Barber Shop Harmony Committee, Scotty would spend the rest of his life as a barber in Oberlin and become one of the town’s most beloved businessmen. More importantly, integrated barber shops became the norm, and African-American barbers from then on had the option of serving both black and white customers in their own storefront shops. Scotty was eventually joined in town by George Goodson and Ray Murphy, who both grew up in Oberlin, served in World War II, and then came home to make their careers as barbers in integrated Oberlin shops. Though twentieth-century Oberlin faced the same racial struggles as the rest of the United States, men like these barbers provided welcoming spaces that could unite members of the community, even if only for the time it took to get a haircut.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

“Barber Shop Harmony,” The Oberlin News-Tribune, May 11, 1944, p.4.

Charles Adams and Harriet Johnson Mosher. Interview by Marlene Merrill. Oberlin Oral History Project, Series I. Oberlin Heritage Center, Oberlin, OH. May 9-10, 1983.

“Committee to Purchase Winder Shop,” The Oberlin News-Tribune, Sept. 21, 1944, p. 1.

“Cosmopolitan Barber Shop Subscribers to Meet Next Thursday,” The Oberlin News-Tribune, May 3, 1945, p. 1.

George Jones, Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Thomas, and Robert ‘Bob’ Thomas. Interview by Allan Patterson. Oberlin Oral History Project, Series I. Oberlin Heritage Center, Oberlin, OH. Nov. 17, 1984.

Gerald Scott. Interview by Mildred Chapin. Oberlin Oral History Project, Series I. Oberlin Heritage Center, Oberlin, OH. Nov. 14, 1986.

“Horton Discusses Segregation Controversy in the Light of Oberlin’s Historic Ideals,” Oberlin News-Tribune, May 18, 1944, p. 4.

“Inter-Racial Barber Shop Completes Deal with Winder,” The Oberlin News-Tribune, Nov. 2, 1944, p. 1.

“Japanese.” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

“Jerry Mizuiri.” San Francisco Chronicle, Apr. 22, 2009.

“Mizuire, Ichiro J.” File Unit: Japanese-American Internee Data File, 1942 – 1946. Series: Records about Japanese-Americans Relocated During World War II, created 1988-89, documenting the period 1942-46; Record Group 210. National Archives and Records Administration.

“Oberlin Does Not Forget!” The Oberlin News-Tribune, Dec. 28, 1944, p. 1

Robert ‘Bob’ Thomas. Interview by Peter Way. Oberlin Oral History Project, Series I. Oberlin Heritage Center, Oberlin, OH. April 19, 1979.

Roland M. Baumann, Constructing Black Education at Oberlin College

“Theology Groups Test Race Views of Barber Shops,” The Oberlin Review, vol. 72A, no. 24, May 12, 1944, p. 1.

“Tonsorial Tolerance,” Time Magazine, Nov. 27, 1944, p. 44.

“To Raise Fund for Bi-Racial Barber Shop,” The Oberlin News-Tribune, June 22, 1944, p. 1.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Baumann, p. 97

[2] Robert ‘Bob’ Thomas, interview, April 19, 1979.

[3] “Theology Groups Test Race Views of Barber Shops”

[4] “Barber Shop Harmony”

[5] Charles Adams and Harriet Johnson Mosher, interview, May 9-10, 1983.

[6] “Barber Shop Harmony”

[7] “Horton Discusses Segregation Controversy”

[8] “To Raise Fund for Bi-Racial Barber Shop”

[9] “Committee to Purchase Winder Shop”

[10] “Inter-Racial Barber Shop Completes Deal with Winder”

[11] “Committee to Purchase Winder Shop”; “Inter-Racial Barber Shop Completes Deal with Winder”

[12] “Inter-Racial Barber Shop is Now a Going Concern”

[13] “Oberlin Does Not Forget!”

[14] “Mizuire, Ichiro J.”

[15] “Japanese”

[16] “Tonsorial Tolerance”

[17] Robert ‘Bob’ Thomas, interview, April 19, 1979.

[18] George Jones, Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Thomas, and Robert ‘Bob’ Thomas, interview, Nov. 17, 1984.

[19] “Cosmopolitan Barber Shop Subscribers to Meet Next Thursday”; “Jerry Mizuiri”; Robert ‘Bob’ Thomas, interview, April 19, 1979.

[20] Gerald Scott, interview, Nov. 14, 1986.