August First – the original “Juneteenth”

Thursday, July 23rd, 2015by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent, researcher, and trustee

July 23, 2015

In my last blog, I wrote about how Juneteenth became a national celebration of the end of slavery in the United States. But before there was a Juneteenth, there was the First of August, to celebrate the end of slavery in the British West Indies. While it may not sound like a big deal to us today, West Indian Emancipation Day, as it was called, was a big deal in early Oberlin and other abolitionist and African American communities. In an era when American slaveholders were tightening the chains ever tighter on their bondsmen, West Indian Emancipation (which would soon lead to the extinction of legalized slavery throughout the British Empire) was a glimmer of hope just 600 miles from the American mainland.

West Indian Emancipation was the result of the labors of Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, and other British abolitionists who had devoted decades of their lives to the anti-slavery cause. A short but bloody slave uprising on the West Indian island of Jamaica during Christmas 1831 gave traction to the movement, and finally Parliament decreed that slavery in the British West Indies would be abolished beginning August 1, 1834. Three of the West Indian islands – Antigua, Montserrat, and Bermuda – would set their slaves free unconditionally on that date, while the other islands would begin a gradual emancipation plan, called “apprenticeship”, that would take several years. [1]

But whereas a bloody slave rebellion had helped lead to the emancipation of slaves in the British Empire, a similar rebellion in the United States at about the same time had exactly the opposite effect. Nat Turner’s rebellion in Virginia in August, 1831 caused slaveholders to tighten the chains (figuratively speaking) on their slaves all the more. Discouraged by the turn of events at home, American abolitionists and blacks looked to Britain as a sign of hope.

And so it was that the first August 1st celebration in the United States took place in New York City on August 1, 1834, and abolitionist missionaries, teachers, and reporters flocked to the British West Indies to observe and assist in the emancipation process. Among the early Americans to arrive there was Oberlin’s own Lane Rebel and future college professor, James Thome, who was commissioned by the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1837 to report on the progress of West Indian Emancipation. Not surprisingly, Thome reported that Antigua, which had experienced immediate, unconditional emancipation, “is the morning star of our nation, and though it glimmers faintly through a lurid sky, yet we hail it, and catch at every ray as the token of a bright sun which may yet burst gloriously upon us.” He was less sanguine about the gradual emancipation in the other islands, yet he still insisted “that we are much better off now than we have been for a long time.” Reports like these caused Arthur Tappan’s anti-slavery newspaper, The Emancipator, upon the completion of the British emancipation process in 1838, to declare that August 1st should be celebrated as a recurring holiday by abolitionists everywhere. [2]

So it was written, and so it was done, with annual celebrations spreading outward from New York and New England over the next several years. Oberlin’s first August First celebration occurred in 1842 under the leadership of Sabram Cox, an escaped slave who came to Oberlin to obtain an education a few years earlier and would remain the rest of his life as a key community leader. Assisting Cox was George B. Vashon, a free-born black who two years later would become the first African American to earn a Bachelor’s Degree at Oberlin College and then go on to become a teacher in Haiti (another Carribbean island that achieved emancipation, but in this case by a massive slave uprising in the 1790s). Also assisting was William P. Newman, another escaped slave and Oberlin College student who would go on to become an educator and minister to the fugitive slave colonies in Canada. The Oberlin Evangelist described the results of their efforts as follows:

Perhaps there has never been more interest felt, on any public occasion in this place, than at the celebration by the colored people, on the first [of this month]. The anniversary of the emancipation of 800,000 persons held in slavery in the British West Indies, must be a more interesting time to the friends of human rights, than the anniversary of American Independence, so long as the principles of the declaration of that independence are so utterly disregarded by our slave-holding and pro-slavery citizens. And then this was probably the first effort made by any portion of the colored people of Ohio to show their improvement and the effect of giving them equal rights. The idea of the celebration originated with, and all the arrangements were made and executed by the colored people, with scarcely a suggestion from others. And, no doubt, we speak the feelings of the very large audience in attendance, when we say that the whole was conceived and executed with excellent judgment, and good taste. We heard no expression but that of satisfaction and gratification.

The celebration lasted from morning to evening, with speeches by the organizers as well as Oberlin College President Asa Mahan, Professor John Morgan, and Professor Thome, who told of his personal experiences in the West Indies. As reported by the Evangelist, “The large chapel was crowded to excess, and the interest continued to the close, as was manifested by the earnest attention and moistened eye of many in the congregation… After the meeting, two hundred and fifty persons sat down to a plain free dinner, provided by the colored people, eighty of whom were at the table. Of these nearly one half had felt the galling chain of slavery.” [3]

The following year would see the celebration return, and the Oberlin Evangelist would once again report that “Throughout the whole, the true principle of equality, the essential brotherhood of man, prevailed, and the effect was most happy on all concerned.” In 1844, a new leader of the Oberlin African American community and the First of August celebrations would emerge in the person of Oberlin College student William Howard Day. Although only 18 years old at the time, Day would deliver a stirring address and become the chief organizer of the annual event for the next two years. Invoking the legacy of the African liberator Cinque, whose 1839 mutiny aboard the slave ship Amistad ultimately led to the liberty of its enslaved passengers, Day proclaimed: [4]

I love my country, but never can I sacrifice the rights of man for a love of country. The truth must be told: our country is guilty – we are guilty, and slavery must be abolished soon, or we may prepare to suffer the consequences. We have long enough clung to the faint hope of a change; we have long enough listened to the frequest whisper, “Peace, be still”, and now the call is for action. From the memorable rock of Plymouth, a beacon has been lighted by the fires of liberty. The irrevocable decree has gone forth from the Supreme Court of the universe – “Proclaim liberty to all the inhabitants thereof.” If such were the sentiments of the pilgrim fathers, if such be the command of God, liberty we can, and liberty we must have. If “coming events cast their shadows before”, who can prophesy that the decks of the Amistad and Creole are not the faint sketches of our future history. If a Cinque or a Washington shall hereafter rise, (which may God forbid) – if our land shall be deluged in blood – if your attention shall be directed to the Southern quarter by the roar of the booming cannon, and the shrieks of the wounded and dying – if devastation and ruin take the place of supposed peace – or if with the burning of villages they shall be enveloped in one common grave – you will be responsible. You have it in your power to avert it. The same means used for the abolition of Slavery in the West Indies, will avail now. Their efforts were few and feeble, but at last they conquered; and with the same well-directed efforts, with the same spirit, and with the dependence on the same God, we shall conquer.

Day would go on to have a long career of anti-slavery and equal rights advocacy, locally, nationally and internationally. (See my William Howard Day blog.) Among those listening to Day’s speech that August 1st was a frequent visitor to Oberlin, Mrs. Almira Porter Barnes, from Troy, New York. Mrs. Barnes was an abolitionist and moral reform activist who was on close terms with the Oberlin College establishment. She described the day’s events as follows:

… at eight oclock in the morning there was a prayer meeting [and] a number of prayers and addresses were made by both coulored [sic] and white[;] a white gentleman from Jamaca [sic] was present who was a slaveholder untill [sic] a short time previous to Emancipation and gave us some account of the manner in which the day was kept there and the effect it had had upon the slaveholder and the slave. At three o’clock in the after noon a large assembly met in the church and listened to several addresses from coulored young men that would have done honor to students from any institution in the country. A dinner was provided by the coulored people and between two and three hundred invitations given including of course the professors families and distinguished strangers like myself. After partaking of an excellent repast consisting of pyes [sic] cake fruit &c we had some excellent singing and some appropriate remarks by a Mr Hall a Baptist Minister who formerly preached in Rochester and then the invited company dispersed and the tables were filled again with any who were disposed to partake… [5]

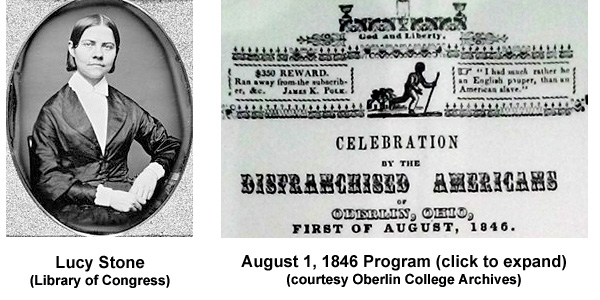

The African American organizers of the Oberlin August First celebrations also welcomed participation by women. Many of the female participants prepared essays that were read to the audience by male proxies, in deference to the contemporary tabboo against women orators sharing the stage with men and speaking before a mixed audience. In 1846, Oberlin resident Mary Hester Crabb, an emancipated slave, and Oberlin College student Emeline Crooker had their essays read, and the following year, Oberlin College student Antoinette Brown (who would become the first female ordained minister in the United States in 1853) also wrote an essay. But the event organizers were also amenable to women who would dare to defy the public speaking tabboo. On August 1, 1846, Oberlin College student Lucy Stone did just that, and in the words of one reporter, “in a clear, full tone, read her own article”. The speech, entitled “Why Do We Rejoice Today?”, was the first in an illustrious speaking career that spanned several decades. (See my Lucy Stone blog). The following is an excerpt: [6]

We rejoice to-day, not simply because the genius of freedom is now presiding and scattering blessings, where eight years ago the Demon of slavery brooded; – nor merely that where ignorance and heathenism then prevailed, the light of science and christianity is now dawning; – nor yet because to-day is the anniversary of the moral and political birth-day of eight hundred thousand human beings, – but we rejoice in the grander fact, that in one of the largest and most influential kingdoms of the world, a public sentiment exists which shivers the chains of the slave and lets “the oppressed go free” – which practically recognizes the equal brotherhood and inalienable rights of man…

The doom of slavery everywhere is sealed in the public sentiment which caused England to reach out her hand over the broad Atlantic, to lift up from his deep degradation, and make conscious of his manhood, the bondman pining there. The influence of that event will be wide as the world, and longer than the stream of time.

But as Oberlinites and abolitionists found hope and cheer in the example set by the British, the political leaders of the American slaveholding states had a vastly different view of the situation. To them West Indian emancipation was a catastrophe like none other, to be avoided at all costs. Just months before William Howard Day delivered his first August 1st address, and as Thomas Clarkson and other British abolitionists were turning their attention towards worldwide abolition, U.S. Secretary of State John C. Calhoun, one of the South’s most powerful slaveholders, wrote to the British Foreign Minister and warned him that if Britain were to “succeed in accomplishing in the United States, what she avows to be her desire and the object of her constant exertions to effect throughout the world, so far from being wise or humane, she would involve in the greatest calamity the whole country.” The following year, South Carolina Governor James Hammond went a step further in a scathing letter to Clarkson himself, declaring that the anti-slavery agitation of recent years had served only to drive American slaveholders into “a close examination of the subject in all its bearings, and the result had been an universal conviction that in holding Slaves we violate no law of God – inflict no injustice on any of his creatures – while the terrible consequences of emancipation to all parties and the world at large, clearly revealed to us, make us shudder at the bare thought of it.” Even fifteen years later, as Alabama prepared to secede from the Union on the eve of the Civil War, Alabama secession commissioner Stephen Hale warned the Governor of Kentucky that if secession failed, “the dark pall of barbarism must soon gather over our sunny land, and the scenes of West India emancipation, with its attendant horrors and crimes (that monument of British fanaticism and folly), be re-enacted in our own land upon a more gigantic scale.” [7]

Clearly the road to Juneteenth in the United States would be a vastly more difficult path than the road to August 1st had been in the British Empire. But with the British example before it, Oberlin would stay the course through many more August 1st commemorations. Even as late as August 1, 1862, in the midst of bloody civil war, at a meeting chaired by Oberlin College graduate Elias Toussaint Jones, its “citizens irrespective of color” would resolve:

That this day – the memorial day of Freedom to 800,000 slaves in the West Indies – was the first instalment [sic] in modern times of the redeeming power of true Christian civilization upon the destinies of the oppressed; that the work begun then and there still progresses and cannot cease till the same power shall have pervaded every Christian nation, not excepting our own; that we have unmistakeable indications that God is moving his almighty agencies towards this result; that the insane rebellion of the South was permitted and will be over-ruled of God to this end, and that a thousand lesser subordinate events conspire to assure us that the day of universal emancipation in this country is at hand. [8]

Eight weeks later President Lincoln would unveil to the nation his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

“First of August – Colored People”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 17, 1842, p. 5

“The First of August”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 16, 1843, p. 7

“The First of August”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 14, 1844, p. 7

“Emancipation in the West Indies. Slavery in America”, The Oberlin Evangelist, Nov 6, 1844, p. 3

“First of August”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 14, 1845, p. 6

“First of August in Oberlin”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 19, 1846, p. 6

“Jamaica”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 18,1847, p. 6

“First of August”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 18,1852, pp. 6-7

“Annual Report of the Female A. S. Soc”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 15,1855, p. 7

“First of August in Oberlin”, The Oberlin Evangelist, July 30, 1862, p. 7

“First of August in Oberlin (Concluded from our last)”, The Oberlin Evangelist, August 13, 1862, pp. 5-6

“Why do we rejoice to-day?”, Anti-Slavery Bugle, November 27, 1846, p. 3

Almira Porter Barnes to Mrs. Laura Willard, August 12, 1844, Oberlin College Archives, Robert S. Fletcher collection, RG30/24, Box 3, Folder: “Correspondence – Misc pre-1865”

Dr. John Oldfield, “British Anti-Slavery“, February 17, 2011, BBC

James A. Thome, Joseph Horace Kimball, Emancipation in the West Indies

Benjamin Quarles, Black Abolitionists

Todd Mealy, Aliened American: A Biography of William Howard Day, 1825-1865, Volume 1

“Celebration of the Disenfranchised Americans of Oberlin, Ohio, First of August, 1846”, Oberlin College Archives, Oberlin File, RG21, Series XI, Box 2

John C. Calhoun, letter to Mr. Pakenham, April 18, 1844, Proceedings of the Senate and Documents Relative to Texas, from which the Injunction of Secrecy Has Been Removed, p. 53

James Henry Hammond to Thomas Clarkson, March 24, 1845, The Pro-Slavery Argument: as Maintained by the Most Distinguished Writers of the Southern States, pp. 169-170

Stephen F. Hale, letter to Gov. B. McGoffin of Kentucky, December 27, 1860, Official Records of the Rebellion, Series 4, Volume 1, p. 9

Gale L. Kenny, Contentious Liberties: American Abolitionists in Post-Emancipation Jamaica

John Stauffer, “American Responses to British Emancipation: The Problem of Progress“, Third Annual Gilder Lehrman Center International Conference at Yale University, October 25-28, 2001

Kevin O’Brien Chang, “Sam Sharpe – Emancipation Hero“, July 27, 2012, The Gleaner

Lucy Stone to “Dear Father and Mother”, August 16, 1846, Oberlin College Archives, Robert S. Fletcher collection, RG30/24, Box 10, Folder 2

Carol Lasser and Marlene Deahl Merrill, ed., Friends & Sisters: Letters Between Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell, 1846-93

Roland M. Baumann, “A Voice Beneath History: the Story of Mary Hester Crabb”, presentation at Oberlin Public Library, February 1, 2014

William Cheek and Aimee Lee Cheek, John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1829-65

Robert Samuel Fletcher, A History of Oberlin College From its Foundation through the Civil War, volume 1

General Catalogue of Oberlin College: 1833- 1908

“Minority Student Records“, Oberlin College Archives, RG 5/4/3

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Kenny, pp. 55-56

[2] Quarles, pp. 123, 124; Thome, pp. 209, 478

[3] Oberlin Evangelist, August 17, 1842

[4] Oberlin Evangelist, August 16, 1843; Mealy, pp. 123-124; “Celebration”; Oberlin Evangelist, Nov 6, 1844

[5] Barnes

[6] Baumann; “Celebration”; Lasser, p. 24; Stone to “Dear Father and Mother”; “Why do we rejoice to-day?”

[8] Oberlin Evangelist, July 30, 1862