The Battle of the Crater: 150 years ago

Friday, July 25th, 2014by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent

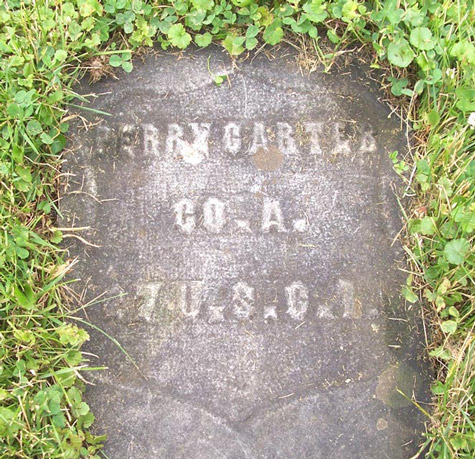

The party was such a success that it would make the local paper. Fifty guests crowded into the house on South Water Street (present day Park Street) – among them the Mayor of Oberlin, Civil War veterans, and a pastor of Rust Methodist Episcopal Church – and now they called for a speech. They would not be disappointed. Their host, Perry Carter, would captivate them for the next half hour with tales of his escape from slavery to Oberlin, his service in the Union Army, and his roles in the Republican Party and the Rust M. E. Church. And while most of these stories have been lost to history, we do have a good deal of information about one of the most fascinating episodes of Perry Carter’s life: the Battle of the Crater, one of the most dramatic and horrendous battles of the Civil War, fought 26 years before Carter’s party and 150 years ago this week. [1]

Perry Carter came “directly to Oberlin” in the late 1850s, in his early 20s, after having escaped from slavery in Kentucky. He was working as a drayman when many of Oberlin’s citizens went off to fight the Civil War in 1861. But the vast majority of those soldiers were white, as the racial attitudes of the day barred blacks from serving legally. That would change, however, and towards the end of 1863 Ohio began to recruit its own African American regiments: the 5th and 27th United States Colored Troops (USCT) infantry. The USCT was a segregated branch of the Union Army to be led in combat by white officers. Several of Oberlin’s black residents would enlist in these regiments. Carter was mustered into the 27th USCT in January, 1864. [2]

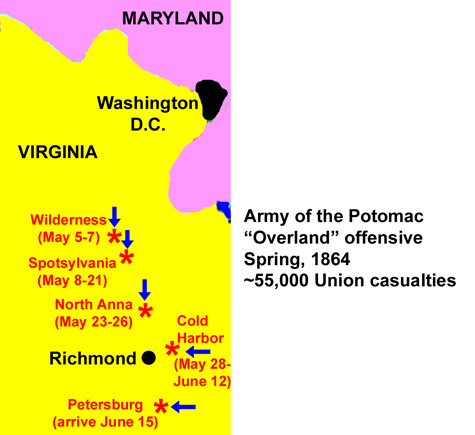

After completing basic training, the 27th USCT was attached to the Army of the Potomac, led by Generals George Meade and Ulysses S. Grant. The Army of the Potomac would spend the Spring of 1864 locked in a death grip with the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee. As the two armies slugged it out across northern Virginia, closing in on the Confederate capitol of Richmond, much of the combat developed into grueling trench warfare, ultimately culminating at the city of Petersburg, where Lee’s troops dug in once again.

Up to this point virtually all the fighting had been done by white troops. Many Union officers didn’t trust black troops in combat. Others were concerned about Confederate threats to enslave captured black soldiers or execute them for “servile insurrection”. Events at Fort Pillow in Tennessee in April seemed to confirm these threats, with reports of hundreds of black soldiers being executed by Confederates after they surrendered. And so Private Carter and the black troops of the Army of the Potomac were assigned to guarding wagon trains behind the lines.

But now General Ambrose Burnside, commander of the IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac, had two novel ideas to break the stalemate. He would dig a mine beneath the Confederate entrenchments at Petersburg, load it with tons of black powder, and ignite it, blasting an opening in the Rebel lines. And instead of sending his weary, shell-shocked white troops to exploit the breach, he would send his black troops, whose fighting qualities he believed in, and who were “wrought up to a fever heat of zeal” to prove themselves in battle and avenge Fort Pillow. [3]

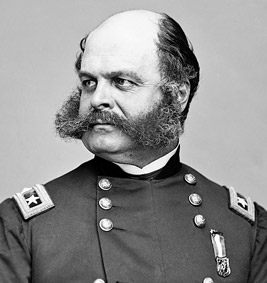

Major General Ambrose Burnside

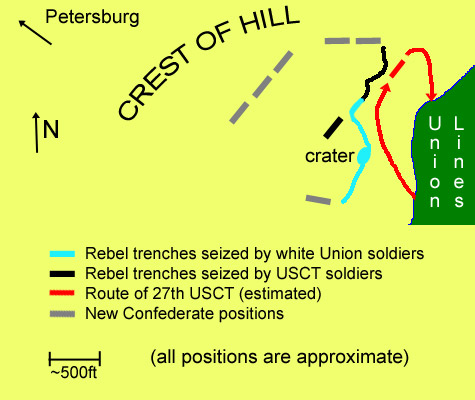

The section of the Confederate entrenchments to be blown up was on the side of a hill only a few hundred feet west of the Union lines. General Burnside’s lead USCT troops repeatedly rehearsed an “imaginary advance” through the breach created by the explosion to stake a position at the crest of the hill, giving them a commanding position on the battlefield that the white troops could then come in and widen. But at the last minute this part of Burnside’s plan was changed by Generals Meade and Grant, who felt that putting untested black troops into such a potentially precarious position could have political ramifications. Instead the lead role was given to a white division led by General James Ledlie, reputed to be incompetent and a battlefield drunkard. Two other white divisions would follow his, and the black division, which included the 27th USCT, would bring up the rear. The attack was scheduled to start before daybreak the following day, July 30, 1864. [4]

[Warning – the remaining text contains graphic violence and racist language in its original, historic context]

Perry Carter and the men of the USCT were awakened at 2:00 on the morning of the 30th and lined up behind the three white divisions that would lead the assault. The 27th USCT lined up with three black regiments ahead of it, about 350 yards from where the mine was expected to explode. When the mine finally blew at 4:44 A.M., one of the USCT officers described it as follows:

“the explosion… was preceded by one or two slight motions of the earth, something like a heavy swell at sea, a dull rumbling sound (not loud) like distant thunder, then the uplifting of earth like an island which seemed suspended in the air and held as by invisible hands, supported as it were by gigantic columns of smoke and flame; all this but for a moment, then like the vomiting of a volcano, it burst into innumerable fragments and fell a confused inextricable mass of earth, muskets, cannon, men; an awful debris.” [5]

After a brief delay, Ledlie’s men started moving across an open expanse of land called “no man’s land”, towards the Rebel lines that had just been destroyed. Here they found an enormous crater, about 120 by 50 feet, and 25 feet deep. Operating under the orders of General Ledlie (who remained behind the lines at a bombproof shelter throughout the action), the men clambered into the crater.

The walls of the crater were very steep, and the men soon learned that getting in was a whole lot easier than getting out – especially when the Confederates recovered enough to begin firing at them. Some of the men began an attempt to break out to the north and south, where the crater adjoined the existing Confederate trenches, but the going was made rough by the upheaved terrain, the confused labyrinth of Confederate entrenchments, and the resistance of those Rebel soldiers who had survived the blast. And none of this was moving towards the true objective, which was the crest of the hill to the west of the crater.

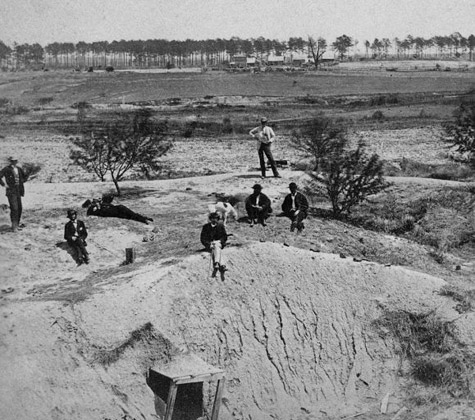

The Crater (pictured shortly after the war)

While the troops within the crater struggled to get out, more and more troops were sent in to join them, where according to one General, they were “without any organization; just one mass of human beings seeking shelter.” To make matters worse, the Confederates had known about the mining and had planned for just such an occurrence. The result being that the Union soldiers were now trapped in the crater and a few dozen yards of Confederate entrenchments on either side of it, while Confederate artillery fire rained upon them and Confederate infantry to their west blocked any attempts to seize the crest of the hill. [6]

In the midst of this chaos, General Meade, out of touch with battlefield conditions, ordered General Burnside to send in his black troops as well, adding their numbers to the chaos and confusion. And even though officers on the field tried desperately to revoke the order and send them back, the black troops “went in cheering as though they didn’t mind it.” [7]

Yet now, remarkably, something actually went right for the Union side. Perry Carter and his comrades were exposed to “a most deadly cross-fire from both flanks” as they made their way through no-man’s land. Reaching the crater, Colonel Seymour Hall “realized that to pass through the crater as ordered would be impossible.” So they bypassed the crater on the right, maneuvered their way around the chunks of earth and immobilized white troops, and scrambled through the Confederate trenches. Under the inspired leadership of Colonel Hall and Colonel Delavan Bates, the lead USCT regiments attacked Confederate entrenchments north of the crater with “a determination to do or die.” [8]

Literally. Remembering Fort Pillow, they were “not expecting any quarter, nor intending to give any.” The hand-to-hand combat in the trenches was among the most brutal in the Civil War, where “men would drive the bayonet into one man, pull it out, turn the butt and knock the brains out of another.” The acrimony between the Confederate and black soldiers made it especially savage, with Colonel Bates attesting “it was the only battle I was ever in where it appeared to be just pure enjoyment to kill an opponent.” Some Confederates yelled, “Kill the damn niggers!” as the black soldiers “charged as though they were going to eat us up alive, yelling ‘no quarters [sic], remember Fort Pillow.'” One USCT officer reported intervening to save a “batch” of Rebel prisoners from a “group of men of my own company, who in two minutes would have bayoneted the last poor devil of them.” Another white soldier reported seeing a black soldier bayonet a Rebel prisoner to death “in an agony of frenzy.” [9]

But in the end, the lead USCT regiments took about 200 Rebel prisoners and captured about 200 yards of enemy entrenchments. The trailing USCT regiments faced a different situation, however, having been cut off from the lead regiments during the advance around the crater. So although Perry Carter and the 27th USCT missed the hand-to-hand combat in the trenches, they were left “very much exposed to the fire of the enemy [for] at least an hour.” [10]

Yet finally, four hours into the battle, a serious effort was made to advance to the crest of the hill. A great deal of heroism was displayed as the USCT officers rallied and reorganized their lead troops for the advance, all the while under heavy fire. The men “formed properly. There was no flinching on their part. They came to the shoulder touch like true soldiers, as ready to face the enemy and meet death on the field as the bravest and best soldiers that ever lived.” [11]

But it was too late. Had it been done at the beginning of the battle as originally planned, it might have succeeded. Four hours into the battle, however, the Confederates had succeeded in bringing in reinforcements from up to two miles away. One after another USCT officer was gunned down as he rallied his men and tried to form a battle line, and now a line of fresh Rebel troops rose out of the ravine ahead with bayonets fixed and advanced on the leaderless USCT troops. With that the USCT troops did what virtually all rookie Civil War troops did when their command broke down and they were faced by an enemy onslaught – in the words of one of Ledlie’s staff officers, “they ran like sheep.” [12]

Some of them fled as far as the crater and took cover there. Others fled all the way back to the Union lines. White soldiers fled too, and now the 27th USCT found itself in an untenable situation, “exposed to a terrific flank fire, losing in numbers rapidly and in danger of being cut off.” And so its commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles J. Wright, gave the order “to retire through the ravine on the right”. The withdrawal of the 27th was no cakewalk, however. “While on retreat under fire of the Rebel Artillery, Perry Carter was struck on his left shoulder by some missile, knocking him down and making an ugly wound. His comrades assisted him off the field.” Among those comrades was Oberlin’s Simpson Younger. [13]

Meanwhile, back at the front lines, the situation was atrocious. Union soldiers had been driven back into the crater where they were “about as much use there as so many men at the bottom of a well.” Hundreds of men crammed in a small area, under the scorching sun on a 100+ degree day, among dead bodies and body parts and pools of blood, wounded men screaming and moaning, the stench intolerable, water virtually unavailable, and Confederate shells falling among them. The white soldiers who had been fighting all morning were beyond the limits of endurance; most now “sat down, facing inwards, and neither threats nor entreaties could get them up into line again.” According to Lieutenant Bowley of the 30th USCT, “from noon until the capture of the Crater, two hours later, the firing was kept up almost wholly by the colored troops.” [14]

When Confederate troops finally broke into the crater, there was nothing for the Union troops to do but surrender. But that didn’t stop the carnage. Many black troops who tried to surrender were told by their captives, “No quarter this morning, no quarter now.” Confederate Major John Haskell explained later that “our men, who were always made wild by having negroes sent against them… were utterly frenzied with rage. Nothing in the war could have exceeded the horrors that followed. No quarter was given, and for what seemed a long time, fearful butchery was carried on.” Most shamefully of all, some white Union soldiers participated in the slaughter of their black comrades-in-arms, both on account of their own racial hatred and to curry favor with their Confederate captors. [15]

The Battle of the Crater was a disaster for the Union. General Grant called it “the saddest affair I have witnessed in the war,” and confessed that if they had gone in with the “colored division in front”, he believed “it would have been a success.” But instead it was a sad initiation into combat for the 27th USCT. Mismanagement by the Union high command led them to be “rushed into the jaws of death with no prospect of success.” Four of its officers were killed or mortally wounded, and Lieutenant Colonel Wright was hit twice. Untold number of other soldiers were also injured, including four Oberlinites. [16]

For Perry Carter it was a long, painful road to recovery. His wound was sewed up and treated with adhesive plaster, but it would be two months before he could return to active duty. That he did though, and served honorably to see the surrender of Confederate forces in 1865. In September, 1865 he was recommended for promotion to Corporal, but his regiment was mustered out of service before the promotion could go through. [17]

Carter returned to Oberlin where he remained under medical treatment for his injury for the rest of his life. Unable to lift his arm above his head or lift anything heavy, he was no longer able to work as a drayman. Instead he was “compelled to do such manual labor as I was able to do to support my family, chiefly teaming and lighter kinds.” But none of that stopped him from playing an active role in local Republican politics and the Rust M.E. Church, or from being a popular community member and party host. [18]

Perry Carter died in 1892, just two years after his big party, and was buried in the Soldier’s Rest section of Westwood Cemetery. (Oberlinites William Broadwell, Richard Evans and Thomas Hartwell, who were also injured at the battle, are buried at Westwood as well.) [19]

(In my next blog, we’ll see how the 5th USCT had a much more successful baptism under fire, but with tragic results for Oberlin.)

SOURCES CONSULTED:

Earl J. Hess, Into the Crater: The Mine Attack at Petersburg

Richard Slotkin, No Quarter: The Battle of the Crater, 1864

Oberlin College Archives (abbrev. “O.C.A.” below), RG 30/151, Series I, Subseries 1, “William E. Bigglestone Papers; Files Relating to They Stopped in Oberlin; Civil War Military Records”

George Washington Williams, A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion

James M. Guthrie, Campfires of the Afro-American

“A Social Event”, Oberlin Weekly News, September 18, 1890, p. 3

H. Seymour Hall, “Mine Run to Petersburg”, War Talks in Kansas

Delevan Bates, “A Day with the Colored Troops”, The National Tribune, January 30, 1908, p. 6

Official Records of the Rebellion (abbrev. “O.R.” below), Series 1, vol 40, Part 1 (Richmond, Petersburg)

William E. Bigglestone, They Stopped in Oberlin

Ulysses S. Grant, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: November 16, 1864-February 20, 1865

John F. Schmutz, The Battle of the Crater: A Complete History

Oberlin News, July 7, 1892, p. 5

Grace Hammond, Elizabeth Harrison and Jennifer Ni, “Rust United Methodist Church: A Brief History”

“Westwood Cemetery Inventory”, Oberlin Heritage Center

“Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database”, National Park Service

George S. Bernard, War Talks of Confederate Veterans

Oliver Christian Bosbyshell, The 48th in the War

Andrew Carroll, War Letters: Extraordinary Correspondence from American Wars

Jefferson Davis, “Proclamation by the Confederate President”, GENERAL ORDERS, No. 111. , December 24, 1862

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Oberlin News; “A Social Event”

[2] Oberlin News; Civil War Military Records (“Carter, Perry” file), O.C.A.

[3] Hess, p. 55

[4] Hess, p. 55; Slotkin, pp. 96-100

[5] Hall, p. 235

[6] Guthrie, p. 523

[7] Guthrie, p. 529

[8] Hall, p. 223; Slotkin, p. 236

[9] Hess, pp. 128-129, 161; Bates; Slotkin, p. 236; Hall, p. 238

[10] O.R., pp. 596-597

[11] Hess, p. 141

[12] Hess, p. 217

[13] O.R., pp. 596-597; Affidavit (Simpson Younger, June 5, 1886), “Carter, Perry” file, O.C.A.

[14] Hess, pp. 185, 181; Slotkin, p. 277

[15] Slotkin, pp. 290-291

[16] O.R. p.17; Grant, p. 142; Guthrie, p. 529; Schmutz, pp. 221, 362

[17] Civil War Military Records (“Carter, Perry” file), O.C.A.

[18] Affidavit (Perry Carter, Dec. 10, 1881), “Carter, Perry” file, O.C.A.; Hammond

[19] Civil War Military Records (“Broadwell, William”, “Evans, Richard”, “Hartwell, Thomas” files), O.C.A.; “Westwood Cemetery”