by Ron Gorman, Oberlin Heritage Center volunteer docent

November 1864 – 150 years ago this month – saw a curious spectacle in the American Civil War. After Union General William Sherman captured the city of Atlanta from Confederate General John Bell Hood, both armies turned and headed away from each other, with the goal of bringing the hard hand of war to their opponent’s civilian infrastructure. Sherman headed southeast on his infamous March to the Sea, intending to “make Georgia howl”. Hood turned north on what could have been just as infamous a march, perhaps even inducing some howling north of the Ohio River. But where Sherman’s march was a success, Hood’s march failed to even make it out of Tennessee. An Oberlin man would earn the Medal of Honor and an interesting keepsake for the part he played in stopping him.

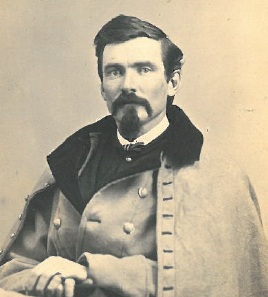

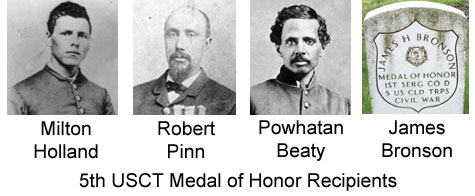

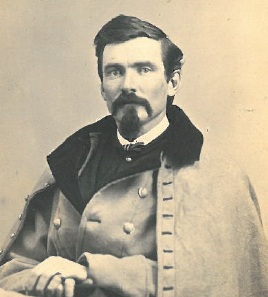

John Whedon Steele

(courtesy Oberlin College Archives [1])

His name was John Whedon Steele, and he missed by only a few miles becoming one of the first citizens born in Oberlin. Instead he was born near Akron as his parents migrated en route to Oberlin from New York in 1835. His father, Dr. Alexander Steele, would become Oberlin’s first full-time physician. His younger brother, George, would become an Oberlin College professor and co-founder of the music conservatory. But it appears that John always had somewhat of a reputation as a renegade (well… by early Oberlin standards, that is). Nevertheless he attended Oberlin College, got his law degree in Michigan, and returned to Oberlin just before the start of the Civil War. [2]

At the outbreak of war, Steele joined with Alonzo Pease (artist, Underground Railroad operative, and nephew of Oberlin’s first settlers) to recruit a company of infantry. The company would eventually muster into service as Company H of the 41st Ohio Volunteer Infantry, with Pease as Captain and Steele as First Lieutenant. They soon found themselves in the “western theater” of operations, ultimately making their way to Tennessee, and Steele was promoted and transferred to Captain of Company E. According to the Lorain County News, this company was “made up of roystering blades from Cleveland and other cities which have made their previous commanders much trouble. John [Steele], however, suits them to a dot and they are fast working into a state of superior discipline.” Steele would lead this company in a “gallantly and successfully” executed charge against a rebel battery at the first bloodbath battle of the war, the Battle of Shiloh, in April, 1862. [3]

It wouldn’t be long, however, before Steele was again promoted and transferred, this time to Major, ultimately serving as aide-de-camp on the staff of General David S. Stanley’s 4th Corps. Although we sometimes tend to think of staff officers as holding cushy desk jobs, nothing could be further from the truth for many of them. In the Civil War, staff officers were often in the thick of battle, relaying orders from their superiors to the troops on the field, directing troop movements, and coordinating attacks. Such appears to be the case with Major Steele. He participated in two more epic bloodbaths, at Stones River and Chickamauga, before joining in General Sherman’s four month campaign to capture Atlanta in the summer of 1864. [4]

After Sherman took that city, the two armies engaged in two months of cat-and-mouse warfare in northern Georgia and Alabama in which they failed to come to a general engagement. Finally they turned and went their separate ways, in General Stanley’s words, “like two school boys… each saying ‘Well I cannot whip you but I can kick over your bread basket.'” But before Sherman turned east to kick over Georgia’s bread basket, he detached two corps under General John Schofield, with orders to join forces with Union General George Thomas in Nashville and stop Hood’s advance. General Stanley’s 4th Corps, with Major Steele as aide-de-camp, was included in Schofield’s detachment. [5]

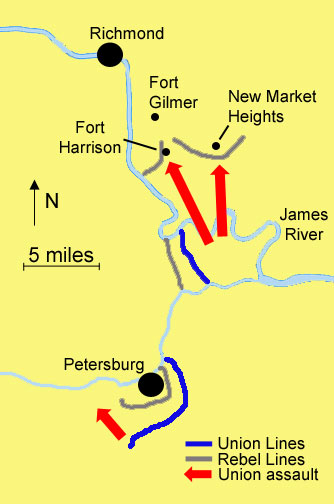

Hood now knew that his northward journey would be a difficult one, but being one of the most aggressive commanders in the war, he was not deterred. His army was larger than either Thomas’ or Schofield’s detachments, and he believed that if he could isolate them and bring them to battle independently, he could destroy them in kind, then turn his attention to Ohio’s “bread basket”, or perhaps come to the rescue of Robert E. Lee’s besieged army in Virginia (see my Battle of New Market Heights blog).

(Troop movements and positions are approximated and simplified, for clarity’s sake)

Hood’s first victim was to be General Schofield, who had a vulnerable supply line leading back to the main Union depot at Nashville. Hood devised a plan whereby he would march his army around Schofield’s flank to Spring Hill, Tennessee, where he could cut that supply line and isolate Schofield from Thomas before they had a chance to link up.

The movement was accomplished brilliantly, but when Hood’s troops arrived at Spring Hill on November 29, they were met by a division of General Stanley’s 4th Corps, which had been sent in advance with Schofield’s wagon train. It’s not known what part Major Steele played in the fierce fighting that accompanied this part of the battle, but his comrades held their ground, and the rebels retired at nightfall.

They didn’t retire far, however. In fact they went into bivouac right alongside the turnpike that General Schofield’s troops would have to travel to get to Nashville. It was an “extremely perilous” situation for the federals, and Schofield decided he needed to get out of it – quick. So he ordered a night march in which his troops would tramp as quietly as possible up the turnpike past the resting Confederates. [6]

Amazingly, it worked. Well, almost. Schofield’s infantry marched cleanly out of the trap. But bringing up the rear was the slow, cumbersome wagon train – 800 wagons and caissons carrying the food, ammunition, medicines, and artillery needed to support Schofield’s infantry. With most of the infantry already gone, the train creaked and groaned up the narrow turnpike, past the campfires of the rebel troops, escorted only by a scant guard. It was, in General Stanley’s words, “like treading upon the thin crust covering a smouldering volcano.” [7]

Then at about 3:00 A.M. the volcano blew. Several regiments of Confederate cavalry launched a flank attack against the head of the helpless wagon train. Years later, General Stanley, who was “thrown into despair” by the news, described what happened next: [8]

“My two most vigilant staff officers, General [then Colonel] Fullerton and Colonel [then Major] Steele … were near the point attacked which was about four miles from Spring Hill. Instantly they took measures to repel the attack. They found our headquarter’s guard… This company was about thirty-five strong and commanded by a gallant young officer, Captain Scott. Using this as a nucleus, these gallant officers picked up from train guards, headquarter’s guards, anyone carrying a gun, a little body of men, marched up to point blank range, gave the rebels a volley which cleared the road, and very soon our big train moved on again.” [9]

Interestingly, in Stanley’s original report to headquarters, he gave all the credit to Major Steele, with no mention of Fullerton or Scott. But by all accounts less than five percent of the Union wagons were destroyed; the rest were saved by the makeshift strike force, whose boldness apparently deceived the rebels into believing the train guard was much larger than it really was. [10]

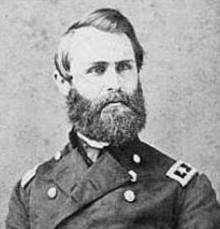

At daybreak, Hood was furious to learn that Schofield had slipped out of his trap. Now that his best opportunity to prevent a link-up between Schofield and Thomas was lost, he would throw his troops headlong into Schofield’s command in desperation. That reckless assault would occur late that afternoon, November 30th, fifteen miles north of Spring Hill, at Franklin, against stout Union defenses prepared largely by another Oberlin alumnus, Major General Jacob Cox of the 23rd Corps, and supplied in part by the wagon train that had been saved by Steele’s improvised force that morning. The result was arguably the most devastating defeat suffered by the Confederate army in the entire war. Six Confederate generals were mortally wounded that day. Only one Union general was wounded, and that was General Stanley, who was struck by a bullet in the neck as he took the field to help lead a countercharge and close a dangerous breach that had opened in his lines. Major Steele was reported to be with him; that is, until he was knocked off his horse by a rebel Minié ball (a large caliber rifled bullet notorious for its bone-shattering effects) that passed through his breast pocket. But Hood was repulsed, and that night Schofield slipped away again, ultimately to hook up with General Thomas at Nashville, where two weeks later they virtually destroyed what was left of Hood’s army. Ohio was saved from invasion. [11]

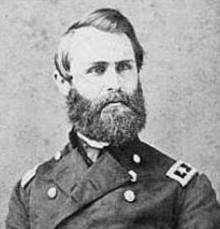

Jacob Dolson Cox [12]

Meanwhile, Stanley and Steele were furloughed to convalesce from their wounds. Steele would tell the Oberlin townsfolk how his life had been saved by the contents of his breast pocket, which absorbed the impact of the Minié ball that struck him down. But this wasn’t the classic narrative of the devout war hero saved by a bullet-stopping Bible. Instead, Steele liked to tell how he was hit “in my euchre deck”. (One can only wonder whether the theologians of Oberlin shook their heads in disappointment over the card-playing, cigar-smoking, renegade hero!) [13]

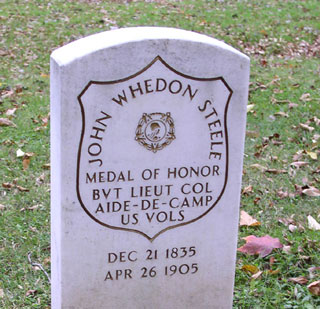

Steele recovered and returned to action, this time in Texas, to fight the last major Confederate hold-out, General Edmund Kirby Smith. He received one more promotion, to brevet Lieutenant Colonel, before he was mustered out of service in 1866.

But his life of service was only just beginning. He returned to Oberlin and became active in all aspects of community life and politics. He served as Lorain County Probate Judge and for many years as Oberlin’s Postmaster. At a community meeting in February, 1866, he delivered a speech and joined in passing a set of resolutions supporting Congress in its growing rift with President Andrew Johnson over Reconstruction policy. Among the resolutions passed was one exhorting Congress “to give the control of the nation to its loyal inhabitants, and full protection to the freed men in the exercises of all rights and privileges we claim for ourselves.” [14]

He was a staunch advocate of a reliable, safe community water supply, and played a crucial role in bringing it to fruition. He also worked tirelessly for other modern improvements, as well as community beautification. “We’ve got to keep moving,” he told a community meeting. “No psychology or theology will make a person who is accustomed to a marble lavatory, satisfied with a wash bowl on a stump. Self-inflicted torture is out of date… The world moves and we have to move with it. In fact we ought to move a little ahead of it.” [15]

He firmly believed that citizens ought to “so arrange our private affairs as not to close the door against our public duties.” And practicing what he preached, he accepted an appointment as a trustee of the County Children’s Home in Oberlin. In the words of Oberlin College Professor Azariah S. Root, “One had only to see the Judge as he was about the place and witness the affectionate attitude of the children toward him, to realize how much of genuine, loving service he was giving to the enterprise…” [16]

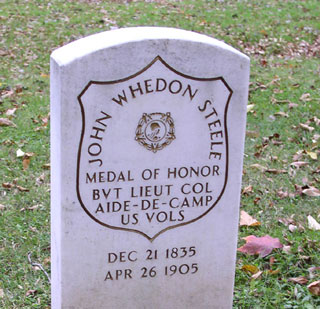

In 1897 he was awarded the Medal of Honor for “saving the train” at the Battle of Spring Hill 33 years earlier, and President William McKinley, a fellow Ohio Republican Civil War veteran, invited him to the White House. (Interestingly, Steele’s commanding officer, General Stanley, received the Medal of Honor four years earlier for the counterattack he “gallantly led” at the Battle of Franklin in which he and Steele were wounded.)

Steele’s final public service was one of particular honor and responsibility. He was selected to distribute the funds that had been donated by Andrew Carnegie to students and residents of Oberlin who had been financially devastated by the failure of the Citizens Bank in the wake of the Cassie Chadwick scandal. According to Oberlin College President Henry Churchill King, “no one could be associated with him in that work, and not recognize the great pains with which he went into the multitudes of cases, following them out with insight and tact and sympathy, carrying often their burden as though it were an individual burden of his own.” [17]

It is noteworthy that Steele, a non-religious man, should gain such a reputation for “uncompromising honesty” and trustworthiness in the devoutly pious community of early Oberlin. He did in time, however, confess to telling one little white lie. In an 1886 interview with a Chicago newspaper, Steele divulged that the bullet-stopping contents of his pocket on the battlefield that distant day was not a euchre deck after all. But neither was it a New Testament or an Old Testament. Instead it was a leather-bound memorandum book, which he kept and passed on to his family, bullet hole and all. When asked why he had told the “staid but patriotic professors at Oberlin” that it was a euchre deck, Steele explained: “You see, I was afraid they would distort my memorandum book into a Testament, and make a text of the incident, and I had to do a little hedging to keep myself out of the pulpit.” [18]

On April 26, 1905 the pulpit caught up with Colonel Steele nonetheless, when at the age of 69 he died of a heart ailment. The Oberlin News devoted its entire front page and much of its second page to an obituary and the transcripts of three eulogies delivered at his funeral service at First Church. One of the eulogists was Oberlin College President King, whose words I close with:

“…In his death Oberlin loses one of her most individual links with her past, and one of her most interesting and important citizens. Thinking himself, doubtless, sometimes out of sympathy with much in Oberlin, he nevertheless showed a persistent and an almost unmatched devotion to her interests, both in the defense of her reputation and in care for her practical interests…

We are coming to understand now what was not so clear in the days of his young manhood, that we cannot require the same kind of response from widely different temperaments.

… but his close friends learned to see that a sometimes brusque manner was the shield of a marked sensitiveness and a rare tenderness that yet could not be wholly hidden. And those did not know him who had not seen in him that delicate courtesy that seems often to belong to the true soldier – a courtesy that was more than courtliness, full of genuine human feeling, and free from all affectation and every trace of condescension. He was a rare friend and a rare public servant.” [19]

John Whedon Steele is buried in Westwood Cemetery, Section R, where his grave is a stop on the Oberlin Heritage Center’s “Radicals and Reformers” history walk.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

Wilbur H. Phillips, Oberlin Colony: The Story of a Century

“Another Honored Citizen Gone”, Oberlin News, May 2, 1905, pp. 1-2

David S. Stanley, Personal Memoirs of Major-General D. S. Stanley

“John W. Steele Ex ’60”, Oberlin Alumni Magazine, Vol 1, pp. 238-239

“Col. J. W. Steele”, The Elyria Republican, July 29, 1886

John K. Shellenberger, The Battle of Spring Hill, Tennessee

Dennis W. Belcher, General David S. Stanley, USA: A Civil War Biography

Jamie Gillum, Stephen M. Hood, Twenty-five Hours to Tragedy: The Battle of Spring Hill

“The 41st O.V.”, Lorain County News, April 16, 1862, p. 2

“The 41st O.V. before, at and after the Battle of Pittsburg Landing”, Lorain County News, April 30, 1862, p. 2

“The Voice of Oberlin, Its Words for the Crisis”, Lorain County News, March 7, 1866, p. 3

Official Records of the Rebellion (abbrev. “O.R.” below)

“Promoted”, Lorain County News, February 29, 1862, p. 2

George Frederick Wright, A Standard History of Lorain County, Ohio

Oberlin College Archives, “Steele, John Whedon 1851-1858” student file, RG 28, Series 1, Sub-series 1, Box 241

“41st Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry (1861-1865)“, Ohio Civil War Central

“Jacob Dolson Cox (1828-1900)“, The North Carolina Civil War Experience

Robert Samuel Fletcher, A history of Oberlin College: from its foundation through the Civil War, Volume 1

General Catalogue of Oberlin College, 1833 [-] 1908, Oberlin College Archives, p. 1582

“Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database”, National Park Service

“Pension applications for service in the US Army between 1861 and 1900”, National Archives.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] “Steele, John Whedon 1851-1858” student (alumnus) file, Box 241

[2] Phillips, pp. 220, 234

[3] “Promoted”, “The 41st O.V.”; “The 41st O.V. before…”; O.R. Series I, Volume X, Part 1, p. 324

[4] “Another Honored Citizen Gone”

[5] Stanley, pp. 196-197

[6] O.R. Series 1, Vol 45, Part 1, p. 1138

[7] Stanley, p. 204

[8] O.R. Series 1, Vol 45, Part 1, p. 115

[9] Stanley, p. 205

[10] O.R. Series 1, Vol 45, Part 1, p. 115

[11] ibid.; Belcher, p. 213; “Col. J. W. Steele”; Phillips, pp. 223-224

[12] “Jacob Dolson Cox (1828-1900)”

[13] “Col. J.W. Steele”; Phillips, pp. 224, 239

[14] “The Voice of Oberlin”

[15] Phillips, pp. 153, 233; “Another Honored Citizen Gone”

[16] Phillips, p. 234; Wright, p. 183; “Another Honored Citizen Gone”

[17] “Another Honored Citizen Gone”

[18] “Another Honored Citizen Gone”; Phillips, pp. 224, 234; “Col. J.W. Steele”

[19] “Another Honored Citizen Gone”

![]() icons are actually links to sound files so that you can hear our Oral History interviewees tell their own stories!*

icons are actually links to sound files so that you can hear our Oral History interviewees tell their own stories!*–Magdalene Cox (as interviewed by Betty Thomas), November 24, 1982