“There’s Mischief in this Man”: William Mallory and the Oberlin Collegiate Experience

by Jen Graham, Ohio History Service Corps member at the Oberlin Heritage Center

As a historian, I’ve fallen in love with letters. There is a striking liminality in reading someone else’s mail. It’s as if, by unfolding the delicate creases of yellowed paper and losing yourself in a sea of cursive, you unfold time as well. With each new reading, experiences of the past come alive in the present. People long since dead become children again. Couples who grew old together find themselves back in the adorably awkward throws of courtship. Every casual misspelling, every witty retort, tells a story, and what began as a research topic ends up feeling more like a close friend.

My most recent foray into historical familiarity has been with a man named William Garfield Mallory (1880-1918). William Mallory was born in Chautauqua County, New York, and entered the Oberlin Senior Academy in 1899. He graduated from Oberlin with an A.B. in 1905 and a Masters in Physics in 1907. In 1909, he married Mary K. Pope of Oberlin. Afterwards, he moved back to New York to study physics at Cornell and graduated with his Ph.D. in Physics in 1918. He then accepted a teaching position in the Physics Department at Oberlin College, but, unfortunately, died only a few months later of influenza.

I first met William Mallory when Prue Richards, the Oberlin Heritage Center’s collections assistant, invited me to help her organize the letters in a writing box donated by his descendants, Marianne Caldwell and William Dickerman. Also donated with the box were a sled, a jacket, a portable stove, and myriad family photos. At first I was just taking the letters out of their envelopes, laying them flat, and placing each one in an archival plastic sleeve. I wasn’t reading them or transcribing them; I was just preparing them for storage in the collections. Well, curiosity got the best of me.

What piqued my interest was not the overall story of his life. Those were just facts to me—information to help contextualize the task at hand—until I noticed a return address on a letter. That’s when I had my first moment with William Mallory. The letter was a note from Mallory to his cousin, Edith, penned while he was a student at Oberlin College. The address was 115 E. College St., which I recognized because, just over a century after that letter was written, I had lived right across the street in Tank Hall.

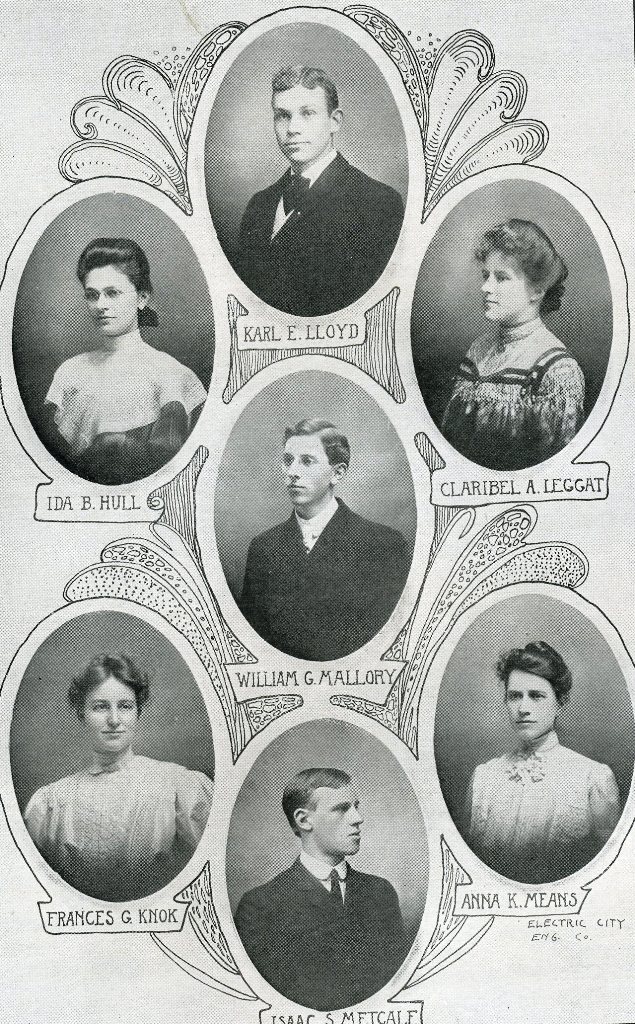

Spatially, our college experiences were beginning to merge. I had to get closer. I devoured that letter and the others with it. I followed Mallory through the Oberlin College “Hi-O-Hi” yearbooks like a lovesick teenager. I found him on the track team in 1902. I found him included among the stony-faced members of the Phi Delta literary society in 1905. I even found his graduation picture and quote. Surrounded by “cheery-voiced” men and women with “an abhorrence of sin,” our straight-backed, intellectual William Mallory was described rather differently. Five words laid it all on the table: “There’s mischief in this man.”

And it must have been true, because his accomplice in the prank described below, Merton Chamberlain, was accompanied by the quote, “A kinder gentleman treads not the earth.”

Into our freshman’s bed there strayed a tin can, and a spool of thread. Sometime after going to bed he was aroused, lighted a match and began looking about for “the devil,” as he said. Mr. Luckey came to the stair door to see what was the matter. My partner and I then jumped into bed, and let the fun go on.

— William Mallory to his grandparents February 17, 1905

Not simply a prankster, in another letter, Mallory casually poked fun at his roommate Laverne’s facial hair, writing:

“He is growing a mustache (comprised of 8 hairs, the color of road dust, and a stick of wax on each end.) He must spend 15 minutes daily cultivating it. What a waste of time!”

— William Mallory to his cousin Edith, 1900

William Mallory had a dry wit, but, like most Oberlin students, he worked hard. While he took a particular interest in the sciences, he also studied German, Latin, geometry, botany, history, and religion. Even reading his schedule was exhausting. He often rose before dawn to begin his studies, and worked or attended literary society meetings until 9:30 or 10:00 at night, only to repeat the process again the next day. He had laboratory sessions to attend, and various odd jobs in town to earn money for the rooms he rented. He joined a basketball team (“the best team in the college”) with some boys in his class and attended church four times on Sundays. Surprisingly, he somehow found time to sleep six to nine hours every night!

My favorite passage about his schoolwork concerned a history course Mallory took from Mrs. Adelia Field Johnston. Mrs. Johnston was first a graduate of Oberlin’s literary course for women in 1856. She then accepted a position as principal of the Oberlin Ladies’ Department. In 1878, Johnston was appointed the first female professor in Oberlin, and she later became the first woman on the Oberlin College Board of Trustees. Of her class Mallory writes:

History is my most enjoyable course now. Mrs. Johnston gives us outlines of her lectures, then we listen, and write them out from memory. Because it compels attention, as well as because the course itself is valuable, I like it.

— William Mallory to Edith (undated)

A similar highlight in the collection of William Mallory’s letters (and in any account of Oberlin’s past) has to do with girls. In describing Oberlin to his cousin Edith in 1900, he lamented that “the rules are very strict about fooling with the girls. Cannot stay at the boarding house after 7 P.M. Must not speak to them after meals on Sundays, etc. etc.” Even still, despite his busy schedule and all the restrictions, he managed to find time to visit the ladies once a week. By the end of that first year, he already had favorites. As students were leaving for spring break, he wrote to William Wood, his grandfather: “There are only two girls left. But as they are the two best ones of the lot, I could stand it, if the other boys did not think so too.”

He didn’t just talk about women, though. In multiple letters, Mallory mentioned speaking with people of different races. Whether it was the African-American student who won an oratory contest in the Academy, or John Williams who spoke at a party of the treatment of African-Americans in the southern United States, or two Chinese boys who had survived the Boxer Rebellion, these encounters with such a diverse community expanded William Mallory’s horizons and opened his mind to new experiences.

William Mallory also encountered all the diversity of weather northeastern Ohio has to offer. His meteorological observations were a delight to read. I remember last October when residual storms from Hurricane Sandy blew off part of the roof of the Science Center on campus. Once, when driving into Cleveland, I experienced four different weather patterns on my commute. It wasn’t so different for William Mallory in the early 20th century.

Yesterday was a beautiful day, but it snowed hard in the evening. The weather changes very quickly.

— William Mallory to his grandfather April 4 1900Once in a while we have a day with blue sky, but twice in a while we have dark, rainy days…The wind blew down the flag pole, on the campus, and took off a good many large limbs, and more small ones. But the next morning the sun came up clear, there was a little breeze from the north, and we thought we had a promise of fair weather, but now rubber boots are the proper things to wear again.

–William Mallory to his grandparents, 1903

The more I got to know William Mallory, the less I was prepared to stumble across the last two letters from Oberlin, dated October 6, 1918. One was from William Mallory to his mother in New York, wishing her a happy birthday, and describing a little of his new teaching job at Oberlin. He was busy because the laboratory was not in very good shape. There were a surprising number of young women in his classes, he declared, though “not all of them give early promise of being great scholars of Physics.” He wondered if some of the young ladies might not “drop out soon.”

The other letter was from his ten-year-old daughter, Stella Irene, to her grandmother, also wishing her a happy birthday. In the letter, little Stella Irene wrote in the large, careful print of a child about her school, her younger brother, Robert, a pet chicken, and her father’s health. “Dada is much better,” she said. “He is so he can get up and around some. A lot better than when we came.”

Sadly, not long after these letters were posted, William Mallory was dead. He was 38 years old. Out of respect for his memory, classes at Oberlin College were cancelled on October 21, 1918 for his funeral. He was survived by his wife, Mary Pope Mallory, and his two children, Stella Irene, age 10, and Robert, age 5.

William Mallory with his wife, Mary, daughter, Stella Irene, and son, Robert

(from the Oberlin Heritage Center collection)

William Mallory’s letters are important, not simply for their sentimental value. They tell a story of a time in Oberlin when strict rules for female students were beginning to loosen, when people of all races came together to talk about their experiences, and when World War I took control of the community’s routine. The letters, photographs, and objects donated by Marianne Caldwell and William Dickerman add important dimension, not only to the name William Mallory, but to the already multi-faceted story of Oberlin as well.